Gilt silverware (drinking vessels, sauce-dishes, and other tableware) part of the

Norwich City Regalia and Civic Plate Collections (England's largest public collection

of secular plate), now displayed in Norwich Castle museum, though some is still used

at ceremonial occasions; some of the civic plate dates back to the Tudor period.

Photo © S. Alsford

Gold, silver, and precious stones have been highly valued as long as there has been written history, and the Middle Ages was no different. These materials were in scarce supply in England. Very little new gold was produced by mining or panning in medieval western Europe, and most was obtained by melting down older products, particularly gold coins from the East, for re-purposing; yet some of this existing stock was siphoned off by Byzantium via a trade imbalance. Silver was relatively more plentiful, being mined in a number of European countries, including England, where obtained as a by-product of lead mining. Consequently the precious metal content of medieval European currencies was primarily silver.

The more capable of the craftsmen, known as goldsmiths, who applied to such materials a range of technical skills, requiring scientific knowledge, patient and precise work, and aesthetic taste, to fashion functional, decorative, and ornamental goods tended to be esteemed and well rewarded; they often rose into the ranks of the socio-economic elite of the towns where they were based. This does not mean that the occupation was a guaranteed path to fame and fortune, but that it offered these artisans greater opportunity than most for bringing them to the attention of the high-and-mighty. For goldsmiths were needed and patronized by the most important and powerful members of society: kings, nobles, and high-ranking churchmen, since the display of gold, gilded, and silver objects – whether on one's person or in one's everyday surroundings – and the gifting of such objects to others were considered a show of high status, wealth, and power, while their accumulation and use by churches was viewed as a way of praising God. From a more pragmatic perspective, such objects were also a means of investing and storing wealth.

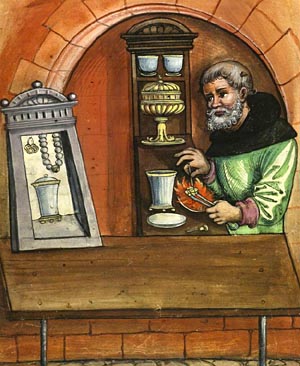

From the Hausbuch der Mendelschen Zwölfbrüderstiftung

Posthumous portrait of Nuremberg goldsmith Pakraz Storchel

(1465-1530) shows him in his shop, working at a table behind his window-counter.

With a pair of tongs he holds a piece of gold over a fire and uses a jeweller's tool

to shape it. Other of his products are seen: on the table a gold-rimmed silver cup,

with lid nearby; on display furniture at rear more functional silver cups and a large

gold standing cup; on the shop counter a metal display case with another gold-rimmed

lidded cup and some jewellery. His products, his clothing, and the location of his shop

on a paved street all suggest his business had at one time enjoyed success. Yet later

it had declined to the point where, at age 56, he had to accept charity in the form

of a place in a retirement home for needy artisans, and just a little under nine years

later he went out to a meadow and hung himself. He was not the only goldsmith to have

to seek refuge in the home; for instance, a few years earlier passed away another inmate

who had once been a goldsmith, though forced to earn a living as a watchman in his

later years.

Goldsmiths became most in evidence, as towns and trade grew together, in the larger cities, where nobles and gentry did their shopping and often had their own houses, and where there were cathedrals and/or monasteries in need of impressive furnishings and ceremonial objects – wealthier monasteries might employ their own goldsmith. But even small towns might have a goldsmith among their residents, for their work was not so often on the large items of plate, standing cups, caskets, chalices, reliquaries, candlesticks, croziers and crowns, or the like, whose relatively few survivors, escaping later re-purposing (mostly preserved after finding their way into Church treasuries or, to lesser extent, the collections of urban corporations), so awe the modern viewer. Rather, goldsmiths' bread-and-butter was rings, brooches, belt and knife decorations, and other small items of jewellery or personal ornamentation, and perhaps also small cups, dishes and spoons. For its heraldic arms, London's Goldsmiths' Company chose as icons of its craft a standing cup and a brooch.

