Introduction to the history of medieval

boroughs

Introduction to the history of medieval

boroughs Introduction to the history of medieval

boroughs

Introduction to the history of medieval

boroughs

| Origins: planned / planted towns |

When we study urban development, we should be wary of thinking too much in terms of an organic process, even though one phase of development of a settlement frequently seems a natural continuation of a previous phase. For instance, the crossing point of two highways was a natural meeting-place where trade might occur and, if it did so with regularity, the spot might become a marketplace which attracted settlement; or the foundation of an abbey might be followed by the clustering, outside the abbey gates, of houses of those providing services or selling goods to the monks (e.g. Battle); or again, a ford across a river might attract settlement, expansion of which might follow a ridge of higher ground paralleling the river and/or the courses of streams leading off the river. On the other hand, although a certain amount of spontaneity or informal decision-making must have been played a role in the developmental history of many urban centres, towns did not grow themselves: they were to a large degree the product of planning to respond to human needs. Putting aside the fact that much urban development was accomplished before record-keeping became a habit in towns or at seigneurial levels, we should not expect the process necessarily to involve documented long-range plans carried out in pre-determined stages. Rather, it may often have been an underlying intent to impose order, system, utility, and perhaps even aesthetic appeal, on the natural and architectural landscapes, through the cumulative effect of multiple shorter-term initiatives. In this sense, "organic" may not be an entirely inappropriate description, so long as we avoid over-emphasizing geographical determinism; the need is for a balanced view, allowing for an interplay of topographical, anthropological, political, and historical factors in shaping towns individually.

Thus the absence of written evidence for strategic direction of town planning does not rule out deliberateness and forethought, even when that growth was piecemeal over time or was dictated in part by the topography of the site, as could be the case. To give one example: the initial settlement in the marshy area of Lynn relied on the creation of relatively firm areas of terrain which were a by-product from a human activity that gave no thought to facilitating habitation; while the gradual spread of the residential area westwards over the course of the Middle Ages, into spaces once occupied by river, was prompted not only by natural silting but also (and perhaps even more) by deliberate land reclamation, and building on the extended river-bank was not a matter simply of filling in available space but a intentional relocation by the merchant community to ensure direct access for their warehouses to the points where cargo ships could dock. Urban growth was to some degree an adaptation to the landscape, but it was also a re-shaping of the landscape to meet individual and community needs and ambitions – which themselves altered over time.

|

|

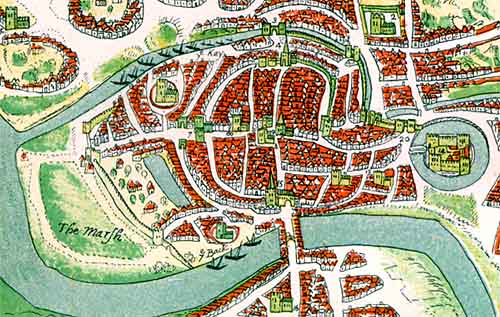

(above) Detail from William Smith's view of Bristol, 1568. Bristol was a flourishing port with a mint at the beginning of the 11th century, but its origins and measure of planning that may have gone into its layout are still uncertain. Impetus to settle there came from the protective and commercial benefits of the Rivers Avon (south) and Frome (a tributary). Early settlement lay on raised ground between these two; it was much smaller than in this depiction, a defensive bank defining its perimeter – still visible in 1568 in the almost circular course of the inner ring road – later replaced by a wall. The north-south road between bridges across the two rivers, and a cross-cutting east-west road were the original foci for habitation, their names – respectively Broad Street/High Street and Corn Street/Wine Street – indicating their importance and the commercial character of the settlement. It was the river crossing which gave Bristol its name, derived from Saxon terms meaning "place of assembly by the bridge". |

