In the fourteenth century Norwich, whose defensive walls enclosed an area larger than intra-mural London, had fifty to sixty churches, but six times as many taverns. Its great marketplace had at least one tavern at, or near, each corner – in some cases two – and one in the interior, near a corner of St. Peter Mancroft churchyard. Marketplaces, and shopping streets running off them, were natural places to establish taverns and inns because they were the principal attraction of a town for both locals and visitors building up a thirst or tiring themselves out. The comparison between churches and taverns is hardly fair, since churches could accommodate larger groups than most taverns, and we may assume that urban churches attracted weekly as many users as taverns, if not more; but it is indicative of the fact that taverns had become as characteristic of medieval English towns as the pub was in the twentieth century. Both churches and taverns met real social needs.

However, medieval churches were, and modern pubs are, quite a bit more conspicuous than medieval taverns, many of which looked little different from private houses, while some were hidden below street level; most any residence was amenable to conversion into a tavern for some part of its lifetime, and custom-designed establishments may mainly have been built for wealthy proprietors who planned to combine consumption with brewing and/or to provide not only a 'public bar' but private booths, as well perhaps as some guest accommodations. Large commercial inns required more planning, often incorporating a street-accessible courtyard lined with rooms of different sizes for drinking and dining in public or private; such places anticipated servicing various clienteles, from casual drinkers to overnight guests, travelling merchants to pilgrims.

From a copy of the Tacuinum Sanitatis in the

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des Manuscrits

(above) The sign of the bell hanging above the doorway suggests

that this establishment may be an inn rather than a tavern. Certainly the customers

being offered a welcoming drink by the proprietor are travellers – one riding

a finely caparisoned horse, the other a pedlar with a pack of trade goods on his back.

The inn may look small, but the artist had no need to show much of it to convey

the character of the place.

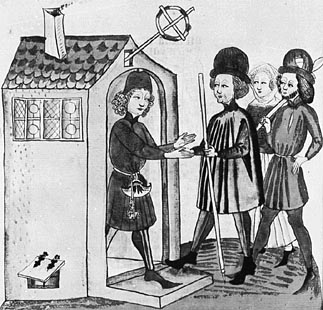

(below) The proprietor stands on the threshold of his establishment

to welcome a pair of travellers, whom his wife, at rear, has perhaps flagged down on

the road. The saltire (a diagonal cross) over his doorway is one traditionally designating

inns, which were often located near crossroads. The proprietor has keys and a purse

attached to to the belt at his waist. This illustration accompanies a

cautionary tale about a deceitful

Toulouse hosteler. The smoking chimney suggests comfort inside for guests, while

the window allowing light into a cellar suggests that part of the building to be

the tavern element.

From the Schachzabelbuch, a German translation (1337), of

Cessole's

De Ludo Scachorum

Medieval depictions of taverns and inns – it being hard to tell, in some instances, which type of establishment is being portrayed, and indeed the dividing line was a little fuzzy – generally show rather modest-looking structures and denote their role by incorporating standard iconographic features, such as an ale-stake or other business sign, and a proprietor (sometimes male, sometimes female) welcoming clients and often proffering food or drink.

(above) In this marginal illustration from a fourteenth century

Flemish copy of the The Romance of Alexander an innkeeper tries to attract

a client with the offer of a drink.

(below) Here, on the other hand it is the alewife who entices a customer with

a flagon of ale, which display of the broom from the alehouse announces to be freshly

brewed; in the moral tale this illustrates, the customer (a hermit, unused to drink)

gets drunk, rapes a miller's wife, then assaults the miller when he tries to

intervene.

An illustration added in England ca.1340 to an older French manuscript

known as the Smithfield Decretals; British Library

This reconstruction (in the Canadian Museum of Civilization)

of the public part of an inn from late seventeenth century Louisbourg shows it

a simple building barely deserving the name of inn, more akin to medieval taverns

than modern pubs. Its provision of beer, hot food, and a mattress on the floor, all

in a single room, would have served visitors to the French colony who could not

afford better.

Photo © S. Alsford

The Red Lion Hotel, facing onto Colchester's High Street.

Note the wagon-way entrance.

Photo © S. Alsford

The Red Lion site incorporates cellars dating to ca.1400 and the earliest above-ground part of the building to ca.1470, but this was modified and expanded in 1481-82 when the Duke of Norfolk had a town-house constructed for his use, rising to three storeys, with a wagon-way in the centre, communicating between the street and a courtyard at rear; brick piers and arches were inserted in the cellar to support the cartway. The building was richly decorated with carvings, including (in the spandrels over the archway into the wagon-way) St. George confronting the dragon. It was converted to an inn ca.1500, and by 1515 the town's fish market was taking place in front of the inn. The middle storey jettied out further than is apparent from the photograph, as it was in modern times underbuilt with shop fronts.

The rear and wagon-way side of the well-known Mermaid Inn, Rye.

Photo © S. Alsford

The Mermaid Inn proudly proclaims on a sign on its front that it was last rebuilt in 1420, which is a reasonable approximation. It is thought to have been built ca.1200, and the vaulted cellars, cut into rock, survive from that build. Conceivably it began life as a cellar-based tavern with house above, or as a vintner's house whose storage cellar made it a good location for a later tenant to turn into an inn. Situated on what was then known as Middle Street, Rye's main street, leading from its busy Strand quayside (the town being one of the Cinque Ports) to the commercial centre of town, it was in a good location for a tavern. It brewed its own ale and offered lodgings for a penny a night. It was destroyed in the French raid of 1377 but rebuilt on a larger scale and became the town's leading inn, used by the borough authorities (at least by the sixteenth century) for official feasts. Much of the present timber-framed structure, with jettied upper storey, dates from the fifteenth century rebuild, although with some modifications in the Tudor period. A partially covered wagon-way connects the street with the rear courtyard.