(above) Gold ring that once belonged to merchant John Sumpter,

who was elected bailiff of Colchester in 1422 and 1424. The central, revolving section

has four sides, each with a different decoration – one a dolphin, the others

saints – which would have made it a relatively expensive item for a burgess

to own and confirms Sumpter's prominence in Colchester society.

Colchester Castle Museum.

(below) Jewellery from the Fishpool hoard, buried in

Nottinghamshire in 1464, probably by a wealthy merchant or noble who feared losing

his valuables to mishap during the Wars of the Roses. Here we see a heart-shaped brooch,

locket (set with a sapphire), cross (with a ruby and four amethysts), chain, rings

(one set with a turquoise), and a miniature enamelled padlock with inscription suggesting

it a love-gift.

British Museum.

Photos © S. Alsford

London goldsmiths represented the peak of the profession in England, being motivated to excel by their access to a key clientele: a large number of religious houses and churches, the nobility present at court and, of course, the king himself. A few of the latter's commissions to them have been mentioned elsewhere. Virtually nothing survives of these products for the monarchy, but we have detailed images of some as part of two portraits of Richard II in coronation robes, including crown and bejewelled collar; one portrait was contemporary and possibly by Gilbert Prince, the other a sixteenth century painting based on the earlier one. We may wonder whether the collar depicted in the original portrait might be one of the pair Richard had commissioned for his personal use from London goldsmiths Drew Barantyn and Hans Doubler, for the sum, or down-payment, of £66 13s.4d. in 1393 (the year before the probable date of the portrait), to be made of gold and ornamented with pearls and precious stones; in 1408 Barantyn would make such a collar for Henry IV for at substantially larger cost. Much of Henry's jewellery was produced by breaking up and melting down Richard II's golden treasures, with the gems therein put to new uses.

Detail from the sixteenth century portrait of Richard II

(which shows the jewellery to better effect), by an unknown artist.

National Portrait Gallery

Richard loved finery that showed off his royalty. He amassed a substantial treasure – inherited from his forebears, commissioned by himself or his queens, and seized from political enemies he executed or exiled, of which an inventory (ca.1398) survives [published in Jenny Stratford, Richard II and the English Royal Treasure, Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2012]; one of the pieces of jewellery described therein resembles the famous Dunstable Swan. His Lancastrian successors combined similar display jewellery with politics, by commissioning collars and badges that incorporated, or were even formed from, symbols or the letter S to signify affiliation of their adherents, and other aristocratic houses followed suit, using their own symbols or letters; those collars given to men below knightly rank were silver, those to knights were gilded, while base metals were used for collars given to servants. Bury St. Edmunds merchant John Baret mentions two such Lancastrian livery collars among the items bequeathed in his will, and a small carved figure of him on his tomb shows him wearing one of the collars.

The Dunstable Swan Jewel (named after the location where

unearthed by archaeologists) was made ca.1400 from gold then mostly covered

with white enamel worked to represent feathers, with traces of black enamel

still remaining on the legs and eyes and pink on the beak; around its neck is

a gold crown to which the chain is attached. Swans were an emblem of several

leading noble families, notably the Bohuns, and the jewel may have been worn

as a livery badge for a supporter of the House of Lancaster (Henry Bolingbroke

having married into the Bohun family and adopted the emblem). Like gilding,

enamelling was a specialty of goldsmiths; London goldsmiths certainly produced

enamelled work and some were capable of the special technique required for

this piece of jewellery. British Museum.

Photo © S. Alsford

Arguably the best artist's depiction to have survived from medieval Europe of a goldsmith at work is that by the Flemish painter Petrus Christus in 1449. It was later assigned the title St. Eligius in His Workshop on the assumption that, following tradition, it portrayed the patron saint of goldsmiths (though in England St. Dunstan had that role), and a halo was even added to the painting in the nineteenth century. However, it is now thought to portray some prominent goldsmith operating in Bruges in the time of the artist, and may conceivably have been commissioned for display in the goldsmiths' gildhall in Bruges. The painting gives us a good look at the interior of a goldsmith's shop/workshop, where a young betrothed couple, whose dress indicates them to come from a wealthy background, is buying a wedding ring, which the goldsmith holds with his right hand, apparently preparing to weigh it on the auncel held in his left, to determine its value; it has been speculated that the young woman might be his daughter, though the figures may simply represent generalized customers.