|

|

Historians have looked primarily for certain patterns in the layout of streets, property plots, and public facilities and amenities as indications of town planning. It is useful to restrict the concept of "planned town" to places where provision for settlement at a given point in time has resulted in a deliberate layout of streets and apportionment of land among multiple settlers. This can apply to the alteration or extension of an existing settlement as much as to the creation of a new one. In the latter case, where a settlement is deliberately created with some urban features, the term "planted town" has been applied; the selection of a propitious location (whether already settled or not) for a town-founding initiative is itself an indication of planning. Towns that grew "organically" are those in which deliberate decisions affecting development were made in an uncoordinated fashion over a long period of time (Norwich providing a good example). It would be dangerous, however, to think in terms of "unplanned towns", even where the street pattern has no regularity (e.g. an orthogonal grid) that is evident to perception based on modern standards. At some time in the course of urban development, consciously planned townscape components, some of them designed on principles derived as much from theology as from science, may have been introduced into more towns than is immediately apparent. Although the evidence is not always unequivocal, there are numerous cases in which town planning in England occurred on a larger scale than the gradualistic development of most settlements. This is most evident in regard to towns which were planted by some individual founder; but there are probably few, if any, towns where some measure of conscious planning did not help shape the townscape.

We should put in this category the burhs – a programme on a scale unparalleled in other European countries of that time – even though scarcity of evidence prevents us from being sure whether the importance of this programme lay in founding places that later became towns, or in giving added stimulation to market/population centres already headed in that direction. In at least some of the cases, the erection of the defensive banks of the burhs undoubtedly had some influence, if only temporarily, in defining boundaries for expansion, and in at least a few places the laying out of streets was part of the effort – indeed, historians are only gradually appreciating the number of sites evidencing planned layouts.

The king was certainly a key player in stimulating urban (or proto-urban) development, through burhs and ports and the competitive advantages (such as those already mentioned) he could give to places he favoured, including their incorporation in the organization of a national administration, which of necessity was founded upon a hierarchy of regional and local mechanisms, some based in towns. More generally, the relative peace and order that were consequent to the establishment of a national monarchy were conditions conducive to trade and urban growth. It was in the king's interest, both from a financial perspective and from that of the extension of royal authority throughout England, to develop a network of regional centres of trade and administration. Towns and kings were natural allies. Furthermore, as an absentee landlord he was less likely to act as a drag upon local initiatives. The example he set may in part have prompted his leading subjects to follow suit, and the king was supportive in assisting those subjects – lay or ecclesiastical – to develop their own market centres. The acquisition of royal licences for markets and the granting of charters of liberties, creating conditions that attracted settlers and stimulated commerce, are reflections of planning, in the sense of weighing options and making decisions.

Such decisions typically involved the surrender of some feudal control in return for new revenue sources. The combination of growth in population, agrarian productivity, and trade from the tenth century was in itself encouragement for lords, both lay and ecclesiastical, to establish markets within their estates to tap into commercial profits – which for them was the tolls and other dues from market activities – or to attract more settlers to points where trading was taking place, not least for the rents forthcoming from land and houses taken up by those settlers. This was also in fact a great age of village creation, for villages provided a more efficient way of organizing agricultural production than did scattered farms or hamlets; to some extent we should see the formation of villages and market towns as two sides of the same coin, rather than as different stages in urban evolution. Manor houses and churches (whether small parish churches or monastic foundations), were natural magnets for settlement, being sources of authority, protection and consumption. Bury St. Edmunds and St. Albans provide examples of new or revived towns with ecclesiastical patrons. Episcopal foundations were fewer than those by monasteries, the former perhaps being a facet of the inclinations or vision of individual bishops. In either case, the church was, until the thirteenth century, more active than secular lords in town foundation – not surprisingly, if we keep in mind that, as holders of great wealth and vast estates, ecclesiastical institutions were both major producers of wool and crops for export and communities of consumers with a relatively high standard of living.

The Conquest temporarily depressed the urbanizing environment as the kingdom was subjugated – Domesday Book evidences depopulation and impoverishment in a number of leading towns in association with rebellions and the subsequent imposition of castles (e.g. York, Ipswich) – and as William I imposed heavy new financial burdens on communities. But the new Norman lords, looking to England to make their fortunes, made more positive contributions to urbanization through the building of castles, cathedrals and monasteries, providing new consumer groups for existing towns or attractors for new settlers, while new settlements of French traders (and later Jews) were inserted into a few towns (e.g. Norwich).

