Part of the terrace of Abbey Row cottages, Tewkesbury;

the abbey's exceptionally large Norman bell-tower rises at rear.

Photo © S. Alsford

Tewkesbury abbey, founded by the town's seigneurial lord and erected during the opening decades of the twelfth century, to supersede an earlier Anglo-Saxon monastery, dominated the borough economy and owned many of the properties in the town. This was the case with the row of terraced cottages built either progressively or perhaps in two phases of development, but all under one roof, between the late fifteenth to early sixteenth centuries along part of the main street running through Tewkesbury, at the abbey end of town. Now known as Abbey Row Cottages, encompassing nos. 34 to 50 Church Street, the terrace comprised some two dozen single-bay houses (until some were demolished), each just under twelve feet wide. Although the name Abbey Row is a modern designation, at Chester the well-known Rows are a name whose medieval use was always to designate groupings of shops; the earliest references to such rows relates to shops in the commercial centre of the city. The term 'row' was also applied in many places to streets, lanes, or stretches of marketplace characterized by the clustering of some particular trade.

The row of cottages at Tewkesbury probably represents a financial investment by the abbey to generate new income from rents. It is believed the houses were let to merchants or artisans and that the front rooms facing the street served as shops; this was evidently part of the design plan, with a view to ensuring tenants remained able to pay their rents. It reflects a wider trend to build shops into the ground-floor of residences. Although it is not common to find such a string of shops incorporated into a building design, this was no innovation, for the famous Norman House in Lincoln, a stone complex probably built by a member of the local Jewish community, included a row of four ground-floor shops with no access to the rest of the building. The row of shops of the Abbey Road cottages represents what might be considered, by only a small stretch of the imagination, a medieval precursor to the modern strip mall; certainly this was an initiative that was repeated numerous times in twentieth century England to create groupings of shops, with living quarters above, in urban neighbourhoods both in and outside of city centres.

(above) This section of the Abbey Row cottages has

at centre the unit restored as a medieval merchant's house, with shop window shutters

closed.

Photo © S. Alsford

One of the cottages now houses the Moore Countryside Museum, while another cottage nearby has been restored to show what it may originally have looked like as the residence/shop of a late medieval merchant. On its front one of the main differences between the latter and the other cottages in the row are that the upper storey windows are covered with a less rigid and non-transparent material; although when built they were equipped with wooden shutters that slid open laterally along grooves. The most noticeable difference, however, is the wide, street-level shop window restored to the cottage. This would have been closed up with wooden shutters overnight, but during the day the shutters would be taken off to allow customers to look into the shop and converse with the shopkeeper. Alternatively, the shutters, supported by one or more posts or trestles, may have been tilted to a horizontal position to create, immediately outside the window, a counter for displaying shop wares; in the case of some of the houses, notches in building-frame timbers on either side of the window opening could have held poles that helped support such counters.

The jettied upper storey of the row would have offered some protection for the counter and customers, as well as the wall of the lower storey, from rain and perhaps from chamber-pot urine emptied from upper floor windows into the street. The doorway on the left side of each shop has a moulded ogee-shaped head common in late medieval English architecture and typical of the Abbey Row cottages. The lower lateral beam of the house's timber frame serves as doorstep and offered some protection from the flooding to which Tewkesbury, situated in a flood-plain, was vulnerable.

Diagonal view of the shop window (shutters removed) of the

restored merchant's house; the front door of the building is just beyond the window,

and the interor entrance to the shop, off the access corridor, is visible through

the window.

Photos © S. Alsford

The front door opened onto a corridor which ran past the shop, but gave immediate access, from the side, to the shop; it also gave access further in to the living quarters, and at the far end to the service rooms and garden. The hall lay behind the shop; part of the hall was open through the upper storey to create a void for smoke from the hearth to drift upwards rather than disperse into living areas. Behind the hall were the service rooms (kitchen and buttery). A steep, almost ladder-like, staircase on one side of the hall led to the upper storey where were two bedrooms: one above the hall and shop, the other above the service rooms. A latrine would likely have been located in the garden at rear of the house.

