unprocessed wool

Photo © S. Alsford

Even though reclamation of waterlogged or forested lands for agricultural use, alongside improvements in land management and agricultural techniques and technologies, resulted in production of greater surpluses of grain that could be funnelled into commerce, in terms of the export trade (which brought silver into England to support coinage), it was wool that was England's real wealth, the most important raw resource within its economy. From the Anglo-Saxon period on, wool and other rural resources helped feed and clothe growing urban populations, enabling them to concentrate more on commercial and industrial pursuits – many of the latter associated with the manufacture of woollen cloth. Agricultural productivity, urban and industrial growth, and the emergence of a monetized foundation for transactions were among the leading factors underlying economic development in medieval England.

Coinage came into existence as a mere intermediary in the process of supplying people with what they needed to live and work – that is, to facilitate commercial transactions – but in time came to acquire a pre-eminent significance, so that it was perceived not only as a tool for evaluating wealth, but as wealth in its own right. Yet England had few mines producing the precious metals which were desirable ingredients of coinage. It obtained those metals primarily through the process of commercial exchange that coins were designed to service, and the English commodity of exchange that was most in demand in other lands was wool. Despite its lack of precious metals, England was already one of the most monetized states in western Europe by the time of the Conquest, with a large number of mints operating in its southern and midlands shires, and national taxes being levied in coin.

Photo © S. Alsford

A Colchester hoard comprising over 14,000 silver pennies and other

coins, most buried in 1256 but with later additions in the 1270s. The hoard was found in

a lead canister buried in a property located on Colchester's High Street; another hoard,

of over 11,000 coins, had been discovered decades earlier on the same property, with a deposit

date of ca. 1237; another canister was later found empty in an adjacent property,

its contents presumably retrieved by its medieval owner. Such protective canisters are

unlikely to have been used by casual hoarders, but are likely to have been owned by someone

who dealt with money in a professional context. These large hoards of good-quality coins

(most unclipped) are suspected of belonging to a family of Jewish money-lenders, for

several stone houses belonging to Jews are known to have stood along that part of

the High Street. At that period Jews were being subjected to periodic pogroms (one in 1278),

culminating in their expulsion from England in the 1290s.

Currency control has always been one key preoccupation of the authorities of sovereign states, not least because coinage provides a more effective tool (than render in kind) for assessing and collecting taxes. As Anglo-Saxon England developed into a unified monarchical state, its kings, wanting a standardized coinage spread across their realm, set up mints in dozens of established cities and towns and in the newer burhs they were creating; this was partly because those locations were better protected, but probably also because commerce, which would serve to distribute coins more widely, tended to be concentrated there. Foreign currency entering the country was supposed to be melted down for re-minting in English form – mainly silver pennies; the name of the minter and the place where minted was to be put on every coin, as a guard against fraud, together with a stamp of the issuing authority as authentication.

Coins of known and reliable quality helped build confidence in commercial transactions, and were part of a broadening economic strategy that came to include: limiting major transactions to public places, notably towns; punishing those trading in stolen goods; provisions to improve the travel infrastructure (in terms of maintenance and security) – for the most regular travellers, traders, were key players in the distribution of coinage; and the imposition of standardized weights and measures. These – together with the early emergence of proto-urban commercial sites (wiks) and foci of artisanal enterprises (known as 'productive sites') such as pottery manufactures – were among the factors encouraging the growth of a money-based commercial network, even though that is unlikely to have been a conscious, or long-term, goal of the monarchy's policies. The increasing numbers of markets and fairs in turn stimulated demand for currency; whereas exchange between friends or neighbours might conveniently be done with barter goods, money provided a relatively neutral medium facilitating transactions between two otherwise unconnected parties, at least one of whom would be a travelling trader.

