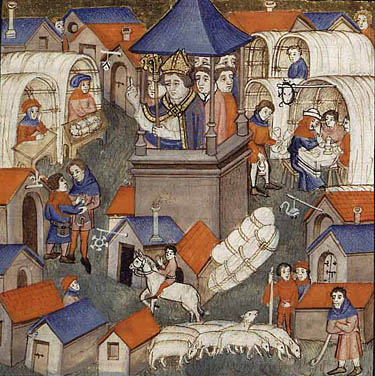

The annual opening ceremony of the foire du Lendit, a Parisian fair

held in June, involved the Bishop of Paris giving his blessing from a specially built structure.

The fair attracted mainly merchants from numerous cloth-making towns in northern France, but

was also known as a livestock fair. All the buildings depicted here, in

a fourteenth century French manuscript, the Pontifical de Sens, were erected for

the fair.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des Manuscrits

Part of the Medieval Fayre held annually at Colchester,

in parkland north of the castle, near the bank of the River Colne.

Photo © S. Alsford

Several fairs were held at Colchester in the Middle Ages. The oldest belonged to the abbey of St. John, one being a four-day fair in June held on the green outside the abbey; it was granted to the abbey at its foundation and confirmed by Henry I in 1104. The second was a May fair licensed by the king in 1157, to be held on wasteland southwest of the castle; the latter fair is not evidenced at any later date and may have been discontinued. If so, perhaps it was because the June fair was itself a sore point between the burgesses and the abbot. For one thing, the burgesses complained that the fair caused them a loss of revenue that was contributory to payment of the borough fee farm, and successfully sued the abbot for an annual payment in compensation. For another, they resented the abbot's judicial jurisdiction associated with the fair. In 1272 the bad blood erupted at the fair into a violent clash between townsmen and tenants of the abbey.

The hospital of St. Mary Magdalene was granted a fair in 1189, held on an adjacent green; although not a major event, with a duration not exceeding the festival of the patron saint, it was in 1318 able to draw traders from Suffolk, Norfolk, and London.

The borough itself did not receive a fair licence from the king until 1318/19 – an eight-day event in October (including Sunday) – although it may perhaps have been mounting an unauthorized one, just within the southern town wall, for some years previously [Janet Cooper and C.R. Elrington eds. The Borough of Colchester, Victoria County History of Essex, vol.9 (1994), p.272]. In the sixteenth century it was taking place along the High Street, with stalls grouped according to type of wares, manufactured by various kinds of cloth-makers, leather-workers, metal-workers, basket-makers, and other artisans, in addition to sellers of fish and dairy products.

In conjunction with the re-enactment (2013), in Crysler Park,

Ontario, of a battle from the War of 1812, a "merchantsí row" was created to reflect

a tent camp of sutlers (mobile provisioners of armies). The similarity to

the Colchester Fayre is evident and participants were much the same kind of traders

in modern reproductions of historical commodities.

Photo © S. Alsford

Fairs were rather like markets writ large. They attracted a larger clientele of buyers and sellers, drawn from further afield; local and regional merchants would rub shoulders with foreign counterparts and with purchasers from royal and aristocratic households and from monasteries. Rather than just goods grown or manufactured locally and regionally, they brought together goods from across the country and from abroad, in particular luxury goods.

Better-quality cloths were certainly the key commodity – principally of English and Flemish towns, yet also to a lesser extent of producers in France and Italy – but furs and hides, wine, spices, dyestuffs, horses suitable for nobility, hunting birds, were also well in evidence, as was the mainstay of English commerce, wool, and (to a degree) imported building materials and hardware. Such goods were present in greater quantities than they would normally be in markets, and were traded in bulk. Where a region had some specialized industry, products of that industry might also be shown at closer (if minor) fairs in an effort to reach a wider consumer market. What you would not find much, if any, of at the major fairs was foodstuffs such as fruit, vegetables, dairy products, bread, which did not travel long distances well – this did not preclude it being of some interest to regional buyers; the notable exceptions to this being wine, because of its relatively high value, and fish preserved by salting or smoking.

At modern re-enactments of fairs, a few of the stalls seem to capture some of the flavour of what might have been displayed for sale at medieval occurrences. At the very least these modern events, serving recreational priorities more than economic imperatives, attract traders (specializing in reproductions of medieval items) from far afield, just as medieval fairs did.

Cloth merchant's booth, Colchester Medieval Fayre.

Photo © S. Alsford

|

|

Photos © S. Alsford

Furs and hides (tanned or untanned, more transportable than livestock) were materials

that could be bought at fairs by merchants to sell elsewhere to artisans who would convert

them into clothing and other commodities. As these booths at the Tewkesbury and Colchester

fairs show, such raw materials are still in demand by artisans who create costumes for

medieval re-enactors.

Photos © S. Alsford

Fairs provided an opportunity for the products of specialized regional industries

to be marketed to a wide-ranging audience, perhaps more to stimulate demand than

to sell large quantities.

Photos © S. Alsford