| |

OUTSIDE THE WALLS

|

| 1 |

Crouched Friars

They established a friary here before 1272, perhaps taking over

an earlier wayside hospital, to which function it had returned by the

end of the Middle Ages (as well as serving as the meeting place for the

Gild of Holy Cross).

|

|

2 |

St. John's Abbey

Founded 1095/96, to the south of the southern suburb of the town,

the

Benedictine abbey replaced a small pre-Conquest church. The original abbey

was destroyed by fire (1133) and gradually rebuilt then expanded.

After the Dissolution, the abbey came into the hands of the Lucas family

(gentry). It, along with the rest of the Lucas property, was largely destroyed

during the siege of Colchester in 1648, except for the 15th century gatehouse.

|

|

3 |

St. Giles

Probably built in the first half of the 12th century for the use of

tenants and servants of the abbey, given its location within the abbey

precinct and the fact that the boundaries of the parish lay largely

within the abbey demesne. Possibly it succeeded an Anglo-Saxon wooden

church, dedicated to St. John, that was on the northern part of the

abbey site, just prior to the abbey's foundation. St. Giles was badly

damaged during the siege of 1648.

|

|

4 |

St. Botolph's

The earliest ecclesiastical building on the site may perhaps have been a minster

church dedicated to this saint, a 7th-century East Anglian abbot (after whom the

coastal port of Boston was named); this strongly suggests an Anglo-Saxon origin

for the structure. Churches with such dedications are not uncommonly found near

the entrances to settlements, for the saint was a patron of travellers. The presence

of a Roman cemetery around the site has even caused speculation that a church might

have stood there in much earlier times. The first St. Botolph's probably

functioned as the parish church of the

southern suburb; it was then

served by a small college of priests. In the last decade of the 11th

century it became the

Priory

of St. Julian and St. Botolph, the first

Augustinian

priory established in England, and as such granted authority over all

subsequent Augustinian foundations in England. Reverting to the role of

parish church after the Dissolution (if indeed part of it had not continued

in that role throughout the Middle Ages), when its conventual buildings

were pulled down, the church itself was badly damaged during the siege

of 1648.

|

|

5 |

St. Mary Magdalen

Founded as a hospital by Eudo the Steward,

to support four leprous residents, its chapel became a parish church and (unlike the hospital

per se) was able to survive the Dissolution. However, the

medieval church was replaced by a Victorian building in the

mid-19th century.

|

|

6 |

Magdalen Street

The road leading down to the port has been considerably foreshortened

by the map-maker.

|

|

7 |

The Hythe

Perhaps the port for the Roman city; in the late Middle Ages it was

referred to as New Hythe,

a different haven (Old Hythe) having been used in the Saxon period.

Building of a footbridge there was licensed in 1407, on condition it not block

the passage of ships.

|

|

8 |

St. Leonard's

A good-sized church here served the parish around the port during the

12th century, but surviving fabric is no earlier than late medieval.

|

|

9 |

East Street

The road pasing through the East Gate, down to the East Bridge, led to

routes into Suffolk (e.g. to Ipswich and Harwich).

|

|

10 |

North Bridge

There was a bridge here from Roman times. In the Middle Ages there

was a suburb on the far side of the bridge. The bridge marked the

boundary of the borough jurisdiction over the Colne fishery.

|

|

11 |

(site of) North Mill

A grain mill until the Black Death; in the second half of that century

it was converted to fulling.

|

|

12 |

Middle Mill

A grain mill until the Black Death, after which it was converted to

fulling, but rebuilt to handle grain at the beginning of the 15th

century.

|

|

13 |

East Mill

|

|

14 |

Hythe Mill

There was a fulling mill somewhere near the Hythe in the late 14th century;

a grain mill had been built before 1428 by the bailiffs and community.