Most of these policies continued after the Conquest; although the number of mints had been reduced, and would be again during the twelfth century, they were still distributed fairly evenly across the regions, except for a large number in East Anglian towns – perhaps because of its relatively high population density and volume of trade. The monarchy was, on the whole, quite successful in upholding the weight and silver content of English currency and keeping foreign coins out of circulation, although finds of foreign coins at English port sites may point to them being unofficially accepted in payment there [John Schofield and Alan Vince, Medieval Towns, 2nd. ed. London: Continuum, 2003, 158]. Domesday's assessments of the fiscal value of English lands to their new masters seems premised on the assumption that the revenues due from places and people could be paid in coin.

By about 1300 "the amount of money in circulation had grown more rapidly than the population" [Christopher Dyer, Making a Living in the Middle Ages, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002, 101], correspondingly reducing the frequency of barter transactions, and a larger number within that population were becoming accustomed to carrying about the silver pennies in purses at their waists. Pennies remained the mainstay of the physical currency, although limited quantities of smaller denominations were minted and it was fairly common to cut pennies in half or quarters – suggesting the use of coins for transactions of all sizes, and further broadening the proportion of the population using coins as a routine medium of exchange for both goods and services. Edward I's coinage reform of 1279 put more emphasis on minting of halfpennies and farthings, and introduced the groat (worth 4d) to counteract foreign coins of similar value; it became more useful with the rise in daily wages following the Black Death.

Shortages of silver, and therefore coin, only became a problem in the Late Middle Ages; some debasement took place in consequence, though English currency was relatively stable. This stability, however, made it a target for clipping and counterfeiting, the latter declared treasonable by the Statute of Westminster (1275); anyone trading with coins not of the correct weight was likewise threatened with capital punishment – a prohibition that had to be abandoned around the close of the fifteenth century, as public suspicion of well-worn coins was interfering with the normal flow of commerce. Great efforts were made to prevent export of precious metals and circulation of foreign coins. In addition there was (from 1344) increasing introduction of gold coins, initially in the form of the florin; but subsequently the noble, worth 6s.8d. (half a mark), became the most commonly minted. However, there was not sufficient gold available to support a sizable gold-based currency.

Photo © S. Alsford

Gold coins from the Fishpool hoard oburied in Nottinghamshire

ca.1464. Most of the 1,237 coins were English nobles, half-nobles, or quarter-nobles,

though some were foreign. Hoarding contributed to shortages of bullion. From the reign

of Edward IV special gold coins, nicknamed Angels (because bearing the image of

the archangel Michael), were struck to augment cures believed to be effected by the king

via a ritual of laying-on of hands to victims of scrofula and other ailments;

the 'touch pieces' were given to the sick and, for efficacy, could be worn, medallion-like,

around the neck.

Pounds and shillings were still only a money of account, the penny being too small a unit for accounting purposes. For it came to be understood in the Middle Ages that coinage had two facets: an artificial or ghost facet, whereby money functioned as a standard for measuring value of real things (such as for the purposes of commercial exchanges or of tax assessment); and a physical facet, whereby the intrinsic value the metal in coins enabled them to serve not only as a medium of exchange but a means of storing wealth, so that coins were a commodity in their own right.

The latter was more tardily appreciated than the former and encouraged the accumulation of capital, which not only Catholicism but also Aristotelianism saw as an unnatural activity, for it changed money from a facilitator of trade to a goal of trade (i.e. profit, which risked usury and nurtured avarice). Some late medieval social commentators could express fear that love of money was becoming the focal feature of both culture and cult, rivalling love of God. The mid-fourteenth century friar and influential preacher, John Bromyard, referring obliquely and satirically to the standard silver penny (each of which bore an impression of the Christian cross) wrote that "He who has a purse copiously marked with the silver cross and always knows how to impart its abundant blessing can enter any court, and safely go wherever he wishes .... This cross conquers, it reigns, and it wipes away the guilt from everything." [cited by Diana Wood, Medieval Economic Thought, Cambridge University Press, 2002, 70]

Several slightly variant versions of this painting of a presumed married couple were

created by at least two different Fleming artists, the earliest in 1514; the above

extract is from one dating to 1542, and probably by Marinus van Reymerswaele. While

open to widely differing interpretations – the man is usually interpreted as

a money-changer, but alternatively as a money-lender, banker or tax-collector –

the painting can be seen as a simple occupational portrait (a genre then coming

into vogue) or a satirical/moral commentary. Be that as it may, here the artist

has eliminated some components of earlier versions in order, it seems, to focus

on expressing his subject's attitude towards money, which appearss to border

on love or even devotion.