Petrus Christus's portrait of the goldsmith.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

A wide range of products is seen in the shop, along with tools of the trade. On the shelf at rear and above the goldsmith are silver-gilt vessels, the two with handles intended to function as flagons, while the third (at left) is a standing cup intended for display. Hanging from the shelf are rosaries and a silver-gilt belt buckle which would have been fitted to the kind of belt seen on the left side of the counter. Hung on the wall below the shelf are items of jewellery, and a pair of shark's teeth worn as a charm against poison. On the lower shelf are (left to right) another standing cup, two touchstones (used to test the purity of gold), a piece of coral (for goldsmiths dealt in various sorts of rare or exotic materials, some considered talismans, which further enhanced the goldsmith's reputation), an assortment of unmounted pearls and gems, a cylindrical reliquary, and a box containing a number of finger rings. On the counter in front of the goldsmith are some of his weights, the open-lidded box they were taken from, and gold coins of different countries (either payment for goods sold, or raw material for melting down).

The merchandize shown in Petrus Christus' painting is perhaps intended only to be a representative sample. A London Letter-Book recorded in 1398 an inventory of the commercial stock of Walter Pynchon, a Cornhill resident, taken following his murder in Winchester, his goods being appraised by goldsmiths Drew Barantyn and Hans Doubler at just over £600. The two most valuable items were a royal chaplet and a royal nouche (an ornamental piece of jewellery, probably an elaborate brooch, perhaps in an animal shape, decorated with gems) at £100 apiece. Also of high value were 11 unmounted rubies, and he had too 27 diamonds, 2 sapphires, 30 pearls, and a small box of crystals, all of lesser value. The stock of gold objects further included a collar with a falcon as its centrepiece, 65 rings, 15 nouches, a couple of pieces (perhaps pendants) in the shape of harts, an episcopal ring and mitre, and a chaplet decorated with pearls. In silverware, the stock comprised a ewer, two flagons, two candlesticks, three gilt beakers, a salt-cellar, a paxbred (tablet inscribed with a holy image, used during communon), and twenty-four spoons.

Walter Pynchon does not loom large in city records nor is there any reason to think he was one of the leading goldsmiths or jewellers of the city; rather, he seems to have come into that occupation in a roundabout way. A goldsmith named John Pynchon had been alderman of Cornhill ward 1389-92. A few weeks after his death in September 1392, John's infant son Thomas, through the agency of unidentified 'friends', perhaps associated with his step-mother, borought a suit in the mayor's court to require John's executors – who included his brother Walter, a mercer – to hand over the one-third share of his goods and debts due him according to city custom. The executors argued that the custom was not applicable in this case, and the court was uncertain. Based on the terms of John's will which they produced in court, the executors offered Thomas £600; this, they claimed, was one-third of the residue of the deceased's estate after other legacies had been paid, excluding certain debts owed John by unnamed magnates that were considered uncollectable. At the court's advice, Thomas accepted this settlement. However, it would be years before he saw his inheritance, for in August 1393 Walter, having a couple of months earlier paid off, in money and jewels, the step-mother with her widow's portion, obtained custody of young Thomas and his inheritance, probably in the form of stock from John's business; whether he held the stock in safekeeping on Thomas' behalf or attempted to trade with it, converting his own business into that of a jeweller, is unclear, though the latter seems more likely for medieval merchants were not wont to let wealth sit around stagnating. It was after Walter's death that the men who had stood surety for his custodianship requested the seizure of his stock (hence the inventory) for the benefit of the young ward, who would take possession of the value thereof upon coming of age in 1406; that the valuation of the stock amounted to pretty well what Thomas was due may indicate it does not represent the total of Walter's stock, only enough to satisfy the obligation to Thomas.

