Since medieval illustrations of inns and taverns tend to depict only the more iconic features, it can be useful to consider later and earlier forms of such establishments, in terms of what we might expect to find in medieval counterparts. The thermopolia and cauponae of Ancient Rome, for example, typically needed some kind of kitchen facility and latrine, and it would be reasonable to posit the same in at least the larger medieval eateries, even though such are ignored by artists.

Although it represents a post-medieval establishment,

this reconstruction of the interior of a Louisbourg inn reflects aspects

of medieval alehouses too.

(above) Much of the floor-space is taken up with tables for the general public.

(below) But smaller tables were available for parties wanting a little privacy.

Photos © S. Alsford

The original on which the museum reconstruction is based was owned by a retired soldier Julien Auger dit Grandchamp (1666-1741) and later operated by his widow. It was a modest establishment located near the quayside and catering largely to travellers, sailors on shore leave, and perhaps (in regard to drinking) members of the colony's garrison. For purposes of interpretation, the museum reconstruction shows it better endowed with furniture and equipment than would likely have been the case.

The interior comprised a single public room, about 24 feet wide and 19 feet deep, that provided for consumption of alcohol (wine, cider, liquor, locally-brewed spruce beer) and of food cooked over the hearth, for socializing (exchanging news, business transactions, games such as cards, chess, or checkers), and for overnight accommodations beside the hearth, in the kitchen at rear, and in the garret – an inventory taken at the time of Grandchamp's death included seven blankets and eight mattresses and bolsters, the most valuable of his possessions. The centre of the room had large tables, at which patrons were accommodated on long benches; smaller tables in two of the corners accommodated diners and games-players, seated on chairs or on stools made from empty barrels. Drying herbs were hung from some of the ceiling support beams. Pewter and pottery jugs and mugs were arrayed along the mantelpiece and and a shelf. A large cupboard on the other side of the fireplace held crockery and cutlery for diners, as well as gaming boards and accessories. The brick fireplace has a large cooking-pot hung over the hearth; soot stains on the wall above the fireplace show that not all smoke escaped through the chimney. The innkeeper and his wife themselves lived in an adjacent house.

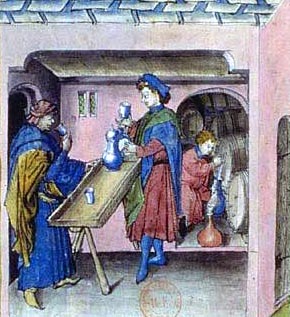

From a copy of the Tacuinum Sanitatis in the

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des Manuscrits

(above) Wine is drunk in a tavern that evidently caters

to a better class of customer, while the taverner, in a back-room, fills another jug.

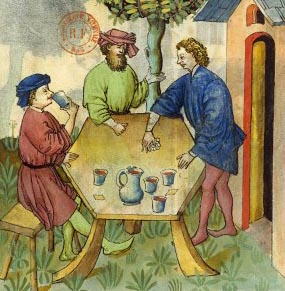

(below) Innkeeper George Starcz (d. 1470) is depicted, at left, serving food and drink

to four male customers gathered around a table (covered with tablecloth); two of them

wear spurs, indicating that they are passing through, not staying overnight. A plate

of what may be roast chicken sits in the middle of the table, and pieces of bread are

also present, along with small plates. Beneath the table a pitcher is being cooled

in a tub of water.

.

From the Hausbuch der Mendelschen Zwölfbrüderstiftung

Medieval depictions of tavern or inn interiors generally show customers drinking and/or the proprietor filling a jug with ale or wine. Occasionally other tavern activities are shown.

(above) A group of drinkers plays at dice at a table outside

the tavern entrance.

(below) Drunkards arguing at a tavern.

From a copy of the Tacuinum Sanitatis in the

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des Manuscrits

Illustrations such as those above reflect the types of activities associated with drinking establishments in all eras. For instance, a group of four frescos decorating the interior of the caupona of Salvius, at Prompeii, depicts a man and woman kissing, drinkers being served by a bar-maid, dice-players, and brawlers being ejected by the manager. There seems to be an element of conflict in each of the scenes, though whether they are intended to be humorous or to warn patrons against frowned-on behaviours is not clear.

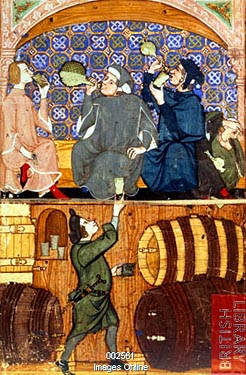

This oft-reproduced depiction of a tavern interior is from a fourteenth century copy

of a treatise on the vices written by a Genoese man for the instruction

of his children. The cutaway view appears to show patrons drinking in a ground-floor room,

while the taverner collects more wine from tuns stored in a cellar.