The shop would have been sparsely furnished, probably with: a table where theshopkeeper, if an artisan, might work during the day, or otherwise organize his money, positioned by the window during opening hours; and shelves, a cupboard, or a chest for storing some of the shop goods out of easy reach of pests. A lean-to at the back of the house, perhaps an after-thought by planners or added by early tenants, offered a more private alternative as artisanal workshop (if it was undesirable for customers to see wares prior to them being in a finished state).

composite © S. Alsford

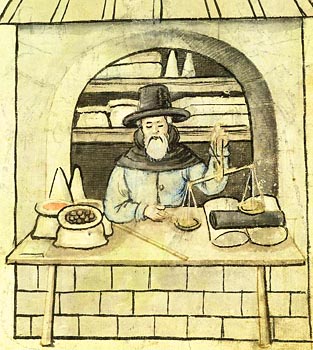

(above) Superimposing the shop front over the depiction of

a draper's shop from the Tacuinum Sanitatis gives a rough sense of how the shop

may have appeared to a passer-by ca.1500.

(below) Something similar is seen in the portrait of Nuremberg merchant George Weinbrenner

(d.1533), shown behind the counter of his shop (note the external supports for the counter)

weighing some substance he is spooning onto his scales. On the counter are several bags

(of spices?), sugar-loaves, small bolts of cloth, and a measuring stick. Shelving

at rear contains more cloth and cones of sugar.

From the Hausbuch der Mendelschen Zwölfbrüderstiftung

The building of terraced housing (multiple, uniform residences within an elongated unit of a single architectural composition) of which Abbey Row is an example, was, because of the need to accommodate growing urban populations, a late medieval trend which became progressively stronger in the post-medieval centuries . Such terraces were often built along land on the fringes of church precincts, facing lanes of secondary importance, or in outskirt areas less desired by the more prosperous businessmen who preferred to live near the marketplace. They required an investor with some capital, another factor favouring the Church's involvement. Few medieval instances have survived, in part because easy targets for redevelopment, yet also because simply not as common as they would become in later times.

Indeed, they were not common enough to require the formulation of a concept such as 'terraced housing'. They might instead be referred to sometimes as 'rows' – the oldest known terrace to survive in England being Lady Row in York, although we may remember that at Great Yarmouth a shortage of terra firma resulted in intensive construction of housing along a series of very narrow lanes known as rows, running in parallel off a couple of main through routes. Or sometimes as 'renters' –; for those who built them were looking to create a steady revenue stream in rents from tenants tending to be, in the Middle Ages just as much as in the twentieth century, less affluent, if not marginalized, inhabitants, such as journeymen or unmarried women (although the poorer ones would have lived in lodgings). The Abbey Row cottages, which were relatively close to the town centre and provided with hearths, must have been intended for a slightly better clientele of artisans or small-scale traders at an early stage of their careers.

Such houses might seem somewhat cramped by modern standards, but were adequate as a first home of a small family with little furniture. The terraced house of my own childhood was only a few feet wider than those of Abbey Row, and little different in its one-up one-down floor-plan, with a front room, living room behind, steep central staircase leading to the two upper floor bedrooms, and projecting from the rear a kitchen with third (smaller) bedroom above. In the case of some, though not all, medieval terraces, the front room was a shop or workshop. Terraces similar to that of Abbey Row, combining shop and residence, are known, also from the latter half of the fifteenth century, from Canterbury and Coventry [see Anthony Quiney, Town Houses of Medieval Britain, Yale University Press, 2003, 263-65].

This row of shops in Lavenham, although a modern insertion in fifteenth or sixteenth century

buildings (renovated in the 1980s but retaining much of the original street frontage),

suggests what the Abbey Row cottages would look like if still fronted by shops today.

It has been given the name Merchants Row.

Photo © S. Alsford

Early settlement at Lavenham was probably around St. Peter and St. Paul's church and along the street leading from it (now Church Street); this subsequently spread further up that route as it became the High Street, after the manorial lord, the Earl of Oxford, received a royal licence (1257) for a market and a three-day fair at Whitsun, changed to Michaelmas in 1290. This may have encouraged some members of the farming community to pursue as an alternate or supplementary source of income cloth-making, an industry whose fullers and dyers were assisted by the presence of tributaries of the River Brett (one running along what came to be called Water Street).