A thirteenth-century treatise on letter-writing [parts of which are transcribed and translated by Martha Carlin, "Shops and Shopping in the Early Thirteenth Century: Three Texts," in Money, Markets and Trade in Late Medieval Europe, ed. L. Armstrong et al., Leiden: Brill, 2007, pp.517-30 ], anonymous but known only in copies of English manuscripts, in its effort to expand readers' vocabulary gives a description of a goldsmith's operations, stock and equipment, somewhat idealized but likely based on the author's knowledge of actual shops. The author begins by noting that goldsmiths worked, through casting or beating, with metals (mainly gold and silver, but also some baser metals), which were used to create forms that might be solid or hollowed, polished smooth or embossed, as well as with gemstones, which they shaped or engraved; he would also work with wooden items, such as by plating them with gold or silver leaf, or adding metal feet and rims to mazers. Their stock should, the author goes on, comprise chalices, cups (with and without lids), flagons, pots, platters, dishes, saucers, salt-cellars, basins, cruets, spoons, crucifixes, reliquaries, candelabra, crowns, rings, brooches, chains for necklaces or pendants, and studs for decorating girdles. In terms of equipment, he should have a small bellows, tongs, hammers, anvil, a grindstone, a hare's foot (for polishing gold and silver, and for sweeping up fragments of metal), a leather apron (for collecting the fragments, not to be lost), smelting supplies, strips of gold for orphrey work, silver wire (likewise for decoration), and a painted tray on which he could display to customers samples of his best work.

A silver spoon of late fifteenth or early sixteenth

century.Museum of London.

Photo © S. Alsford

Norwich's goldsmiths were organized in a gild by mid-thirteenth century. They lived mainly in parishes bordering the marketplace, and in the market their shops were grouped along the north-eastern edge. At London the goldsmiths congregated along Cheapside, the main shopping street, at the centre of which was constructed in 1491 Goldsmiths' Row to house fourteen of their shops. By the close of the Middle Ages their shops were so numerous that they were the aspect of the city that particularly impressed a Venetian visitor.

In 1179/80 the goldsmiths had been one of nineteen London groups fined for forming gilds without paying (as the weavers and bakers were doing) a licence fee to the king, who was nervous about such associations anyway; that the goldsmiths incurred by far the largest fine – although it is not clear these fines were ever paid – is an early indication of their relative wealth among the London crafts. For it seems probable that many, if not most, of those groups comprised, predominantly or entirely, men of particular trades, even though only the goldsmiths, pepperers, butchers, and clothworkers were explicitly identified. The others were identified by the individual who was then alderman of the gild and several with Bridge, which might refer to the ward (where fishmongers, woolmongers, and vintners, for example, were plentiful) or to the recent project of rebuilding London Bridge. These groups may have taken the form of socio-religious gilds, some of which had as one of their purposes raising funds towards the costs of the bridge project; which does not preclude them having a close association with some occupational group – indeed it was the tradesmen of London who had most to profit from a new bridge.

When next (1272) the goldsmiths are evidenced as an organized group, it is as a socio-religious gild dedicated to St. Dunstan; in 1327 this gild obtained a royal charter authorizing its existence. Twelve years later the gild purchased a merchant's residence, just north of Cheapside, to become the first hall known of any London gild. How many of the late medieval goldsmiths of London were themselves craftsmen, and how many were essentiallyshopkeepers employing technicians such as jewellers, refiners, or goldbeaters is difficult to say.

Mercantile occupational groups are absent from, or unidentifiable in, the list of 1180, so we cannot say that the goldsmiths were at the apex of London society. Analysis of the city aldermen in the first half of the thirteenth century [Gwyn Williams, Medieval London: from Commune to Capital, rev. ed., London: Athlone Press, 1970, 319] shows that drapers, mercers, and vintners outnumbered goldsmiths in aldermannic ranks, with the pepperers almost as numerous as goldsmiths – although these monolithic trade designations disguise the range of goods in which most leading merchants dealt. But we can say in general terms that the goldsmiths were one of those groups trading in luxury goods that were influential in civic government and, collectively, substituted in certain regards for the merchant gild not found in London.