Both were derelict by the end of the Middle Ages.

|

|

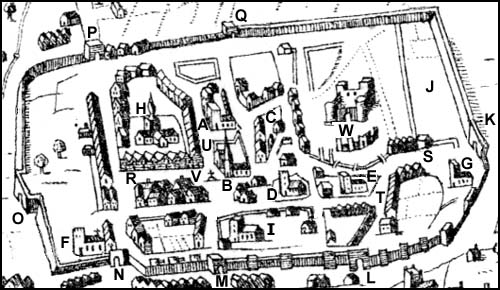

| |

WITHIN THE WALLS

|

This is a clickable imagemap. |

|

A |

St. Martin's

The tower and some minor elements date from the 12th century, while

much of the rest of the fabric is late medieval. There are some

reasons to think there may have been a church on the site in late

Anglo-Saxon times, perhaps even as far back as the end of the Roman

occupation.

|

|

B |

St. Runwald's

Likely of late Saxon origin, judging from the dedication. Before it lay the main

market of the borough, and the medieval shambles were adjacent. Its central

placement within the High Street, without any surrounding churchyard, suggests

it could have been an intrusion into an already built-up area, possibly built

as a chapel serving the marketplace and only later acquiring parochial status

and a detached cemetery. However, an alternative hypothesis is that the original

street passed south of it but widening of the street to serve as a marketplace

involved demolition of buildings adjacent to the church, leaving it isolated

within an open area. It was itself demolished in 1878.

|

|

C |

St. Helen's chapel

Local legend – perhaps

inspired by the impressive Roman walls – had Helen

as a daughter of the mythical King Coel, ruler of Colchester, and

as the mother of the Emperor Constantine. Neither has historical

foundation; but more significantly St. Helen became viewed as patron

saint of the town – her image was featured on the community seal.

The same medieval tradition had the chapel being restored in 1076 by Eudo

the Steward; if true, this might suggest an Anglo-Saxon origin, and there

is some indication the chapel was built atop the remains of a Roman

structure. Eudo gave it to the Abbey as part of his foundation

endowment and Henry II's grant of a fair and a fair site beside the

chapel was probably to fund a chantry in the chapel. But in 1290 the Abbot

was convicted of neglecting to provide a chaplain to celebrate in the chapel

during part of each week. Perhaps in part because of the resulting

impoverishment and decay of the chapel, ca. 1320 John de Colcestre, the rector

of Tendring (apparently a member of a prominent

burgess family), endowed a chantry there with numerous rents and land

to support a chaplain, and made the bailiffs and community the effective

patrons; they subsequently placed the chantry under the administration of

the Gild of St. Helen's (a fraternity of which many leading townsmen, as

well as some county dignitaries, were members) although retaining control

over presentments. It is possible this history reflects two chapels

of the same dedication: the earlier somewhere neighbouring the castle,

the later (possibly originally envisaged as a hospital) just west of it

on a site in Maidenburgh Street owned by St. Botolph's priory; yet it may be

that the abbey, having lost interest in a chapel perhaps originally created

to serve the castle but with inadequate or unrealizable financial endowment

for an expanded function, simply conveyed it to the priory, opening the way

for a refoundation.

|

|

D |

St. Nicholas

In existence at least by the 12th century, but rebuilt in the 14th, and

again in the 1870s, finally to be demolished in 1955. Parts of the

church had Roman walls for their foundation, although the Roman structure

was probably secular, not ecclesiastical. The position of the church,

close to the centre of the walled borough and at one end of the

High Street marketplace (the dedication being to a patron saint of

traders) could suggest an early origin, perhaps around the tenth or

eleventh century when the High Street seems to have re-emerged as

the socio-economic focus of the town.

|

|

E |

All Saints

There remains minor evidence of Norman work in the church, although it is

not impossible that there was an even earlier church, given the location

and the incorporation of brickwork from an even earlier Roman structure

(this part of town being the forum/basilica). It was expanded in the

14th and 15th century, with a tower and other additions.

|

|

F |

St. Mary's-at-the-Wall

Built on the site of a Roman house, with the original church perhaps of

Saxon date (judging from burials in the vicinity), it may have been

created as, or come to be, the private church of an estate of the Bishop

of London (a soke outside the jurisdiction of borough authorities).

