The prospects of old age | The medieval poor house | Retirement homes | Further reading

| RETIREMENT | ||

|

INTRODUCTORY ESSAY

The prospects of old age | The medieval poor house | Retirement homes | Further reading |

||

There was no systematized or institutionalized retirement in medieval lay society. Yet there was recognition that, for those who lived long enough and had or could find the means to provide themselves with the basic resources (food, clothing, shelter) for survival, retirement was a possibility. Old age, when coupled with infirmity or disability (e.g. blindness), was seen as a valid excuse for ridding oneself of responsibilities. There are numerous cases of townsmen withdrawing from positions in local or royal service on such grounds, even though some may have been excuses behind which lie other reasons. On the other hand there was no social expectation that men would retire at a certain age; London seems an exception in ruling, in the fifteenth century, that no-one over 70 need undertake jury service if he did not wish. But 70 was very old; the harsher living conditions of the Middle Ages brought many to the condition of physical decline, that we associate with old age, in their 50s. Probably only about 15% of the adult population lived to a modern retirement age.

Retirement was necessarily a personal decision and it was largely up to individuals to take the initiative in providing for their retirement years. It is assumed that many retirees would have been supported by their families, through informal (i.e. unrecorded) arrangements, or supported themselves from wealth accumulated during their working lives. We sometimes find provisions in wills for the support of widows, while dower rights were partly intended for that purpose, although also to ensure the maintenance of underage children. Those townsmen who could not call on familial support and lacked the means to support themselves, except through earning a living, worked until they dropped. At the other end of the socio-economic scale, some of those wealthy townsmen who had invested in country estates (as quite a few did) may have retired there in their final years.

For townspeople there were no company pensions, for there were few "companies" – most of those involved in commerce or industry being self-employed, at least in the later stages of their careers. The Church was the closest to a perpetual corporation that looked after its own. In the case of government, we do find cases of bureaucrats upon retirement being rewarded for long or faithful service with annual allowances (e.g. a Coventry minstrel), and fewer of negotiating a pension in advance of accepting an appointment, this was neither regulated nor systematized. Such cases are rarer in local government, where the majority of participants were elected for brief periods rather than being career administrators, and more common at the national level, perhaps helping explain why positions in royal government were sought after.

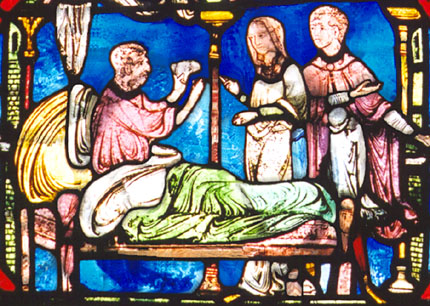

The family was necessarily the first line

of support for those in their years of decline.

From a window in the quire of Canterbury Cathedral.

Photo: © S. Alsford

A few of the aged who became too ill or infirm to work received support from a charitable institution, such as hospital or gild (in the case of members in decline). Socio-religious gilds were much more active here than craft gilds, since charity was one of the purposes of their foundation. The majority made provisions for support of members who were in decline, occasionally even non-members. Hospitals had a variety of purposes and some were specialized, but their most prominent role was to look after the poor, old, and sick who lacked the means to take care of themselves. Some examples at York and Norwich are shown below, and Canterbury has two good examples in the Eastbridge Hospital and the Poor Priests Hospital. Since the elderly were particularly prone to both infirmity and poverty, it seems likely that many hospital residents were older members of society, although only a handful of hospitals explicitly focused their efforts on the aged, such as one founded at Nottingham in 1392 intended for impoverished, aging widows. The aged who lacked family support were particularly susceptible to falling into poverty.

The late thirteenth century saw a second wave of hospital foundation; this was a time when town governments were expanding their spheres of activity and when increasing socio-economic differentiation within urban communities may have stimulated a sense of responsibility among the urban elite to provide for those less fortunate, and their own souls at the same time. Many of these and later hospitals were founded by leading townsmen, individually or in groups (sometimes socio-religious gilds), and typically imposed a semi-religious rule upon the inmates while also supporting one or more secular clergy who, sometimes together with the inmates, had the duty of praying for the souls of the hospital benefactors. The Hospital of St. Mary at Yarmouth is one example; it provided a refuge for impoverished adults of at least 30 years of age who had no family to support them, and it may well be that aged persons represented a large proportion of the inmates. Other hospitals were founded by men of religion, e.g. St. Mary's at Chichester and St. Bartholomew's in London.

A trend in the fifteenth century was to endow the almshouse type of hospital, to accommodate the poor or aged. The London foundation of Richard Whittington is one of the best-known examples. As did the urban hospitals founded in earlier periods, these attracted donations from citizens, often in the form of small bequests. A few of these foundations specified a minimum age of inmates, indicating their focus on the elderly. In the same period some hospitals originally established to offer charitable shelter for the infirm or aged poor became almshouses for those wealthy enough to pay for permanent accommodation and support. For example, St. Bartholomew's hospital at Sandwich, founded (or refounded) ca. 1217, was already by the end of that century including among its residents those of whom entry fees of up to £10 were demanded in return for personal sleeping spaces partitioned off on either side of the large chapel. By the late fifteenth century it had become more exclusive, catering to local well-to-do retirees; the communal hall had been converted to apartments and other almshouses had been built around the chapel, each residence comprising at least a living room and bedroom, and some having one or more additional rooms for food storage/preparation.

