History of

medieval Lynn

History of

medieval Lynn History of

medieval Lynn

History of

medieval Lynn

| Origins and early growth |

The site of Lynn flanked a triangular bay, into which emptied the Nar and other Norfolk rivers, at the south-eastern tip of the great estuary known as the Wash; it had more direct access to the Wash than it does today, after centuries of silting and land reclamation. The light soils of the countryside to the east were (or became) suitable for raising sheep, which provided the fertilizer for growing cereals such as barley, wheat and rye. To the west, the rich, heavy soil of the Fenland supported sheep and cattle and therefore dairy products. Lynn's location represented a convergence of road, river and sea routes. The Little Ouse river ran south from Lynn and, before it turned westwards, was connected to the Great Ouse and thereby the Nene (which two served several inland counties) via artificial channels. At the same time, the site was close to several important land routes, including the major east-west route across the northern fens, which led into northern Lynn. These linkages into the rich agricultural hinterland of the Fens, western Norfolk and the east Midlands, and (in the other direction) to the ports of northern Europe, put it in a good position to become a trading centre.

The town now known as King's Lynn was, in medieval times, rather Bishop's Lynn (though the qualifier was little used). This is because it was taken under the wing of the Bishop of Norwich in the late eleventh century, one of the earliest of numerous deliberate seigneurial foundations of "new towns" that took place between that time and the mid-thirteenth century. However, although certain elements may have been planned, others have more the appearance of organic growth; Lynn does not represent a "planted town" but one developed out of an existing trading community. When Henry VIII took over the lordship of the town it was renamed King's Lynn.

The name "Lynn" has an ancient derivation, perhaps from a Celtic term meaning "pool" or from an Anglo-Saxon word for "torrent" [1], with either referring to the fact that its site was part of an estuary lake where various rivers flowed into the Wash. This lake was surrounded by earth banks and the site of Lynn sat at the narrow neck leading from the estuarine lake into the Wash; this was a likely crossing point of the estuary – an ancient ferry right was located here – and here too the channel would have been deep enough to accommodate ships. The sea bank had contributed to silting and the formation of salt marshes. So many of the local settlers were harvesting the salt through saltpans in the neighbourhood of Lynn, as scattered references in the Domesday book (where the name is rendered as Lena or Lun) reveal, that a trade surplus must have been produced. The salt was attached to sand and the separation process resulted in piles of discarded sand; this process having been going on for centuries, it was a major factor in raising the level of the land above the marsh, to the point where it became possible to build on the often quite sizable waste heaps thus created. Many of these saltern mounds are still visible today. The same process of reclamation left the site riddled with watercourses (locally called "fleets", from the Anglo-Saxon term meaning creek) ranging in size from streams to small rivers, and the course of these likewise exercised an influence on the topography of settlement, whose beginnings were partly on the reclaimed land near the mouths of the fleets.

At this time there seem to have been people living in all of the areas that later became West Lynn (on the far side of the river), North Lynn, Bishop's Lynn, and South Lynn, and the last was sufficiently populous to be considered a village. The Bishop of Thetford (later of Norwich) had a manor centred at Gaywood (where many other saltpans were located), but extending down into the future Bishop's Lynn. North of Gaywood was the estate of Wootton, held by the king in 1086. Many of the earliest settlers in these various districts must have been working the salterns, and it was likely the availability here of salt, important for the curing of meat and fish, that attracted visits from traders of north-western Europe. If so, such trade would also in time have extended to the wool and grain produced in the region, as fenland was reclaimed for agriculture, and their exchange for such products as stones and furs. Fishing was also likely an early item of trade. As this trade regularized, a few of the foreign traders may themselves have settled. These informal markets probably took place along the shoreline, and not necessarily at a single location. Bishop Herbert de Losinga's first act as regards Lynn was, following his transfer of the episcopal see to Norwich (1096), to build at the seaward end of Gaywood, upon the request of those settled in that vicinity, a parish church dedicated to St. Margaret. At some point in the first two decades of the twelfth century, he placed this church under the jurisdiction of the monastic priory of Norwich cathedral, together with a market held each Saturday and an annual fair held over three days around the feast of St. Margaret. It was not normally the Crown's practice to sanction two markets within close proximity of each other. So when, ca. 1108, Henry I granted Wootton to his butler, William d'Albini, and the grant included a half-share of the market, its tolls, and the port where ships could moor, this was perhaps part of a compromise to which the bishop had agreed, intended at eliminating any market in Wootton which might be competitive with that in Lynn, and compensating Albini with an interest in the Lynn market.