British Library

In illustrations that show the taverner collecting wine and patrons drinking, the former usually seems to be within sight of the latter. This may reflect a common concern about possible frauds on the part of taverners, mixing old wines with new. The London authorities prohibited blocking patron access to the storage area (such as by a door, or a sheet hung across a doorway), so that patrons could, if they wished, observe the drawing of wine. Efforts were also made to restrict the number of taverns authorized to sell sweet wine; a pair of Genoese operators of a London tavern, apparently on behalf of the prominent Genoa family of Spinola, tried to circumvent the problem by having separate cellars for sweet wines and non-sweet and, when the city authorities objected, obtaining royal approval for an exception to be made on condition the proprietors swore an oath not to mix the different types of wine. It must have been concern about mixing that prompted the 1370 ordinance forbidding taverners from retailing new wine until any old wine had been removed from the cellar.

George Semler (1512-1580), landlord of a tavern probably known as the White Eagle

(to judge from the sign on the wall) is depicted in the window-lit cellar where

he stored his barrels; he is evidently drawing wine or ale, and atop one of the barrels

is a mug that will allow him to taste-test the quality of the drink. A blackboard hung

on the wall, with candlestick to cast light on it, may have been used to keep check

on his stock. Steps lead up to the street.

From the Hausbuch der Mendelschen Zwölfbrüderstiftung

The cellar was often not simply for storage of butts but the location of the tavern itself. Any wholesale dealer needed a cool place to store wine and ale for at least brief periods and the cheaper option in the long-term was to acquire or build a house with a cellar, or undercroft. If well planned, with proper walling, lighting, and access from the street, the cellar could easily be used for retailing drink. Although limited to those wealthy enough to afford them, undercrofts were becoming fairly widespread in English towns by mid-twelfth century, except in terrain close to the waterline (and a few are found even on such sites). Initially they were integral components of houses, whether stone-built or wood-built (in the latter being lined with planks); during the Late Middle Ages, however, they were usually separately built elements, with the upper structure of wood atop the stone-lined cellar. Use of stone was not just to create a sturdy and level foundation to support multi-storey houses above; it also offered greater protection from fire or break-ins and therefore appealed to vintners and other merchants (whose wealth was in their merchandize), as well as to moneyers and Jews.

(above) This stairway down from street to subterranean doorway

hints at what the entrance to a medieval cellar tavern looked like. It is part of

a stone building in Church Square, Rye, that became a private house in 1307 (possibly

having been an extension of a friary dissolved in that year) but largely rebuilt

in 1898.

(below) Stairway into a Winchelsea cellar. Being entirely below ground level,

Winchelsea's medieval cellars did not often have windows, so the doorway might

be the main source of natural light. Upper steps of cellar stairways typically

projected into the street, as did light-wells for windows, where they existed.

Photos © S. Alsford

When New Winchelsea was founded in the late thirteenth century, the construction of new homes and businesses for the relocated townspeople included providing a number with cellars; they were necessarily built before houses were erected atop them, suggesting that most date from years following official handover of the new town (1288) to the townspeople. Some fifty cellars are known to have existed, although it is uncertain whether this represents close to the total number that were dug; certainly cellars were costly to build, especially when vaulted, and only those of the wealthier burgesses of Old Winchelsea who needed them would have made the investment, although some may not been thinking of personal use but of renting them out to others for wine storage or as a shop or tavern; in that regard we may note that the great majority of urban secular undercrofts had no direct access from the house above. Of the known Winchelsea cellars, thirty-three remain accessible today – one of the largest surviving concentrations in an English town and material testimony to the one-time prosperity of the town [they are discussed in detail in David and Barbara Martin's New Winchelsea, Sussex: A Medieval Port Town, Kings Lynn: Heritage Marketing and Publications Ltd., 2004, ch.9].

These cellars almost all happen to be in the northern part of the town, closest to the medieval harbour and quayside (though not itself near water level). Although this may be partly due to losses in other parts of the town redeveloped as Winchelsea's economy declined and its populated area contracted, it also owes much to the likelihood that such cellars, vaulted for added strength and to improve their appearance, were used for storing goods imported and exported by ship, particularly but not exclusively wine. Wine needed a cool environment if it was to be stored for an extended period, and Winchelsea's cellars could provide a consistently cool temperature (although dampness made them less suitable for some types of goods, such as the more delicate textiles); while wine intended for prompt shipping to other English locations may have been held in warehouses near the harbour, that to be sold by retail in the town or shown to regional buyers, who might transport modest quantities by road, would have been moved to cellars. We know that in 1296/97 the king was hiring cellars, in which to store wine purchased for his use, at the quayside and from members of the Alard family. By contrast, the kinds of goods sold in the marketplace and its vicinity, at the southern end of town, are less likely to have required cellar storage, and the few cellars nearer the market area were not vaulted.

