Urban gateways served a number of purposes other than defensive. Indeed it might even be suggested that defence was not their primary purpose: that they were points at which fortified enclosures were penetrated by access routes and special accommodation was required to enable access while avoiding compromising the protective role of the enclosure.

The original sense of "gate" was not a barrier, but rather a means of access. The term "bar" was used to refer to barriers placed across roads into a town; when gateways were constructed they sometimes supplemented, sometimes superseded earlier bars (and, in the latter case, might retain that designation). Some early gates may have combined bars and stone archways spanning roads passing through an earthen bank or wooden palisade; multi-storey gatehouses equipped with heavy wooden doors or portcullises represent a later phase of development.

The south face of the main gateway of the

Priory of St John of Jerusalem, Clerkenwell parish, London. (built

1504, but much restored in the nineteenth century) The relatively

modern bollards blocking vehicular access through this gateway

are a simple device reminiscent of medieval bars.

Photo © S. Alsford

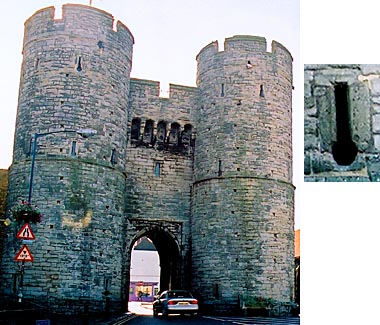

The The West Gate at Canterbury is one of the more impressive urban gates to have survived in England, and a good example of a gateway built with defence in mind. The gateway proper, equipped with portcullis, is flanked by two drum towers, which have loops to accommodate hand-guns, distributed across their front, divided up among the three storeys. Guns are known to have been stationed there by 1404.

There had probably been a gateway on the site since Roman times; a late Anglo-Saxon chapel had been built atop it and later acquired the status of a parish church. Three other city gates (Burgate, Northgate, and Ridingate) were also architecturally associated with chapels or churches. Canterbury's west gate straddled the busy road coming from London, and the street stretching outside it was lined with inns to serve pilgrims, particularly those who arrived too late at night, after the gate had been locked shut. What is now roadway immediately in front of the arched passageway was originally a bridge (part drawbridge) over the River Stour.

The present structure, was built in the context of fears of French invasion. The old gate was pulled down in the late 1370s (the church above it relocated nearby) and the new one completed by 1381. It was financed in part from local taxation and partly by Archbishop Sudbury, who was killed later that year during the Peasants' Revolt. His gate and the other city defences had not prevented the rebels from entering the city, where they ransacked the castle, freed prisoners from the city gaol, burned records, forced the local authorities to swear allegiance to King Richard and the Commons, executed a few residents they considered traitors, and looted the archbishop's palace. By contrast, in 1450 Cade's rebel force was obliged to wait for three hours outside the West Gate before the mayor finally communicated a refusal to open the gates to them.

the Canterbury's Westgate. (above) The exterior (north) face, with

inset showing one of the inverted keyhole punports. (below) The side

facing into the city.

Photos © S. Alsford

The facade visible from within the city has a quite different character to that facing outwards: less militaristic, more civic. For many years the gate was part of a civic ceremony in which the mayor and other members of city government made a procession to the tomb of Archbishop Sudbury, to hear prayers said for the soul of their benefactor. In 1473 the king authorized the city to use the interior space as a gaol, as which it continued to serve up to 1829 (which may explain its survival), as well as a place for hangings.

One of England's leading master masons, Henry Yevele, was a consultant on Canterbury's Westgate project, and may even have been the design architect. A citizen of London (1353), he served as one of the wardens of London Bridge 1368-83 and was probably the architect of the chapel erected atop the bridge in the years that followed. He was employed from about 1359 on by various members of the royal family, on works at the Tower of London, Westminster Palace, and elsewhere. He also had contracts to work on castles in Kent and at Southampton and Winchester, and was evidently familiar with current trends in fortification design. He was engaged in work at Canterbury castle when approached to participate in the Westgate project. He subsequently rebuilt the nave of Canterbury cathedral (having already produced the high altar screen for Durham cathedral). Yevele also had a reputation as a tomb designer, and was responsible for those of Edward III, the Black Prince, and Archbishop Sudbury. He was acquainted with Geoffrey Chaucer, whose clerical services he had engaged on one project.

