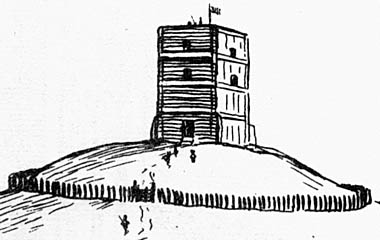

The earliest Norman fortifications, many of them erected in towns, were quickly built and comprised wooden towers, set on mounds built up from earth excavated from an encircling ditch. In the centuries immediately before and after the Conquest, urban defences are similarly believed to have been largely earthworks and palisades. Naturally, no such palisades have not survived to the present day, although the reconstructed Norman castle and village at Stansted Mountfitchet gives a rough idea of such fortifications.

A small stretch of the embankment and palisade

at Mountfichet Castle, with watch-tower and gateway, as well as

embedded stakes to hinder attackers.

Photo © S. Alsford

Only once the Norman hold on England was more secure was there leisure to upgrade these defences, building more strongly in stone. Such intrusions within urban landscapes were alien to the English, who were used to perimeter defences, and were likely resented. They continued to be thorns in the side of the community, for Urban castle precincts remained "liberties" outside the jurisdiction of city authorities for some time, and came to serve primarily as administrative (rather than military) bases, and as such were sometimes competitive with borough administration.

As a northern rebellion in 1068 showed, York was a key urban centre that the Normans had to control firmly. As soon as it surrendered, William I had a keep built and garrisoned; after a second rebellion the following year, in which the tower was damaged, he had a second keep put up, on the opposite side of the River Ouse; this unusual step of introducing two military bases in one town showed his determination to subdue the citizenry. An incursion by the Danes later the same year saw the castles captured, but William once more hurried north and reasserted his authority. We are not sure which of the pair was the first built, but the more strategically located one, probably the original, was later (1245-65) rebuilt in stone and expanded into a larger complex with a bailey that included barrack hall, stables, storehouses and workshops, chapel, kitchen, and prison.

This model of York castle, displayed in Clifford's Tower,

shows (in top right-hand corner)

the keep (referred

to during the Middle Ages as "the great tower") atop its motte,

with the bailey to its left and the whole protected by water

defences: two rivers and ditches flooded by damming one of

the rivers. The mound on which the original wooden keep

was built is entirely artificial, made in layers: at bottom a

layer of clay; atop it soil mixed with clay and stones, then a

layer of rammed earth (again mixed with clay and stones);

more layers of earth at the top, and finally a wooden

platform set atop tree trunk piles reinforced with stones.

Photo © S. Alsford

Another of the locations William the Conqueror chose for a Norman castle was an Iron Age hill-fort in Wiltshire that was on its way to becoming the original Salisbury. The Romans had established a small town next to it and, after their departure, it continued to serve as a refuge for residents of farmstead settlements clustered in the vicinity. The hill-fort's defensive bank and ditch were kept in repair, perhaps even strengthened, during the period when the Wessex monarchy was establishing burhs; one of the names applied to the site was Searoburh. Its settlers were joined by other refugees from nearby Wilton (one of Alfred's burhs), after it was attacked by Danish raiders in 1003.

A castle there – comprising a keep, atop a ditch-surrounded motte, and a hall to accommodate the king – had been begun by 1070, when William, having subdued all England, felt secure enough to pay off his troops at the site. The Saxon settlement there may have had urban characteristics. The presence of a castle stimulated its economy and its growth, as did the transfer of the diocesan centre there (1075) and construction of a small cathedral. This was the essence of the town subsequently known as Old Sarum.

Around 1100 the timber tower was superseded by a stone keep, and in the 1130s the bishop, having been given control of the castle, replaced the wooden hall with a large stone palace and built a gatehouse at the entrance of the inner bailey, which was later given a perimeter wall. He also began a curtain wall to surround the entire settlement atop the prehistoric fort (although it was never completed). By this time the town was not restricted to land bordering the inner bailey, but had expanded into a sizeable suburb, outside the east gate entrance to the earthwork. There is some evidence of planned development of this area in the twelfth century and the focus of the town seems to have gravitated there.

However, for a number of reasons, including jurisdictional conflict between the garrison and the cathedral clergy, the lack of space to expand the cathedral, and inadequate water supplies for the local population, the bishop relocated the cathedral to a site beside the river Avon, where another town grew up and prospered, as the present-day Salisbury; the old cathedral was abandoned and, although the castle remained in use as sheriff's residence and gaol, the town of Old Sarum became impoverished and depopulated, eclipsed by its new neighbour, whose markets were more competitive.

(above), Seen from some distance, part of the

the prehistoric outer earthworks of Old Sarum; on the left side

of the section shown can just be made out the secondary mound created

to support and helf defend the inner bailey of the medieval castle.

(below, top) The mound of the inner bailey is seen beyond ruins of

castle buildings in the outer bailey; only the flint core remains

of the ruinous castle, the outer stone facing (which would have

given a smoother and whiter appearance to the buidings) having been

long since scavenged for other uses. (below, bottom) The sloping base

of the keep was designed to make it more difficult for besiegers

to undermine the tower.

Photos © S. Alsford

The remains of the Norman keep at Canterbury give a better sense of mass than those at Old Sarum, but nonetheless ruinous. It had been preceded, at a different location (in an angle of the city's decaying Roman walls) by one of the earlier wooden towers erected by the Conqueror, in the months following his victory at Hastings, built atop a Roman burial mound heightened by earth excavated from a large ditch dug around it.

In the 1080s a stronger castle was begun nearby, just inside the Roman south gate, and again incorporating part of the Roman wall. Twenty-five residents' houses had to be pulled down to make room for the new castle and its ditch. its massive three-storey stone keep was built in the early twelfth century. After its military value had declined, the castle continued in use as the county gaol.

When dressed in Caen stone, the keep of

Canterbury castle might have resembled an undecorated version of

the Norwich keep (see below).

Photo © S. Alsford

As the leading town in East Anglia, Norwich was another natural choice for a Norman stronghold. Its initial castle was in place by 1075, when it underwent a siege, and rebuilding in stone was underway about two or three decades later.

Recent excavation of part of the bailey has confirmed Domesday evidence that the creation of the castle required clearing the site of numerous Late Saxon houses and at least two churches, as well as covering over two cemeteries (over 150 burials), one probably related to a third church. Its mound was enlarged to support the stone replacement, and a bridge was later built between the motte and bailey, along with a gatehouse. As with the other cases mentioned above, it was used primarily as a prison from the late thirteenth century, after its use as a fortification had declined, and the city had protected itself with its own walls.

The Norwich keep gives us our closest

impression of how an urban castle may have looked in the thirteenth

century. although the blank arcading decoration makes it atypically

ornate. It was built of Caen stone around a flint core, with its lower

part faced by flint, a plentiful local building material that characterizes

many of the city's surviving old buildings. The flint facing was replaced,

and the other part of the facade restored, in the nineteenth century

using Bath stone.

Photo © S. Alsford