The importance of the goldsmiths stemmed not only from the precious goods in which they dealt and the high-ranking customers they supplied, but with their close connection with the minting of royal coinage and maintenance of its quality; they were perhaps not coiners in the sense of the men who stamped out coins, but rather engravers of coin dies and assayers of the precious metals cointent of coins. Gregory de Rokesle for instance was one of the London goldsmiths and civic leaders whom the king put in charge of minting; to combat growing problems, such as clipping, which had caused the value of English coins to deteriorate, Rokesle oversaw a recall and recoinage project to restore the integrity of the coinage, as well as the transfer of the royal mint to the more secure location of the Tower. Edmund Shaa, just four years after completing his apprenticeship to a London goldsmith, was (1462) appointed engraver to the royal mints, holding that post for twenty years, during which time he also held the top executive positions in the Goldsmiths' Company and the city's administration; his nephew John Shaa succeeded him as engraver and was later made joint master of the Mint and elected mayor of the city.

London's goldsmiths were prominent not only because of their number, wealth, and international reputation, but also because they had a role in supervising goldsmithing across the country. A statute of 1300 (chapter 20) makes the first reference we have to standards applied to the craft, including the assaying of gold and silver products by gild wardens and the stamping of those found acceptable (if large enough) with a sign in the form of a leopard's head. It also prohibited the setting of fake gems into jewellery. The statute applied not only to London, but to goldsmiths in any other English towns, who were required to adopt the same mark for their work and to arrange for a representative to go to London to familiarize himself with the procedure.

The charter granted the goldsmiths in 1327 reiterated the responsibility of the wardens to police the manufacture and ensure gold goods were not exported; to facilitate this supervision, goldsmiths' shops were not to open outside the Cheapside neighbourhood where they had long been focused. Soon after, we find the London company appointing goldsmiths in Oxford (their gild first mentioned 1348) and York to ensure the royal regulations were followed. In 1363 it was required that individual maker's marks also be applied to products, although it is not clear that this was widely practiced for some time. In 1370 the Goldsmiths' Company instituted marking of goldsmiths' weights, which had been standardized ten years earlier. Then in 1478 the post of assayer was created, operating out of the Goldsmiths' Hall; all London goldsmiths were required to bring their products to be checked and receive 'hallmarks', with a continental system of marking adopted to identify place and year of manufacture. Those of other towns continued to be subject to supervision by the London wardens, or their appointees.

The long row of goldsmiths' shops stretching across

the Ponte Vecchio in Florence (only a few of which are seen here) gives a slight taste

of what an English aurifabria might have looked a little like. However,

the Ponte Vecchio jewellers were in fact introduced during the seventeenth century,

to replace unwanted butchers who had monopolized the shops on the bridge

since the mid-fifteenth century.

Photo © S. Alsford

The distribution of mints around the country would have helped foster provincial goldsmiths. A family of which was associated with the mint at York, as well as with civic administration, in the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries; the city's register of freemen suggests that York continued to have a relatively high number of goldsmiths throughout the Middle Ages, though we are still talking about a small number – a house once owned by one, William Snawsell, who was also city mayor (1467), has been restored to a medieval state as Barley Hall. The old capital of Winchester had a stretch of the High Street named for the goldsmiths and other shops were in the initial part of a nearby turning off the High Street; in a survey of 1148 they were among the craftsmen most frequently identified as property-owners, and they remained among the wealthier citizens, though their numbers seem to have declined over the course of the Later Middle Ages, as Winchester increasingly lost its old importance.

But less is known about the organization of goldsmiths outside of London, and in most towns they are unlikely to have been numerous enough to warrant forming gilds. Coventry, for example, supported only a small handful at any given time and we hear of no gild associated with them before 1523, when even then they could only form one in conjunction with other metalworkers. At Salisbury although we hear of goldsmiths in a list of trade gilds drawn up in 1440, they had to be grouped with other metalworkers for the administrative purpose for which the list was made; yet in 1423 Salisbury had been one of seven towns, other than London, which parliament allowed to have a distinctive mark to apply to goldsmiths' products. The other towns were York, Newcastle upon Tyne, Lincoln, Norwich, Bristol, and Coventry.