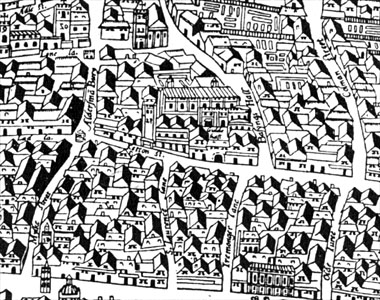

Extract from Ralph Agas' plan of London, ca.1560/70,

showing the Guildhall at centre, with the major thoroughfare of

West Cheap at bottom.

London's principal civic structure has been referred to as a guildhall since the twelfth century. Yet there is no evidence London ever had the type of merchant guild that, in many other towns, was instrumental in nurturing communal interests and ambitions for self-government. It has been suggested that the term might, in some instances, have derived from the payment of taxes ("geld") there [The Official Guide to the Guildhall, Corporation of London, 1992, p.5], or that it reflects the conviviality and mutual support aspects of guilds in general [C. Brooke, London 800-1216: The Shaping of a City, London, 1985, p.280]. Probably the interests that worked together towards establishing community-based government and exerting control over commercial and other matters of concern and benefit to the citizens, prior to the emergence of the mayoralty, created a sufficiently apparent and defined alliance of leading townsmen to warrant the application of the term "gild", which was loosely applied to all sorts of medieval associations.

As in much else, medieval London stood apart from other English cities in the size and grandeur of the seat of local government. The present building was constructed between 1411 and the 1430s. Its Great Hall is 152' long by almost 50' wide. We hear of a Greater (or Upper) Chamber and an Inner Chamber; in these rooms mayor and aldermen, or occasionally the full council, might meet in private or hold court sessions other than the husting. A library was built to the south, while east of the porch an existing chapel was rebuilt on a grander scale.

The west end of the Guildhall, above the

modern arcade, essentially looks much today as it would have in

the 15th century.

Photo © S. Alsford

Financing the construction of the "New Work", as it was called, relied

partly on private donations and legacies. But the initial enthusiasm

had diminished by 1413. The authorities were dismayed:

"God forbid that this, the most noble of cities, and

one which has flourished with every kind of honour more than all other

cities, could not suffice to continue, perfect, or finish, a work like

this, when once begun" [H.T. Riley, ed.

Memorials of London and London Life, London, 1868, pp. 590-91.].

They created a special fund for a six-year period, built from

increases in certain revenues:

And by redirecting existing revenues

At the end of this period (1419), other revenues were assigned to the New Work. There continued to be private contributions, such as money from ex-mayor Whittington's will; his executor, town clerk John Carpenter, chose – whether on the basis of oral instructions, an interpretation of Whittington's general wishes, or Carpenter's personal inclination, we do not know – to provide glass for the windows and marble for the floor, as well as funding the creation of the Guildhall library. But it was not until 1439 that the work was considered essentially complete.

An impressive entrance porch to the Guildhall

was erected between 1425 and 1430; the interior still has its medieval

features, but the exterior was remodelled in 1789. The facade of the

original incorporated statues representing civic virtues.

Photo © S. Alsford

Even the predecessor to the fifteenth-century Guildhall must have been a sizable building, capable of holding a large crowd. On February 21, 1347 we hear of an "immense number" of citizens who were assembled there when were chosen 133 men, divided fairly evenly among the 24 wards, to attend civic meetings when summoned, so as to represent the community in dealing with city business – this presumably meant the endorsement or rejection of decisions reached by the city executive and aldermen. There is a reference to a group of 40 citizens drawn from the wards in 1285 to assist the aldermen in this fashion, but the principle of representation in a city with a population as large as London's might have stretched back even further.

These ad hoc steps towards developing representative instruments of government produced a Common Council that by 1376 was meeting regularly. There were those in the city who wanted to break the mercantile grip on power by having this council drawn not from the wards, but from the craft gilds. On a couple of occasions their influence in government was sufficient to have such a measure put into effect; the change was short-lived.

The Great Hall (looking towards the dais) remains

the location of elections of London's mayor and sheriffs and of

the inauguration of the new mayor. Walls and columns are mostly original,

but the arches supporting the roof may originally have been of oak, rather

than the stone of today.

Photo © S. Alsford

Reform of the Common Council was one feature of the government of

John Northampton in the early years of Richard II's reign (see "Party

politics lead to civil disorder"), and was reversed when the patriciate

was able to engineer the overthrow of his faction. The mob politics of

such radical movements could only serve to increase the patriciate's

nervousness about allowing popular participation in government to get

out of hand. At the shrieval elections in September 1404:

such an exceeding number of apprentices and serving-men, belonging to

citizens of the said city, as well as of other men, strangers to the freedom

of the City, was, without any summons, assembled together in the said

Guildhall; and so loud and so clamorous was their shouting, that the Mayor

and Aldermen were unable to understand the reason for their noise; to the

manifest troubling and disturbance of the said Mayor, Aldermen, and Common

Council, there summoned.

[Riley, op.cit., 560.]

This was used as the rationale for an ordinance that only individuals

specifically summoned by the city sergeants might enter the Guildhall

to participate in elections; and such summonses would be limited to

Common Councillors and other citizens of substance. This kind of limitation

was not new, but had been the subject of resistance and non-observance. One

of London's historians has observed that complaint about clamorous discussion

is "the argument people take when they want to get rid of more democratic

processes" [Caroline Barron, Paper presented

at the seminar Governing London: Lessons from 1000 years", Museum of

London, 11 April 2000.]

The banners of the twelve Great Livery Companies,

hung about the Guildhall walls, are reminders of the commercial and trade

alliances that played an important role in the politics of

medieval London, even before incorporated as formal companies.

Photo © S. Alsford

The mayoralty, shrievalty and aldermannries were dominated by men from mercantile companies or wealthier crafts; during the fifteenth century they continued to be the leading decision-makers in London's government. However, the Common Council, whose membership increased to 150 and which met more regularly than it had in the previous century, had power to consent to or reject any proposed local tax levies, the admissions of new freemen, and the application of the city's common seal to official documents. There is evidence that, at least on some occasions, individual votes were tallied in deciding matters.

Centuries of renovation and occasional disasters

such as the Great Fire (1666) and the Blitz (1940) have removed much

of the original medieval fabric. This is the sole surviving 15th century

window.

Photo © S. Alsford