Compared to some of the walled towns of continental Europe, the urban defences of English towns are rather less striking, visually, At most places they have not fared well through the post-medieval centuries, for at few places were defences needed after the conclusion of the civil War of the seventeenth century. Much of their fabric has been torn down in the course of urban exansion and redevelopment (notably provision for better traffic circulation), and only growing concern for heritage preservation in the nineteenth century and growing desire to exploit the tourism potential of historic structures in the twentieth has assured the survival of at least parts of a number of urban defensive circuits.

Extract from a sixteenth century Flemish

illustration in a manuscript of John Lydgate's Siege of Thebes

(inspired by, and to an extent a mid-fifteenth century continuation of,

Chaucer's Canterbury Tales). The illustration shows a group of mounted

pilgrims with, in the background. a city that is evidently Canterbury. The rendering

of Canterbury is sufficiently accurate in its broad strokes, that it was likely

based on an eye-witness description.

Canterbury was encircled by a wall about one and a half miles in circumference. The Lydgate llustration shows an extensive stretch of the walls, including 8 round towers and one gateway. Braun and Hogenberg's birds-eye view of Canterbury (ca.1580) shows the entire circuit, in lesser detail, incorporating just over 30 towers. However, it is now believed there were 24 interval towers, a few square, most round (or, technically, horseshoe-shaped, since they were open-backed). There were six gates providing access through the walls during the Middle Ages.

Canterbury had been walled by the Romans in the late third century. Those defences were still sufficient to hold off, in 1010, a besieging Danish force for twenty days, but were eventually overcome. The surviving medieval stretches are essentially repaired and re-heightened Roman works. We know that repair work was being carried out around 1166, and archaeological evidence suggests some rebuilding in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Notwithstanding such efforts, a royal commission of enquiry found, in 1363, that the walls were in bad disrepair; in places the Roman walls had been reduced to little more than half their original height. Although the city bailiffs subsequently took action to remove encroachments on the wall and ditches, repairs to the walls may not have been underway much before 1378, when the bailiffs were authorized to engage masons from the county, and the king permitted the collection of murage for five years.

A series of further murage grants covered the rest of the century. A survey conducted in 1402 showed that most of the circuit had been rebuilt. A further grant in that year may have been intended to finance work on one short stretch of wall still needing attention. The last murage grant expired in 1408, and in the following year the city authorities were licenced to acquire properties to generate income to offset costs of maintenance of the defences. The same late fourteenth century building programme also saw new towers added to supplement the handful of Roman towers, and renewal of the Westgate, although other gates had to wait until the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century before they were rebuilt.

A stretch of wall on the south-east side of

Canterbury, part of the late fourteenth century rebuilding effort.

Its crenellations are now missing. Note the keyhole gunports in the tower.

Holes near the top of this and other towers were for supports for a

wooden platform used by defenders. There is no indication (.e.g from

Lydgate's illustration) that such beams were extended out to allow

erection of the hoardings known from some continental town defences.

Photo © S. Alsford

Five of the city gates, along with almost half of the walls, were demolished during the nineteenth century, under pressures of street widening and other urban redevelopment. Once more stone from the walls (and from the castle) was carried off for use in public works. Parts of the wall and towers are now incorporated into or obscured by later buildings. Short stretches were reconstructed in the twentieth century.

As in the case of Canterbury, it was the threat posed by the Hundred Years War, together with the insistence of the king, that spurred on the citizens of Southampton to serious effort on their defences, although Southampton had had no Roman defences to use as a foundation. Initiatives prior to the fourteenth century had been either half-hearted or inadequately financed, and only parts of the town were protected by earthen ramparts and/or stone wall when the town suffered a damaging raid by the French in 1338. Much of the town walls were built in the decades that followed.

An arcaded stretch of town wall facing

medieval Southampton's west quay, where the River Test ran into

the sea. There are in fact two

layers of wall here: the outer layer

being the arcades built to strengthen the inner layer which

comprises the stone fronts of merchants' houses/warehouses, whose

windows and doorways can still be identified in the rear layer.

The arcade layer supported a walkway protected by battlements.

This external arcading is the only known example in England, being

a response to a particular and apparently atypical challenge.

Photo © S. Alsford

The completed defensive enclosure was roughly rectangular, over a mile in length, and incorporated 29 towers and 7 gates. About half of the walls, towers, and gates still stand, some of them well preserved, some fragmentary. Some features are the only examples to survive in England.