By the early fourteenth century the cloth industry there was becoming organized and profitable, despite the fact of having to rely on wool from other parts of England (local wool being of inferior quality). The industry so took root there that by 1524 Lavenham was ranked as the fourteenth wealthiest town in England, although about to experience a rapid decline, as it was outcompeted by cloth-making centres elsewhere. This prosperity attracted new settlers, necessitated the expansion of the street system into what had formerly been agricultural lands, and resulted not only in the rebuilding of the church on a lavish scale but in the construction, between about 1460 and 1530, of most of the timber-framed buildings that still stand in Lavenham – thanks to economic decline having resulted in little later redevelopment – and several shopfronts are still well-evidenced, as later owners of the houses could not afford to remodel.

(above) In this late fifteenth century house on Lady Street,

Lavenham, the ground floor incorporates what was originally a shop-front with three

openings and awning. It probably represents a merchant's shop, lacking an

exterior counter associated with the windows, which were instead to give light for

customers to view stock inside the shop. The doorway is also original.

(below)Facing Lavenham's marketplace is the impressive Guildhall of Corpus Christi,

with an older shop window (at left) still visible.

Photos © S. Alsford

No.26 Market Place is one of a pair of Lavenham buildings adjacent and attached to the guildhall custom-built 1530 as the new home for a socio-religious gild founded before 1477 by wool and cloth merchants of the prospering town. These structures, which occupy one entire (and slightly curving) side of the marketplace, give a good sense of a late medieval streetscape of timber-framed buildings, the timbers left unpainted to turn a natural grey. In the photo above, the building shown at left, now used as a tea-room, had prior to 1530 been owned by a wealthy mercer and was a residence incorporating a shop, whose front has been preserved. This combined shop/house is similar in its basics, though not so much in its layout and size, to the Tewkesbury cottages. Two closely adjacent arched windows provided for customers a view of goods displayed inside the shop; they was equipped with upper and lower shutters (today nineteenth-century replacements for what were probably similar originals), the lower doubling as a counter outside the window and the upper as an awning over the counter. Of the two doors to the right of the shop window, the nearer and narrower was the entrance to the shop, taking up as little space as possible in order to maximize the display potential of the window, and to reduce the number of people who could pass through at once, tus giving more security. The wider doorway was the entrance into the residential section and gave onto a passage leading to a door at the back of the house. The cross-passage also had doorways into the shop and another room at its rear, perhaps a storeroom. The residential quarters included a hall facing the marketplace, two rear service rooms accessed from the hall, and upstairs chambers reached via a narrow staircase. Unlike the Tewkesbury shop/house combo, that at Lavenham, occupied by a wealthier tenant, was furnished with a chimney stack.

A late fifteenth-century house originally from the Sussex borough

of Horsham, with ground floor shop-front; preserved at (and partially reconstructed)

by the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum.

Photo © S. Alsford

Horsham is heard of in a charter of 947, but was not mentioned in Domesday; it remained a market town (with markets twice weekly) until modern times. The house shown above was situated in a street whose earliest known designation was as Butchers Row, located in the middle of a large marketplace and representing the encroachment of permanent structures, incorporating shops, where stalls had once been. This house has two shops, side-by-side, each with doorway and display window; the right-hand shop has access to the upper storeys and was probably operated by the householder, while the other (slightly larger) would have been rented out. Each shop has at its rear a small hall with smoke void and the house timbers show evidence of the regular use of fires there, perhaps for cooking meat or pies, for example.

(above) A similar style of shop front is seen in

Augustine Steward House, facing Tombland in Norwich. Here

Steward was born (1491) though

not raised, the son and apprentice of a mercer; he took up occupancy at some point

after his father's death (1504), probably undertook some rebuilding after fire gutted

the neighbourhood in 1507, and began to acquire other properties in the wasted

neighbourhood. Family quarters were in the upper storeys, a shop on the ground floor,

and a stone undercroft provided storage for trade goods.

Photos © S. Alsford

(below) The House That Moved in Exeter obtained its name in 1961

when, to protect it from demolition, it was moved from its street-corner emplacement

(which explains the showy timber-framing on two sides) to a new location. It was

a merchant's house of ca.1500 with one main room on each of the three floors: on

the ground floor a shop, with kitchen at rear, on the first floor the hall, and

on the second floor a bedroom and storeroom.

While late Medieval shops share with modern ones a preoccupation with maximizing display windows, this may not have always been the case earlier. The Assize of Measures (1196/97), which prescribed standards for the size and quality of cloths, also prohibited clothiers from installing covers over their shop-fronts, reducing the light in the shops, presumably so that brightly-dyed cloths did not suffer from light damage and/or imperfections in the textiles were less perceptible to customers.