The battle of Hastings came down in tradition as a victory of cavalry over infantry, although in fact the role of William's archers was at least as important as that of his knights. Anglo-Saxon armies seem to have included a few archers, but firing individually rather than in massed volleys. If Harold's force had included archers when he headed north to meet the Norse incursion, it seems that in his haste to return south to halt the Norman advance he left them behind.

The Anglo-Saxon shield-hedge, well-placed on an uphill slope, had proven impenetrable to the Norman cavalry, until one or more feigned retreats had led some of the defenders out to their deaths, and then William followed this up by having his archers, whose earlier volleys had been stopped by the shield-wall, shoot arrows in an upwards arc, to come down on the troops to the rear of the shields. This fire, which also claimed Harold among its victims, thinned out the defenders and enabled fresh cavalry assaults to finally break the Anglo-Saxon line. The lesson does not seem to have been fully appreciated. however, for reliance continued to be placed by the Normans on their cavalry.

Artist's rendition of the use of archers at Agincourt,

situated behind a row of stakes to protect them from those charging knights

who survived the hail of arrows.

Foreign wars helped bring archers back into the picture. the shortbow, used by the Normans at Hastings, had remained the standard down to the twelfth century, although the crossbow was gaining ground on it. Henry II's Assize of Arms made no mention,however, of bows as one of the requisite weapons, ignoring as a whole the lowest ranks of manpower who could not afford proper equipment. In their war with the Welsh, the English encountered contingents of longbowmen and also the tactic of holding off knights by planting spears in the ground, angled so their heads pointed at the charging horses' chests. These two elements were combined by the English in what proved (once there had been learned the additional lesson of protecting the archers with pikemen or the lances of dismounted knights) an effective defence against heavily-armoured cavalry.

Consequently, the bow was listed in a revised edition of the Assize of Arms issued in 1252 and made obligatory for men of the 40s. level of wealth. During the reign of Edward I, bowmen began to beome an important auxiliary force within the army. Englishmen of the non-chivalric classes were later (1363) ordered to spend their Sundays and holidays in archery practice rather than on sports without military value. Use of the longbow required strength, particularly in the back muscles, and a high level of skill that involved not just individual accuracy, but the ability to work with other bownmen as a unit. It might take years to acquire the skill and and adapt muscles and skeletal structure to the task.

Orders to practice appear to have met with limited compliance; this may have been particularly true in towns, where there were many other recreational distractions, although it appears to have been common for communities to designate some uninhabited area on the edge of town for archery and/or crossbow practice, and Edward IV made this official, when ordering practice at the butts to take place on every feast-day. At Coventry the craft gilds were instructed to set up butts for their own members. At Warwick, a road still known as The Butts, situated just inside the line of the town wall, carries a memory of the use of this area for target practice.

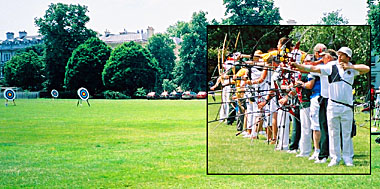

(above) Artist's rendition of archers practicing

shooting at butts. (below) Even today target practice can be

encountered in public spaces (here, in London's Kensington Gardens)

Composite photo © S. Alsford

Despite the need to repeat periodically the orders to practice, which suggests some laxity, a body of skilled longbowmen developed across the country, and particularly in the Marches where conflict was more common. They were able to fire up to ten or twelve arrows per minute (a much faster rate than crossbowmen could achieve, and the longbow was much lighter to carry) with high accuracy to a range of about 250 yards. The best archers came from the frontier regions, where conflict was more common. In the towns, archers were not restricted to the lower echelons of society; Norwich muster rolls from mid-fourteenth century, for instance, show a painter, mercer, tailor, and goldsmith taking that role.

Longbowmen taking part in a re-enactment of

the battle of Tewkesbury (1471).

Photo © S. Alsford

The longbow was not unknown in England before the thirteenth century, but strategic use of massed longbowmen to help break up cavalry charges was something new. It was the sheer scale of attack, with wave after wave of arrows falling, that was devastating. At Agincourt, over 80% of Henry V's army were archers. His strategy might have been inspired by a similar slaughter inflicted on Englishmen at the Battle of Shrewsbury, where hostilities opened with barrages of thouands of arrows exchanged between Prince Henry's and Harry Hotspur's forces, one chronicler claiming that the flights of arrows were so thick they blotted out the sun. The prince had himself been wounded by one of the arrows. However, this opening gambit, a precursor to the artillery bombardments of post-medieval conflicts, had in fact long been a standard tactic, aimed at softening up an advancing line or fragmenting a tight defensive formation before the infantry joined battle.

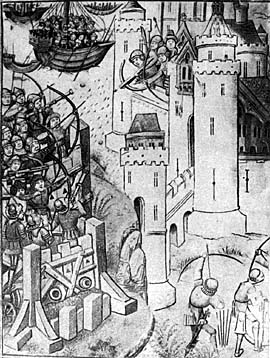

This depiction of Edward III's siege of Calais,

by land and by sea, shows that it was not just on the field of battle

that archers had an important role to play.

A slow but growing use of firearms gradually displaced longbow and crossbow, although in England, where adoption was slower than some other countries, they were used side.by side in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Archers had greater accuracy over longer range and could fire at a more rapid rate than gunners, but improvements in firearm technology eroded the advantages of traditional weapons.