Joseph Elianore obtained royal

licence in 1338 to found a chantry there which during the 1340s he endowed

with numerous lands and rents. The earliest known school in Colchester was

located here in the 15th century. The church's proximity to the wall made

it a defensive position, and target for the besiegers, in 1648. It was

ruinous when rebuilt in the next century, to be demolished (except for

its tower) in 1872.

|

|

G |

St. James

A church stood here from at least the 12th century (although that may

have been a rebuilding of an earlier structure). There was further and

substantial rebuilding in the 15th century.

|

|

H |

St. Peter's

The only Colchester church mentioned by name in Domesday, when evidently

already well-endowed with lands. Its key position near the junction

of two major streets also indicates its importance in the town. The

surviving medieval fabric is, however, 15th century. The depiction in

1648 still reflects the medieval cruciform plan of the church, with

a prominent tower (replaced in the 18th century) at the centre.

|

|

I |

Holy Trinity

It still has its Saxon tower, dating to ca.1000, constructed in part from

brick and tile from Roman structures; there is evidence that part of the

church dates even earlier. Parts were rebuilt in 14th and 15th

centuries.

|

|

J |

Grey Friars

This Franciscan priory, whose grounds occupied the north-east corner of

the land within the walls, was founded before 1279, and possibly

by 1237. Little has been found by way of remains.

|

|

K |

East Gate

Badly damaged during the siege of 1648, the remains were torn down a

few decades later.

|

|

L |

Botolph's Gate

Destroyed in 1823.

|

|

M |

Schere Gate

A postern.

|

|

N |

Head Gate

Removed 1756.

|

|

O |

Balkerne Gate

The western entrance to the walled city during Roman times (remains of

the Roman gateway still stand), it fell out of use towards the end of

the Roman period and was subsequently blocked; the road leading there

from East Gate was thereafter stopped at North Hill, with traffic being

diverted to the Head Gate as an exit to roads leading westwards and to

London. The Balkerne gate was in later times thought to have been a

fort. It was once thought that a postern gate existed further south

in the western stretch of wall near St. Mary's, and may have been used

as entrance/exit during medieval times; but this was subsequently

discovered to have been only an opening for a drain to pass through

the wall. We can therefore conclude that the map's creator is

depicting the Balkerne.

|

|

P |

North Gate

|

|

Q |

North Schere Gate

|

|

R |

High Street

This east-west route was the main one through the town; it ran along

the crest of a ridge and follows quite closely one of the streets of

the Roman fort/colonia, except that the east end was diverted slightly

when the Norman castle was built. As the centre of the town, it was

the location of various markets specializing in particular goods. The

point marked by the "R" was the site of the medieval corn market.

|

|

S |

East Street

|

|

T |

Botolph Street

Site of the fair held at the opening of oyster season.

|

|

U |

St. Martin's Lane

The Jewish quarter was primarily focused here, nearby market and

castle.

|

|

V |

Moothall

It is curious that this is not identified on Speed's map. Though our earliest

mention of it is in 1277, it had been built probably as early as the

mid-twelfth century, as a two-storey stone building facing onto

the High Street marketplace, with a hall placed above an undercroft that

was partially above-ground. The hall must have served as the court-house.

Alterations in 1373, which included converting the undercroft into a wool market,

extended the front (southern face) of the building into the marketplace, with the

addition of steps up to the entrance, a roofed porch, and shops on either side of

the porch. The building extended northwards with a rear yard where market stalls

could be put up, as well as housing for council-chamber, bureaucratic offices,

and gaol – though whether these were original features or later additions

is unclear. The moothall was demolished in 1843, borough administration

having long outgrown the building's facilities. At that time a Norman doorway and

flanking windows, elaborately decorated, were discovered therein (sketched before being

pulled down). The architectural and decorative styles reflect a French influence

evidenced elsewhere in England by ca. 1160; one of the carved figures might just

possibly have represented King Solomon, whose reputation as a wise judge would have

been an appropriate reminder to officials presiding over the borough court.

After the moothall's demolition, a new town hall was built on the site.

|

|

W |

Castle

Medieval tradition held that the castle

had been built atop the foundations of King Coel's castle. It has been

suggested that this might reflect the former occupation on

part of the site by the residence of an ealdorman or even an East Essex

king.

|

|

History of

medieval Colchester

History of

medieval Colchester History of

medieval Colchester

History of

medieval Colchester