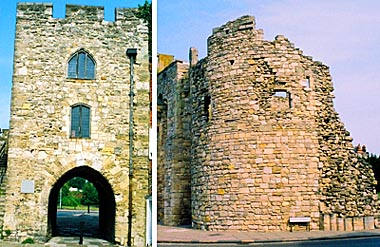

Two of the gateways through Southampton's walls.

(left) The West Gate, a comparatively simple tower built in the 1380s,

stands just south of the arcaded wall (see above), whose walkway runs

into its centre storey. It gave access onto the west quay and

was fitted out with a double portcullis. Through this gate must

have passed the armies of Edward III (1346) and Henry V (1415) as

they embarked on ships bound for successful campaigns in France.

Gunports built into the gateway were later converted to windows.

(right)The Watergate was built in the early fourteenth century on

the south side of the town. Mercantile cargoes were unloaded on

the shore there, before the town quay was built in 1411. The gate

was a customs collection point, staffed by the Water Bailiff.

The gateway proper, along with adjacent walls, was demolished in

the nineteenth century, but part of the drum tower on its western

side, seen here (with remains of merchants' houses to the rear),

has survived.

Photos © S. Alsford

God's House gate and tower stand at the

southeast corner of Southampton's defensive circuit. Named after

a nearby hospital, which owned a small quay just outside the gate,

it started life as a simple gatehouse (at left), built in the late

thirteenth century and furnished with a portcullis. Following the raid

of 1338, it was extended to add the section to the left of the archway

and a guardhouse above the gateway. Ca. 1417, the three-storey tower and

adjacent two-storey gallery were built. This was part of a wider effort

to modernize the defences, and the tower's role was to provide a fort in

the event of an attack from the sea. The tower. projecting out from the

angle of the walls, was designed to serve as a platform for artillery and

an armoury (ground floor), and it provided living quarters for the town gunner.

It was restored, from a ruinous state, in the twentieth century.

Photo © S. Alsford

The city walls at York are some two-and-a-half miles in length, but do not comprise a complete circuit, for the citizens relied partly on the obstacles of the Rivers Ouse and Foss – the latter bursting its banks (as a result of diversion of water into the castle moat) to form a shallow lake on the eastern side of the city, known as the King's Fishpool. One consequence was the need to protect the city at either end where it was intersected by the Ouse; this was done by stringing chains between pair of towers on opposite banks. For most of their length the walls stand atop an earlier defence, in the form of an earthen rampart; this placement made it unnecessary to build the fourteenth-century walls as high as they would otherwise have needed to be. All that would have been necessary was to remove the wooden palisade and to prepare a firm foundation for the stones.

This photo of the exterior face of part of

an eastern stretch of York's wall, with one of the interval towers,

shows how the relatively low wall obtained height by being placed

atop the earthen rampart that pre-existed it. The rampart sloped down

to a water-filled ditch. Although long since filled in, the ditch

is remembered along part of its stretch by the name of the raod that

covers it: Moatside Court.

Photo © S. Alsford

The greater part of York's walls still stand, together with 34 of the 39 interval towers and all four of its main gates. Despite periodic proposals to demolish the walls, the preservationist lobby prevailed, and only four postern gates and the barbicans of three of the main gates met that fate in the post-medieval centuries. The remaining barbican is the only English urban example still standing.

York's Walmgate Bar, fronted by its barbican.

The gateway's inner arch dates from the twelfth century, and the first

documentary eference to the gate is mid-century; but most of the gateway

(rising two storeys above the arch) and barbican were built in

the fourteenth. On the left side of the photo can be seen the wall

leading to the Red Tower.

(See another view)

Photo © S. Alsford

York's walls were built mainly from a Yorkshire limestone probably brought in by river, although some of its stones appear to have been cannibalized from Roman structures.

(above) Lendal Tower, on the north bank of the Ouse, was one of

a pair of towers supporting a chain across the river. Each tower

was staffed by a "custodian of the chain", responsible for raising,

lowering, and maintenance. The structure is first heard of in 1315,

when a simple circular tower, but was much altered in later centuries,

particularly as adapted to non-military purposes.

(below)The Red Tower is the terminus of a stretch of wall (part of

which is seen here, rebuilt 1502) that led towards Walmgate Bar. It

stood on the southern edge of the King's Fishpool. An addition to

the main defences, it was built in 1490, using brick, which was cheaper

than stone. The resentful city masons, thus put out of work in favour

of the tilers (bricklayers) were suspects when a tiler was murdered

and the tools of others were broken or stolen. The Red Tower may

be another instance of a fort built for artillery; certainly it

was equipped with guns in 1511. It originally had a flat roof and

was surrounded by a deep ditch.

Photos © S. Alsford