Like the west gate at Canterbury, that at Warwick also had a chapel built atop it (altered somewhat by nineteenth century renovations) and was also the place where hangings were carried out. Warwick's high street is bounded at east and west ends by gates. The east gate also had a chapel built above it, but not until the 1420s, after a parish church with the same dedication in the high street was taken down; the gate may have been rebuilt at the same time. The chapel was later rebuilt as a school.

Placements of chapels above gates may have been to benefit from offerings from pilgrims passing through and from townspeople returning safely from journeys outside. However, gateways into Anglo-Saxon burhs seem particularly associated with religious facilities, and this may have been for a different reason, just possibly a notion that it might foster divine protection.

Two views of the West Gate at Warwick: (left)

the main entrance on the west side; (right) the east side, facing into

the town. The gate was built into solid rock at its base. The chapel above

it was in existence by the mid-welfth century, and architectural evidence

points to the gateway arch having existed at the same period. But the whole

structure may have been rebuilt by the earl in the late fourteenth century,

since his arms were placed on the chapel parapet. In the fifteenth a tower,

with belfry, was added at the west end, with the gateway passage extended

through it. The east window and the flying buttresses on the south side

are post-medieval additions. A guildhall was built next to north side of

the gate in the late fifteenth century and in the following century became

the meeting-place of local government.

Photo © S. Alsford

In 914 Ehelfleda, the ruler of Mercia, raised a burh on a knoll on the north side of the Avon, now the centre of Warwick; the burh protected part of a settlement that was probably a proto-town ("wick" indicating trading activities) and administrative centre of a royal estate. It was one of a number of burhs she established as the Mercian counterpart of the Wessex burh programme of her brother Edward the Elder. William the Conqueror had a castle erected within the burh fortifications in 1068 and, later in the century, a ditch was dug around the ramparts (perhaps only enlarging a ditch associated with the burh), with gates providing access into the settlement.

A roughly circular town wall was later constructed (date unknown), apparently between the ramparts and the ditch. Murage grants were received by the earl in the early fourteenth century, but may relate only to maintenance. In addition to east and west gates, Warwick also had a north gate, but it was later taken down; the bridge over the Avon probably had some kind of barrier that allowed it to act in lieu of a south gate. The town wall had been demolished by the sixteenth century. Warwick was situated fairly far from England's at-risk frontiers and defensibility may not have been a high concern, particularly with the strong castle within the town. Although there are indications that gates were installed at either end of the long tunnel between the front and rear arches, the West Gate does not seem to have been built with defence as the primary preoccupation.

The self-consciously impressive Bargate at Southampton now occupies a spot in the modern town centre and is detached from the walled circuit, so it is hard to imagine that it was the medieval town's north gate. The gate developed in phases. In its original form (ca.1175) it was little more than a stone arch with a short, plain tower over it, similar to the town's West gate. The town ditch in front of the gate was spanned by a bridge, and on either side of the gate the defences were still of the ramparts/palisade type. In the late thirteenth century, the ramparts were replaced by a stone wall, drum towers were built on either side of the gateway, and a hall built above it, with the south front added at this time or a little later, for use by local government. In the early fifteenth century the north side facade between the towers was rebuilt into a front projecting out over the original gateway; it was furnished with battlements (with machicolations) and buttresses, with a view to improving defensibility, including housing (or perhaps relocating) a portcullis. Various local tolls were collected at the Bargate, including one for crossing the bridge.