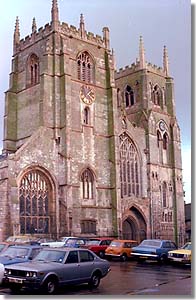

St. Margaret's Church

western end (as seen from near the gildhall)

photo © S. Alsford

Bishop Herbert's actions may have been motivated by a wish to capitalize on the growth of trade using the Wash, by trying to make Lynn a focus of that trade. The northern and southern bounds of the parish of St. Margaret's were two tidal fleets that were wide enough to be navigable and had been the sites of salting operations at some time; they were later known as Purfleet and Millfleet, respectively. They provided an added advantage to Lynn as a site attracting trade, since the fleets offered a sheltered anchorage for ships carrying visiting merchants. The western boundary was the location of the weekly market, held Saturday at the water's edge – it being described as a "sand market" (perhaps implying the site was partly underwater at high tide, a ploy to avoid having to pay market tolls to the king). The eastern boundary was the sea bank. The priory-church was built on the edge of the Saturday Market. There was already a church (All Saints) established in South Lynn, which was similarly transferred to the cathedral-priory. Early building in Lynn seems to have focused along the river-bank north of the market and perhaps even more so in the area east of the market and priory; by mid-century the population in the latter area had become heavy enough to warrant founding St. James' Chapel in that easterly quarter. A public quay – the Bishop's Staith – was built at the point where Purfleet entered the river.

By establishing what was in effect a town and helping develop its facilities, the Bishop could hope to increase his own revenues – from such sources as tolls, rents, building licences, and court fines – as a result of the stimulation of local commerce and the increased settlement which the commerce would in turn stimulate. We cannot ignore the possibility that the foundation was part of a larger policy of Bishop Herbert, of which the transfer of the episcopal see to Norwich and the attention paid to Yarmouth may have been other components. By mid-century the population had increased to the point where settlement had spread north of the Purfleet, facilitated by the presence of a bridge across the fleet; part of the population expansion was due to the introduction of a Jewish community, which was the target of attacks in 1190, perhaps mainly from foreigners in Lynn. The Bishop treated this secondary area of settlement like a separate town, confirming (ca.1146-50) to the settlers on this "new land" a market (on Tuesdays) and fair they had probably already established, and founding the chapel of St. Nicholas there to provide for the spiritual life of the residents of this northern section of Lynn. This Newland he kept under his direct jurisdiction. A second bridge was subsequently built further east.

This second "new town" was bounded by Purfleet on the south and the River Gay to the north. If planned, the layout may have envisaged a parallel series of roughly evenly-spaced north-south roads, cross-cut by Dampgate, and with the market absorbing the northwest corner adjacent to the river; but more likely the lines of roads were already dictated by existing residences. It was perhaps the anchorage in the mouth of the River Gay that had encouraged the growth of this market nearby, which in turn attracted settlement. There were lesser fleets connected to the Gay, in part by canals dug by the settlers, and here several staiths are known to have been located. A mill for grinding the townspeople's corn was built by the Bishop and served by another such channel. Before the end of the Middle Ages, the Common Staith had been established on the river-bank at the Tuesday Market, although originally the whole of the bank there was likely a landing place for ships. The Bishop's steward administered justice and collected tolls from a hall in the marketplace; court sessions were held each Monday. At the southern end of the marketplace were temporary booths where visitors and residents could buy the medieval equivalent of "fast food"; in time these booths evolved into permanent buildings. As land was reclaimed from the river, the western side of the market, facing the river, similarly came to be occupied by buildings; this was likewise the case with the Saturday marketplace.

However, just as the small market settlements pre-existing the episcopal 'foundations' in both central Lynn and the Newland mitigate against calling Lynn a planted town, it might also be going too far to suggest that Lynn was a " planned town". Although some features were doubtless the result of forethought, the topography of the site was a great influence on the evolution of the layout of the town. This was determined partly by stretches of raised ground (the product of silting and salting) west of the sea bank and to a lesser extent by the firm banks of the fleets, both of which provided natural locations for roads; and partly by the need to connect east-west land routes and the points where ships could load or unload goods. However, it was the north-south road connecting the Saturday and Tuesday markets, thanks in part to the original bridge over the Purfleet, that was the focus for settlement.

It is perhaps best to say that Lynn came into being through a combination of natural growth, stemming from trade contacts originating through the salt industry, and conscious intervention by authorities who could stimulate the growth of commerce and settlement by providing them with advantageous institutions. An indication of how fast Lynn was developing is given by the Pipe Rolls of 1165/66 and 1166/67 which include a long list of Lynn residents fined for some unspecified offence; this appears to be part of the administration of the Assize of Clarendon, one of Henry II's legal reforms to try to restore law-and-order to England after the Anarchy. The assize was concerned mainly with rooting out felons and those who harboured them, but judicial sessions may have given cognisance to other complaints of unruly behaviours. If we posit that part of the initiative to urbanize Lynn came from some of the settlers themselves, but that the bishop was reluctant to grant them the degree of burghal privileges and independence they might have wished, then possibly the 139 Lynn offenders represent an early attempt at collective resistance to episcopal domination, even an attempt to form a merchant gild -- some of those listed being ancestors of men later mayor or gild alderman at Lynn. The offenders included two merchants, three tanners, leather-workers (a parmenter and a cordwainer), a weaver, and possibly a jeweller; among immigrants from local villages, others were from Huntingdon, Lincoln, Stamford, and London, as well as at least one man of foreign origins. This evidence suggests how Lynn's economy was diversifying and how the port town was attracting settlers from far afield.

| 1 | I am grateful to Dr. Anthony Durham for the latter new interpretation. |

main menu |

next |

| Created: August 29, 1998. Last update: September 1, 2020 | © Stephen Alsford, 1998-2020 |