| SOCIAL EVENTS | ||

There was not during the Middle Ages the same differentiation between sport, entertainment, and casual recreation that we make today. The term ludus might be applied indifferently to martial contests, hunting, dramatic performances, children's games, sports, adult board games, or just taking a break from the workaday life, but generally involved some kind of social gathering or interaction. All these had the character of diversion or recreation, although some also had more serious attributes in terms of, for example, skills acquisition or moral education.

On a more informal level, the medieval tavern served the same need for social gathering and recreation, and was as ubiquitous, as the modern-day British pub. Both men and women frequented taverns, although some that doubled as brothels were more male haunts. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, socio-religious gilds were providing social occasions for urban upper classes that avoided the common or dangerous aspects of tavern visits, while the crafts gilds too had social gatherings usually involving drinking. Medieval townspeople liked to make merry, and there were plenty of opportunities for it. An Italian commentator at the very end of the fifteenth century made these amusing but disparaging observations about English social habits:

"Few people keep wine in their own houses, but buy it, for the most part, at a tavern; and when they mean to drink a great deal, they go to the tavern, and this is done not only by the men, but by ladies of distinction. The deficiency of wine, however, is amply supplied by the abundance of ale and beer, to the use of which these people are become so habituated, that, at an entertainment where there is plenty of wine, they will drink them in preference to it, and in great quantities. Like discreet people, however, they do not offer them to Italians, unless they should ask for them; and they think that no greater honour can be conferred, or received, than to invite others to eat with them, or to be invited themselves; and they would sooner give five or six ducats to provide an entertainment for a person, than a groat to assist him in any distress."

[C.A. Sneyd, ed. A Relation, or Rather a True Account, of the Island of England, Camden Society, vol.37 (1847), 21-22]

Probably the closest thing to an organized sport in the Middle Ages was the tournament, which was of course for the aristocracy. But commoners also had a role to play in military operations, and so they too had recreational activities aimed at developing martial skills – notably archery and hunting. There may have been a keep-fit rationale behind some of this, and some activities appear to have been simply for the sake of exercise. At the other extreme, perhaps for reasons of increased enjoyment, activities such as archery went beyond mere practice into the realm of competition. Where there was competition there was gambling and aggression. Most outdoor sports were fundamentally races or combats, which inevitably got adrenaline flowing and excited emotions. Even indoor games often symbolised martial activities or racing; or the element of chance made them prone to cheating and to emotional upsets – dicing was one of the simplest, longest-standing, and most prevalent, particularly in taverns or gambling dens. Sports and games often come to the historian's attention because they have deteriorated into brawls or worse, giving rise to court records.

Another dimension to sporting events was that of assertion. On the individual level it might be a matter of building and maintaining a reputation – opportunities to demonstrate personal prowess and even, on occasion, take licence in challenging social superiors in a way that could not be done in other contexts. On the communal level, activities such as wrestling and hunting often involved rivalries with other communities or authorities. Hunting rights were associated with territorial jurisdiction, and were for a while sought after by urban authorities. Most recreational activities were male-oriented. However, women are occasionally found engaging in such activities, but usually of a less competitive or more solitary sort (e.g. swimming, boating, skating, gardening), or of a sedentary sort (e.g. chess). Many activities involved animals, particularly the horse which was so important to medieval society, but also wild animals or performing animals; gambling was often involved.

While some recreational activities could be healthy for medieval society, others were perceived as undesirable, and attempts were made to suppress them. Competition, and particularly gambling, too often led to criminal or antisocial acts; gangs of youths were particular sources of violence, while boardgames were targets for fraud. The king preferred his subjects to engage in activities that fostered martial abilities; so he encouraged archery (its practice being enforced beginning with the Assize of 1252, and receiving a further boost from the Hundred Years War), while prohibiting ball games. The game that by the close of the Middle Ages was beginning to be referred to as football was for most of that period considered particularly reprehensible, appearing to the authorities as little more than another expression of the mob violence that too often caused problems in towns. Yet by the fifteenth century we find the beginnings of organization in the sport, at least in London, in the form of a fraternity of football players. Mock combat with short sword and buckler, an exercise for adolescents, likewise over time degenerated into gang warfare. Yet even games such as tennis, or its racquetless counterpart handball, were the subject of bans. However, the repeated prohibitions at both national and local levels suggests that suppression was, for whatever reason, not very effective.

Games like football might take place on wasteland in or near a town, or in the streets themselves. Just as churches were foci for social gatherings, churchyards were also a place for sporting events, as they might be also for commercial transactions. However, the church authorities deplored the risks of damage this posed.