Lynn presents an example of a multi-phase seigneurial foundation in which the episcopal lord of the manor at first converted a modest existing settlement into a town by granting market rights and building a parish church, and a half-century later a successor founded a second town alongside with its own market and port facilities. There was likely more planning of initial street layout in the latter case than in the former. It is even possible that a suburban area of settlement in the area, known as Littleport, might have been under consideration as a third market centre, although this was pre-empted by the amalgamation of the various areas into one borough. There is some indication that the foundation of Lynn may have been part of a wider programme to stimulate the development of urban centres within the bishopric. On the other hand, Lynn's example also suggests that the establishment of a market with formal commercial privileges may sometimes have been a belated recognition of trading already going on at such sites.

It was the commercial success of places such as Lynn that encouraged imitation; any investment required on the part of the founder was likely to be repaid from new sources of income (licence fees, rents, tolls, court fines etc.) generated. Where today the elite of society start up companies to build wealth, those of the Middle Ages founded communities of money-earners. The fervour for seigneurial foundation of new market centres or towns reached its peak during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries; in the same period, many existing non-urban settlements were given market rights by their lords.

In many of the planted towns, as well as some larger medieval villages, streets were laid out in patterns that appear to have consistent features from place to place, even though there may have been more than one theoretical model in circulation. New Winchelsea offers a well-documented example of a planted town with a grid-pattern plan. The English antecedents of this can be traced back to at least some of the Wessex burhs and, perhaps less certainly, to the topographical imprint left by Roman colonia. We should be careful not to read too much into identifying common patterns. A grid layout would be the natural product of a human desire for orderliness, of an intent to enable efficient intra-mural travel (including convenient connection to a central marketplace and to the defensive perimeter), and of the provision of evenly and equitably distributed building plots laid out in a manner susceptible to modular expansion; as well, it catered to an administrative mentality interested in such matters as social control and tax collection. On the other hand, orderliness and the use of measured proportion through the application of basic geometric forms were considered both an expression and a reflection of divine precepts, system, and purpose behind Creation, and we cannot ignore the influence of Christian thinking on urban design. Medieval urbanization may have been fuelled by pragmatic factors such as economic development, population growth, and defensive needs, but it is no coincidence that it was particularly vibrant as aesthetics of symmetry, harmony and decorum re-emerged in the arts, science, and philosophy during the Twelfth Century Renaissance.

|

|

The "lower town" of Carcassonne, in France, also known as the Bastide Saint-Louis, came into being after an unsuccessful siege (1240) of the fortified hilltop city resulted in the destruction of two suburban settlements between the hill and the River Aude. The displaced settlers were authorized by the king to establish a new town, independently administered, on flat ground on the far side of the Aude. Its streets were laid out on a grid pattern around a central marketplace, with two parishes – on either side of the marketplace – corresponding to the old settlements, and an entrance gateway on each side of the rectangle. This modern illustration of the planned town shows how it might have looked by the late fourteenth century, after a devastating assault by the Black Prince (1355) had necessitated extensive rebuilding in the town and strengthening of the defensive enclosure. Growing prosperity from its merchants' and weavers' involvement in the international cloth trade helped the planted lower town gradually eclipse its better defended but less well-situated parent. |

We should not place overwhelming emphasis on the grid-pattern type of town plan, for there were new towns which did not employ a grid layout. In some the layout focused on the market (such as a gathering of dwellings around the marketplace, or along the route of a highway of which a short stretch is widened to create a marketplace), or on the road linking marketplace with a seigneurial structure such as castle or abbey. In a smaller number of cases, settlement might curve around part of a castle bailey, follow the course of a winding river bank, or be confined within a peninsula. Hybrids are also identifiable. The landscape had an influence, of course; flat or sloping stretches of land, if regular, were suitable to a grid layout, while ridge-tops and rivers (whether the banks, or approaches to a river crossing) favoured linear layouts.

By the second half of the thirteenth century, the country was so saturated with markets that the heavy competition for a share in regional commerce led to the decline or failure of a number of planted towns and market centres. Some survived only as modest redistribution centres for the rural neighbourhood; a few were not able to grow further until the post-medieval period (e.g. Leeds). Nonetheless, the process of town planning and urban development continued, along much the same lines as today, most visibly through initiatives such as the building of defensive walls, the widening and/or paving of streets and market-places, and the provision of infrastructure for such things as government, commerce, and water supply, with the townsmen themselves now taking the lead.

previous |

main menu |

next |

| Created: April 5, 1999. Last update: January 5, 2019 | © Stephen Alsford, 1999-2019 |