Like Canterbury's West Gate, Southampton's Bargate presents different

aspects on the exterior, north side (above) and the south side (below)

facing into the town. The south side shows more clearly the extent of

the guildhall above the gateway; it continued in use for aspects of

civic administration up until the 1930s. The large central archway and

the two smaller ones existed in the medieval period, the mid-sized pair

immediately flanking the main arch being later insertions. The

present windows are Victorian restorations of medieval features.

Photos © S. Alsford

The decorative elements of Bargate are also post-medieval, yet indicative of a late medieval trend towards using town gates to display civic symbols indicating the sources from which local government derived its authority or the community its identity.

The heraldic shields above the south side archway are the crests of families prominent in town government in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, flanked by those of two saints, but could conceivably have been preceded by other crests in the fifteenth century. A royal coat of arms positioned above them was removed in 1852. The two metal lions flanking he archway replaced an earlier wooden pair (probably sixteenth century) that stood at the far end of the bridge; they were part of one of those town foundation legends that were in vogue in the Late Middle Ages and were originally accompanied by painted tower-hung panels showing characters from the same legend.

The statue on the north side of the gate is of George III, but was preceded by one of Queen Anne, which itself presumably replaced something older; likewise, the statue of Edward VII over the archway of the North Gate in Salisbury's high street was preceded by one of Charles I and the niche is suspected to have held one of Henry III earlier. The sun-dial above the statue on the Bargate was installed in 1705, while the warning bell was put in place a century earlier. But again both features are in accord with purposes to which urban gates were sometimes put in the Late Middle Ages.

(above) Micklegate Bar at York, exterior face.

As the entrance for travellers from London and the south, this gate

conveyed an initial statement to many visitors. Initially a simple

gateway set into the earthen rampart, ca.1196 royal permission was

obtained to build a house over the gate. In the second half of the

fourteenth century it was heightened to enable a portcullis to be

installed, and a barbican was built in front of the gateway.

(below) Statues topping Bootham Bar represent a fourteenth century

mayor, a mason, and a knight, symbolizing the importance of

administrators, builders, and protectors to the wel-being of the city.

Quite a different message was given by the display, from Micklegate Bar,

of body parts of executed traitors (here remembered in a display in the

museum now housed inside the gate).

Photos © S. Alsford

All four of York's main gateways were, likely by the close of the Middle Ages, decorated with heraldry and statuary. Although many of the versions now adorning the gates are post-medieval replacements, they may well be reasonable copies of the originals. Micklegate Bar displays, between its pair of bartizans, two shields bearing the city arms, flanking a shield with the royal arms, over which is a helm with a lion crest; the form of the latter items is dateable to the late fourteenth century. Statues atop the battlements were in place at some time before 1603, by when sufficiently deteriorated that one needed replacing and the others re-painting. A statue of Ebrauk, legendary founder of York, once stood in a niche in Bootham Bar, though whether this was the same statue recorded as standing in the fifteenth century at a parish boundary, and later relocated to the entrance into the Guildhall grounds, is not known.

York's gates (except Monk Bar) were originally open-backed, with timber fittings in their interiors. They are examples of the adaptation of interior spaces in such structures to civilian uses. The most conspicuous instance, although post-medieval, is at Walmgate Bar where, probably in the 1580s, a small two-storey lath and plaster house was built into the city-facing facade. Similar treatment was given at the same period to Micklegate and Bootham Bars. These residences yielded rents into the city coffers. Walmgate Bar's house was occupied into the twentieth century; but even before it was built the city was, in the fourteenth century, earning rent from residents of rooms within the stone gate.

Walmgate Bar, inner face, showing the

hettied house (with support columns and balustrade) built into

the stone gateway.

Photo © S. Alsford

In contrast to major gateways, some of which are exemplified above, smaller gates, such as posterns, rather than playing any significant role in strategic defence or, toll-collecting, or ceremonialism, may have served the access needs of particular neighbourhoods, communities, or clienteles. One instance being a gateway at Norwich providing for as close a connection as possible between the extra-mural area and the swine market, thus minimizing the passage of pigs driven through city streets.