Although we often hear of recreational activities in the context of them being banned, or leading to court cases (too frequently, coroner's reports), there are other sources of information. One of the best descriptions of the spectrum of such activities available to townspeople is given by FitzStephen, whose memories of growing up in London are largely those of the more diverting side of life. He makes reference to numerous avenues for diversion:

This, we must never forget, is London, England's metropolis. But the same range of activities was available elsewhere, if on a less ambitious scale. It is evident that medieval people valued their off-work time, whether it was for casual recreation or more elaborate celebrations or competitions on the occasion of festivals. FitzStephen indicates that certain recreational activities were associated with particular days or season. Lent/Easter was particularly being a time of outdoor activity, as spring arrived; the great Carnival preceding Lent became a time for a wide range of celebrations, often to excess – Bruegel's allegorical depiction of "Carnival and Lent", although produced in 1559, compiles illustrations of many medieval recreations (while his "Children's Games" is a similar visual compendium). Such activities provided a release mechanism, while at the same time opportunities for socializing – even to the point of crossing class barriers – and in some cases rituals that helped cement or restore group solidarities.

Not mentioned by FitzStephen, largely because it was more a feature of later centuries, was the recreational element of ceremonies. Whether having a political function (e.g. swearing-in of newly-elected mayors), a social character (e.g. annual gild feasts and processions), or a ritualistic role (e.g. the Corpus Christi day procession), ceremonial occasions provided an opportunity to reinforce communal solidarity and fellowship within a celebratory context, while at the same time subtly reasserting society's hierarchical structure by distinguishing leaders from followers and associating wealth with power. Even charitable activities could disguise similar messages.

The great nobles of the kingdom travelled around their domains a good deal, accompanied by retinues. Not only because of the cost-efficiency of living off the hospitality of those under their lordship, but also because their personal presence was the most effective way of ensuring their rule was enforced, their wishes respected. Their display of power was not merely in the soldiers they brought with them, but in the magnificence – the evident visual superiority – of their parades. This was in turn aped by the ruling class of the towns, many if not most of whom aspired to rise into the ranks of gentry, and increasingly felt themselves superior, not merely economically but also socially, to other townspeople.

Townspeople did not have to wait for visits of dignitaries to engage in festivities or ceremonial. There were many festivals throughout the year that provided opportunity for conviviality or show. Some involved solemn ceremonies, others called for free-spiritedness. Christmas, Easter, Corpus Christi, May day, Midsummer, and Lammas were but a few of the times when there were communal feasting and drinking or other activities and when the streets might be decorated. Besides which the socio-religious gilds of the town each had their own special feast-days, associated with the saint to which they were dedicated.

As with sports, much medieval entertainment took place in outdoor contexts, since this permitted more communal participation. At home, those who were well-off might be able to engage minstrels or storytellers for social occasions, or amuse themselves with parlour games. But for those without parlours (the "chamber" of the medieval house) or halls, the home was mostly a place to eat and sleep, and recreation was ought out-of-doors.

In addition to communal gatherings, sports, and public ceremonies, there was a taste for music and dancing, and dramatic or comedic performances, appealing to emotions that sometimes seem less governed than those of Victorian and post-Victorian society, although perhaps the fondness for drinking was partly the cause of this.

In Anglo-Saxon England, secular music tended to be accompaniment for storytelling – whether spoken or sung – or more lighthearted tomfoolery, such as dancing or tumbling performances. The tradition of bard with harp gave way as new instruments came to the fore, and individual itinerant minstrels were joined by travelling bands. By the close of the Middle Ages, ensembles rather than solo performers were the norm.

Urban authorities themselves had occasion to hire musicians, most commonly called "waits", not just to entertain the populace or visiting dignitaries on celebratory or ceremonial occasions, but for more mundane tasks, such as noisemaking to accompany social offenders to the pillory, playing fanfares to bring audiences to order, sounding the hours during night-watch, or accompanying a contingent of the local militia to the front. At Lynn for example one of the bureaucratic officials hired from mid-fourteenth century was a bedeman, who duties included the making of public announcements, i.e. town crier; the incumbent from 1375 to 1388 was Thomas de Sutton, alias Thomas Bedeman, alias Thomas Belleman (either because of the use of a bell to attract public attention, or because he tolled the church bell to announce the death of a citizen), alias Thomas Whaite. But these various roles does not mean we should discount the entertainment element. Music was popular on most occasions, including as an accompaniment to feasting.

Dancing was also well loved, as a participative activity – perhaps nowhere more clearly expressed than in the exuberant folk dances depicted by Bruegel – or in performance. Some of those performances became increasingly dramatic at the close of the Middle Ages, as the penchant for display and disguising increased. The Dance of Death, for those able to afford professional performers, was something occasionally staged as part of pageants, to remind the audience of their mortality.

