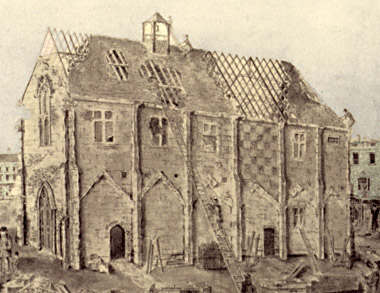

The Bishop's Guildhall in Salisbury was

probably built in the early fourteenth century. Here we see

its demolition in 1795 (because ruinous); the current guildhall

stands on the same site.

Extract from a watercolour in the Salisbury Museum,

artist unknown

The administration of justice at New Salisbury was in the hands of the Bishop, and consequently it was his court that convened in a guildhall in the south-east corner of the marketplace; he also later had a prison there. His seigneurial powers were exercised by his bailiff. Local self-government was probably spearheaded by the merchant guild, but a mayor was being elected by the early part of Henry III's reign. The bishop conceded a power-sharing state of affairs, through an agreement with the citizens in 1306, giving official recognition to guild and mayor; the bishop retained sole jurisdiction over judicial administration, but the presence of the mayor was required for judgements to be passed.

The communal administration had control over market, trade and other commercial matters, maintenance of the fabric of the town, and taxation. A group of 4 ward aldermen assisted the mayor, but governmental assemblies appear to have been open to all citizens. A council of 24 is seen by the close of the fourteenth century and was supplemented by a second of 48 representatives ca.1445; the two councils constituted the effective assembly. Although not until the sixteenth century do we hear complaints that others were shut out of meetings, attendance at most meetings rarely exceeded the councillors and city officials.

The meeting place of the communal assembly possibly varied during the fourteenth century; St. Thomas' church may have been one location, for the common chest was housed there in 1414. In 1416 we first hear of the Council House near that church. However, the Bishop's Guildhall and city churches were also used in following years for assemblies expected to draw larger attendance; St. Edmund's was usually the location for electoral assemblies. The Council House was used for more routine meetings of the administration, as well as for housing the archives and treasury, and presumably related bureaucracy.

The 'old town hall' in Northampton's marketplace.

The external staircase and the style of the windows are suggestive of a

medieval date. The building was one of the few to survive the devastating

fire of 1675, with the exception of the staircase, but was pulled down

in 1864 after a new town hall had been built.

Northampton's guildhall was large enough to accommodate the weekly meetings of the portmoot (or husting court, as the royal charters had it, modelling Northampton's liberties after London's) and of the town council, but popular assemblies for purposes of elections or the promulgation of important legislation were by 1300 summoned to meet in the larger space of either St. Giles' churchyard or the church interior. The guildhall in its earliest form probably comprised a two-storey structure, with the hall on the upper floor and the ground floor originally an open area, where stalls could be erected under shelter. Helen Cam [Victoria County History of Northamptonshire, (1930), vol.3, p.36] has suggested the third storey may have been added in the 15th century when assembly meetings began to be held there in the 1490s.

In 1467 efforts were made at Leicester to control unruly behaviour at communal assemblies, by banning non-freemen from such meetings and prohibiting those who were permitted to attend from yelling out nominations at elections [see Rules for orderly procedure at elections]. This did not resolve the problem, however. In 1489 parliamentary acts instituted both there and at Northampton a representative lower council of 48 burgesses to substitute for the assembly in the role of approving legislation and electing officers. The act for Northampton refers to disputes over elections, noting that

a large number of the residents, lacking in means or social graces, as well as in gravity, judgement, wisdom or sense, who have often outnumbered in their assemblies other persons of proven gravity, judgement and sound behaviour ... have through factions, confederacies, and noisy and unruly behaviour in those assemblies caused serious trouble, division, and discord amongst their number, at the time both of elections and of the assessment of lawful levies upon the community, to the subversion of good rule, government, and traditional politics, demeaning to the borough and often resulting in a serious breach of the king's peace...

[C. Markham, Records of the Borough of Northampton, vol.1 (1898), pp.101-02 (my modernization)]

The town council subsequently set out how elections would be conducted, henceforth in the privacy of the Guildhall, able to contain the reduced electorate, in an orderly fashion with as little noise as possible (votes being tallied in writing, rather than through acclaim or physical indications). In the 1490s this was followed by legislation setting punishments for seditious or slanderous talk against the administration, and for disobedience to mayoral orders.