While storage may have been the function of cellars lacking windows and other client-friendly features, and the part-function of some of the others, it seems most probable that a number of Winchelsea cellars were doubling as mercantile showrooms or taverns. This seems particularly likely for those on corner plots; entrances directly off the street (although this represents the majority), decorative architectural features, and windows (via light-wells), are also indications of public access. This category of cellars tended to have their walls plastered, which would also have improved the appearance and distributed light better; that the fifteenth-century undercroft of the White Swan in Norwich had decorative paintings on its walls is a sure sign it was not being used simply for storage. Almost half the Winchelsea cellars had recesses built into the walls, acting like cupboards, many showing signs of accommodating covers or doors, and some of a shelf. In only one, however, has a fireplace been discovered; but that, perhaps significantly, in the front bay of a three-bay cellar. These commercial-use cellars were probably operated in most cases by local merchants, but some may have been rented out for brief periods to Gascon vintners, who frequented Winchelsea in large numbers, selling some of their wine on the spot, but moving most to London or other locations.

Taverners and vintners are likely to have been predominant among the local operators of the commercial-use cellars, and some were almost certainly taverns where drink was consumed by purchasers. The spacious cellar of the Salutation Inn, divided into three bays, is a good candidate for this kind of use, with storage where it could be coolest in the rear bay (or perhaps further back, as there was a doorway, now impassable, at the far end) and customer service in the other two, the central one perhaps more private than that immediately beyond the entrance. The doorway in the dividing wall would have given potential for visual access the law demanded of taverners when drawing wine from a cask, while the series of recesses could have held drinking vessels.

Cellar of the Salutation Inn, Winchelsea.

Photo © S. Alsford

The cellar under the Salutation Inn is one of the larger surviving ones in Winchelsea, running across what were two adjacent plots in the original layout of the town; the larger of those plots was a corner property and the cellar's entrance was at the narrow end facing onto Castle Street. The longest of Winchelsea's cellars, it is an unusually elaborate one (the ribs of the vault have corbels sculpted into decorative figures, and the arched doorway is moulded) and a comparatively well-lit one thanks to window-wells along the Mill Road side; its relatively wide entrance stairway was flanked by its own low walls capped with handrails.

Though none of the plots allocated in the original town layout were assigned to corporate groups, the earliest known use of this site was as a hospice run by the Franciscans – that is, an inn, known as the Salutation of the Angel and Our Lady of the Grey Friars; it was not close to the friary site itself, but did not need to be, for its purpose was to accommodate visitors, mostly pilgrims, many of whom passed through Winchelsea's port en route to or from the continent. It was located in the corner of the hilltop settlement close to the road down to the port. This building was certainly operating as a tavern by the seventeenth century, and probably well before that, retaining 'Salutation' in its name; the characteristics of the cellar strongly suggest it was built for, or adapted to, a tavern function. The timber-framed buildings atop the cellar, rebuilt in the fifteenth century, suffered bomb damage in 1943 and now are used as cottages that still include 'Salutation' in their name.

The cellar of the building now known as The Retreat has similar characteristics

to the Salutation, although smaller and less elaborate; it too is a corner property,

with its entrance off the High Street. It might have been used as a tavern or

a shop/showroom in the fourteenth century. In the fifteenth the timber-framed house

above was rebuilt and a shop was incorporated on the ground floor, interconnected

with the cellar.

Photo © S. Alsford

The famous Chester Rows also began life as buildings combining domestic and commercial uses. They are characterized, in their earliest phase of construction, by semi-subterranean undercrofts, whose often elaborate structure suggests public access, topped by lock-up shops, selds, or residential rooms. Some of the undercrofts had stairways communicating with the upper storey and may originally have been for commercial use by residents. But others had no such communication, or show signs of having been sub-divided into multiple spaces, suggesting the operators of the commercial establishments were not necessarily residing above; over the course of time, ownership of some of the undercrofts became separated from ownership of the residence above. As with the Winchelsea cellars, the Chester undercrofts relied primarily on the entrance door to provide natural light.

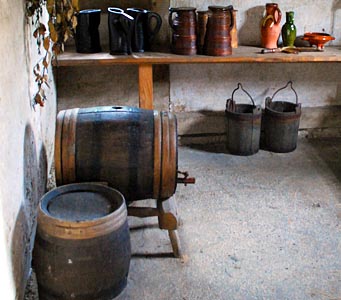

Many taverns would doubtless rely on fairly plain vessels and utensils, such as

the barrels, jugs, and tankards seen above (detail of the early sixteenth century

buttery of the Bayleaf farmhouse at the Weald and DOwnland Open Air Museum).

However, some better-quality items may have been in the inventory of taverns catering

to a better class of clientele. The thirteenth or fourteenth century tripod pitcher

(below left) would have been appropriate for use by a taverner collecting wine or ale

from a barrel before dispensing it to customers; housewives may have owned something

less decorated to buy supplies of ale from brewers. The early fourteenth century

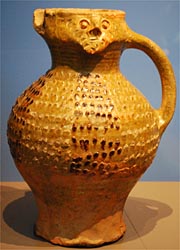

face jug (below right), produced on a rural kiln at Grimston (near King's Lynn),

portrays a bearded man whose nose dripped when the jug was poured (probably not intended

to parody any particular person); such jugs were fairly common and may have

provided amusement to groups of tavern customers sharing a jug of ale.

Photos © S. Alsford

|

|