It was sometimes a thin line between a dramatic dance and a masked mime. At one end of the spectrum they were rowdy and almost anarchic – perceived as a threat to order and eventually banned. At the other end they developed into dumb pageants with ritualistic elements. A second influence on the development of medieval theatre was the celebration of divine services, which had inherently dramatic qualities and, on special occasions, came to involve the introduction of props or costumed characters from the Bible, as dramatic elements were emphasized to create an impression on the congregation.

The best-known and most urban manifestation of medieval drama was the Corpus Christi plays. They, together with other plays known to have been performed in a number of towns, are one example of the rich ceremonial life of townspeople. But ceremony with a more overt educational purpose – entertainment having a long history of being bound up with education.

The play associated with the festival of Corpus Christi was actually a cycle of performances which came to be known, in the post-medieval period, as mystery plays – not because of their content, but because the performances were organized using the craft gilds, or misteria (a term derived from the classical Latin word for "occupation" and evolving into the French métier meaning "trade" or "craft"). One or more gilds were assigned responsibility for the production and performance of one of the dramatic presentations in the cycle, with the town government overseeing and regulating the whole.

To the best of our knowledge, the Corpus Christi cycle was strictly an urban phenomenon, although by no means all towns engaged in this activity – it appears to have been only a few of the larger, more prosperous towns, particularly those in the northern half of England. Samples of the plays performed have survived for York, Chester, Wakefield, Coventry, Newcastle and Norwich, while there is evidence (or suspicion) that Beverley, Ipswich, Kendal, Leicester, Lincoln, Bristol and Worcester; Lancaster, Louth, Preston, Canterbury and London may perhaps also hosted similar performances – although at London the large number of national, civic and parochial processions, full of their own kind of drama and celebration, may have made it unnecessary to develop the play cycles found elsewhere. Plays that may or may not have a Corpus Christi association, written largely in Cornish Celtic, with the surviving copy dating from the late fourteenth century, are associated with the town of Penryn. For the gilds, production and presentation of the plays gave an opportunity for conspicuous display of socio-economic status; there is some evidence of competition between gilds to present visually impressive performances, sometimes leading to excess.

The Corpus Christi play comprised a number of individual performances, the number and subjects varying from town to town, each dramatising events or persons from the Bible, from the Fall of Lucifer to the Last Judgement. Sometimes it appears that plays were assigned to particular gilds because of a perceived association, or perhaps the gilds themselves made a choice that might serve to advertise their trades – occasionally explicit advertisements were posted, although city authorities considered this an abuse; the plasterers (who undertook construction work) might, for example, present The Creation, the shipwrights the building of Noah's Ark, the water-carriers or mariners Noah's Flood, the bakers the Last Supper, or the cooks the Harrowing of Hell. The Corpus Christi plays were not strictly speaking morality plays, although their function was partly didactic. The individual performances were often referred to a pageants, a term deriving from the crude stage (Lat. pagina meaning "plank") on which presented, usually mounted on wagons; the mobile character of the performances seems to be particular to England, whereas on the continent the locations were stationary.

Historians at one time agreed that the roots of these urban plays, which were performed in English, lay in Latin liturgical drama – particularly miracle plays – presented by the Church in the twelfth century, at religious festivals such as Easter and Christmas; they focused particularly on the life and death of Christ, although FitzStephen mentioned plays in London depicting holy miracles and the sufferings of martyrs. There was less agreement on how this evolved into the secularized form of the Corpus Christi play, and now the tendency is to emphasize a wider variety of influences on, and types of, dramatic presentation. Some point to folk-plays acted out by wandering minstrels, during seasonal revels of the common people, as a further influence, infusing burlesque or humorous elements into religious drama. The Corpus Christi play retained religious influences, such as instructional tactics derived from sermon and homily; and the Church likely encouraged and supported the presentation by laymen of drama that provided religious instruction, even in a popularized form relying on visual illustration and appealing more to the emotions than the intellect.

A major step towards the development of the Corpus Christi play had to have been the official establishment by the Pope of Corpus Christi as an important and universal festival; this happened in 1311. Since the festival took place at a time of clement weather (late May or June), it was suitable for an outdoors procession led by city and church officials in which the holy sacrament was carried through the streets to a church; the Pope authorized such a procession in 1317, and the earliest record of one in England is from the following year. Over the years this festive parade likely became more elaborate, with additional religious ornamentation introduced and in due course, it is hypothesised, static depictions of scenes from the Bible, drawn along on wagons. Brief dialogue may next have been introduced to interpret each scene; in time these pageants developed, in ways differing from town to town, into scripted plays. For the populace, the play cycle represented on the one hand a celebration of the God-directed destiny of humanity, and on the other hand a new facet of the traditional midsummer revels.