The spread of coinage presented problems of coordinating the use of coins issued by different authorities, of varying weights and values, and so stimulated the development of banking; in the Middle Ages this was mainly associated with the more heavily commercialized parts of Europe, notably northern Italy. In England minters also engaged in money-changing, while others acting as money-changers were expected to re-sell to minters any foreign currency they purchased, so that it could be repurposed into English coinage; some of that foreign currency may, however, have been sold to persons intending to travel abroad. This situation still left room for problems and, in an effort to thwart counterfeiters, the Leges Henrici Primi explicitly restricted money-changing to moneyers, but whether this could be enforced in practice is doubtful. In Italy money-changers stationed themselves in marketplaces and along commercial streets, seated on benches (hence the origin of 'bank') – today's ATM machines might be considered a rough counterpart; it is unclear whether this was the case in large English cities, but certainly some moneyers appear to have been based on High Streets.

Money-lending was one of the few occupations open to Jews, because of the Church's strong opposition to Christians committing usury. Italian family companies got into lending in a big way to the English monarchy, but it also frequently called on English towns and merchants to make loans; some merchants voluntarily gambled large sums on the hope their loans would eventually be repaid and might win them royal favour or custom. Banking developed out of a combination of money-changing and money-lending. Initially, since changers needed secure facilities for holding the bullion they acquired, they accepted into safekeeping deposits of other people's valuables; from this it was not a long step to lending out a percentage of the funds they had on deposit. Deposits and loans were mostly associated with commercial activities. In England, however, the unsophisticated tools of credit transactions, the persistence of money-changing under royal control, through licensed agents, and creation of the Royal Exchange in the sixteenth century retarded the development of banking institutions, although merchant goldsmiths may have been active in illicit deals in bullion.

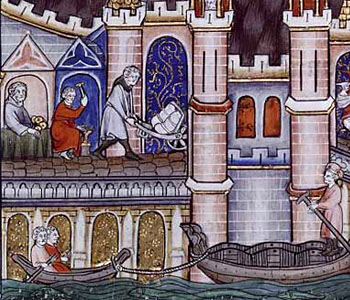

This illustration from an early fourteenth century French manuscript

La vie de Saint Denis shows services needed at quayside: the ubiquitous smith,

a porter for transporting merchandize, and a money-changer stationed in a booth.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des Manuscrits

The linked growth of commerce and coinage gave rise to ancillary occupations such as that of toll collectors. Tolls on merchandize are evidenced in England before it became a unified state. But this was essentially just a form of taxation. Only in the Late Middle Ages does it become evident that tolls or customs on international commerce were being used as a tool of proto-mercantilist economic policy, furthering economic nationalism, while trade embargoes were well-established as diplomatic weapons.

Although mercantilism is a concept generally associated with seventeenth-century economic thought, some of its ideas are perceptible in the Late Middle Ages. These included: a misplaced focus on accumulation of a stock of bullion/coinage, as the chief means of building the power and wealth of a sovereign nation, at the expense of that of others; efforts to transition from export of raw materials to export of finished products in order to create a more favourable balance of trade and avoid excessive emigration of English coin; grants of trading monopolies or other advantages to native merchants, in part through staple ports; and the development of maritime capability, if not (yet) control of the seas. The emergence of mercantilism was, however, premised on a shift in traditional attitudes towards commerce and commercial agents.