Although there is a suspect tradition that the dramatization cycle had emerged in Chester by about 1328, other evidence suggests the 1370s as a more likely period of origin. At York and Beverley, the plays were said in the 1390s to have been long-established, although this too likely does not refer back much beyond the earliest references: 1376 in York (a passing reference in a rental to a house where pageant stages were stored), and 1377 at Beverley (likewise, the context suggesting that the performances were well-established). That Corpus Christi fell in a period when daylight hours were long helped encourage the development of a cycle of performances. At York the cycle became so extensive that it seems unlikely that all pageants could have been performed on one day; by 1426, there was no time for both pageant and procession, and the latter was displaced to the following day.

The Corpus Christi play was not the only play for public entertainment and edification. The Passion play was also popular. At York, Beverley and Lincoln a play called the Pater Noster was created along similar lines to the Corpus Christi play, in terms of sections being allocated to different groups to produce. The Pater Noster, unlike the Corpus Christi play, was essentially a morality play. Morality plays appeared about the same period as gild pageants; their aim was to personify the vices and virtues. There is slight evidence for other plays – nature unknown – having been performed in York as early as the thirteenth century.

With the miracle, morality and other plays having moved out of the sphere of influence of the Church into the hands of the gilds, there was the tendency to introduce secular and even farcical elements catering to popular taste and contemporary urban perceptions of society. Interspersed with Catholic values, which mystery plays not so much taught – for instruction in these came through Church 'performances' (sermons and sacraments) – as reinforced, were sprinkled ideas that could be considered subversive. This degradation, from the perspective of the Church, led it to become increasingly critical of the plays and, after the Reformation, to succeed in repressing performances in the sixteenth century, although the legacy of the plays found its way into dramatic forms and characterizations of the Early Modern period.

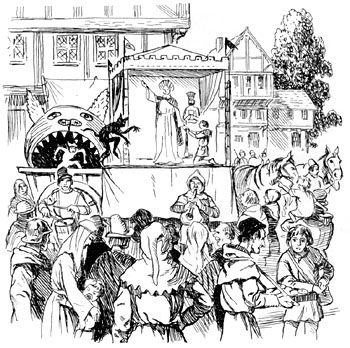

Twentieth-century depiction of performance

of a play from a pageant; the monstrous mouth

from which devils issue represented the entrance

to Hell.

CARTER, John Marshall. Medieval Games: Sports and Recreations in Feudal Society. New York: Greenwood Press, 1992.

CLARKE, Sidney W. The Miracle Play in England: An Account of the Early Religious Drama. New York: Haskell House, 1964.

COULSON-GRIGSBY, Carolyn. "Medieval Drama: Myths of Evolution,

Pageant Wagons, and (lack of) Entertainment Value." On-line

Reference Book for Medieval Studies, n.d.

http://www.the-orb.net/non_spec/missteps/ch5.html

CRAIG, Hardin. English Religious Drama of the Middle Ages. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1955.

CUMMINGS, Lucienne, ed. "Early Drama and Ritual Performance". Part

of Virtual Norfolk: Norfolk History Online.

http://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20050606184058/http://virtualnorfolk.uea.ac.uk/drama/index.html

DAVIES, R.T., ed. The Corpus Christi Play of the English Middle Ages. London: Faber and Faber, 1972.

HENRICKS, Thomas S. Disputed Pleasures: Sport and Society in Pre-Industrial England. New York: Greenwood Press, 1991.

JERZ, Dennis. G. The York Corpus Christi Play

http://jerz.setonhill.edu/resources/PSim/intro.htm

MCLEAN, Teresa. The English at Play in the Middle Ages. Windsor Forest: Kensal Press, 1983.

NELSON, Alan H. The Medieval English Stage: Corpus Christi Pageants and Plays. Chicago: University Press, 1974.

REEVES, Compton. Pleasures and Pastimes in Medieval England. Oxford: University Press, 1998.

SMITH, Lucy Toulmin. York Plays: The Plays Performed by the Crafts or Mysteries of York on the Day of Corpus Christi. New York: Russell and Russell, 1963. (originally published 1885)

WARD, A.W. and WALLER, A.R., eds. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature, volume 5: The Drama to 1642. Cambridge: University Press, 1907-21. (published online by Bartleby.com, 2000)

WILLIAMS, Arnold. The Drama of Medieval England. Michigan: State University Press, 1961.

(N.B. there is no shortage of works on medieval English drama. Nelson's study is particularly recommended for being organized as a survey of urban settings.)

|

|

main menu |

|

|

||