Despite the Church teaching the importance of charity for the good of the giver's soul, and despite some provision by the wealthy during life and particularly at death for charitable donations, including to hospitals, only a small percentage of the aged poor could have benefited from that resource. As noted above, residents were not necessarily penniless, for some were accepted only on payment of a sizeable entry fee or an annual amount for bed-and-board. In some cases preferential treatment was given to freemen or householders in the locality, to the detriment of the unenfranchised poor. So, to some extent, hospital foundation represents the urban upper class providing for its own. There was no real effort to address poverty on the broader scale, as a social undesirable, for poverty was part of Christian tradition, and was largely accepted as within the natural order of things; only as the economy worsened towards the close of the Middle Ages was there a growing resentment of those paupers (such as beggars and vagrants) on the peripheries of society.

|

|

|

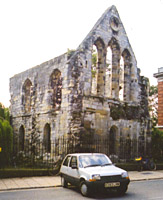

At hospitals such as St. Leonard's,

York, of which only ruins remain (top

left), and St. Giles, Norwich,

(below) which remains

largely intact and impressive, elderly inmates could be assured

the necessities of life in their final years; hospitals and other

religious houses also assisted poor non-residents with daily gifts of

food and drink (top

right). The missions of St. Giles' and St. Leonard's

continue today with modern institutions. (click on the images for enlarged versions and/or more information) |

|

|

|

For those of means, however, there were several other options open for arranging for support in the latter part of one's life.

It was not a common occurrence for medieval merchants or craftsmen to put aside their occupation and become monks or friars in mid-life, although their sons or daughters might be attracted by the religious life, and large families often had at least one member who had chosen to pursue a career in the church. However, the standard of living in religious houses generally being in some respects higher than that of secular society, some of the wealthier townspeople negotiated arrangements whereby they would spend their declining years in relative peace and comfort in a "retirement home" environment of a friary or some other religious institution, including hospitals – the result of which was that paying guests consumed resources originally intended for the poor. Such maintenance contracts, specifying the terms of the accommodations, meal provision and other aspects of the retirement – the medieval equivalent of a modern pension – are known as a corrodies.

The patrons of monasteries, particularly the king, arranged for corrodies to reward their old servants, again consuming the resources of such institutions; this came to be perceived as an abuse. The sale of corrodies to lay persons could prove profitable, assuming purchasers did not live long enough that maintenance costs exceeded the value of the purchase price; endowment of property providing annual revenue, rather than a straight cash transaction, might be more lucrative in the long run, but provision of corrodies for money or real estate was a gamble for both parties. Being contrary to the main purpose of religious institutions, diverting their accommodation resources from novices, and bringing into the religious communities potentially disruptive elements (such as women) it came under criticism, but remained attractive for many religious houses – perhaps particularly those in financial difficulties – and for purchasers, who appear prepared to pay sometimes inflated prices in return for the physical and spiritual benefits of residing within a religious community. Many who did not retire to friaries chose to be buried there – an indication of the high regard in which these institutions were usually held.

Sometimes a corrody might involve provision of the necessaries of life, but not accommodation; for example, ca.1176 John Calderun, perhaps sensing himself failing, granted several plots of land in Canterbury to the cathedral priory there, in return for a promise that his wife Matilda would be provided by the priory with a daily food allowance, (comprising three loaves of different kinds, 3 gallons of ale, and one or two main course dishes such as would be served to the monks), and an annual clothing allowance (one mantle, and one pair of boots), the priory being careful to specify that these assets could not be claimed by Matilda's heirs. It may be that she continued to live with John's son, who was a party to the agreement. On the other hand, support might be primarily in the form of accommodation. For example, in 1276 the cathedral priory assigned Sibyl, a widow, a house in Canterbury, together with an assurance of keeping it in repair and of delivering there, at no cost to her, a cartload of wood each year; she was also to receive an annual payment of 40s., which would enable her to buy her necessaries. In return Sibyl surrendered to the priory her claim to free bench in her late husband's properties in the village of Elverton.

Maintenance agreements could be made with younger members of the family, neighbours, or friends, or respectable members of the community, or religious houses (e.g. hospitals). In many cases, the business-like character of these agreements likely disguises an element of trust or goodwill, or sometimes a landlord-tenant bond, which lay behind the relationship of the parties to the agreement; on the other hand, the formality of the agreements may reflect concern on the part of the elderly that they risked being treated poorly if reduced to dependency on others. In some cases, however, the retiree and the maintainer had no evident relationship, and the arrangement seems purely a matter of business. This may have been a necessity for the elderly who had no children or other close relatives on whom they might rely. It is believed that in the decades after the Black Death had taken its toll in the mid-fourteenth century, this situation may have become more common, because of high mortality among the young and the division of families as a reduced workforce encouraged migration to where better career opportunities lay.

These agreements were essentially contracts in which the retirees turned over their real estate, or in the case of widows their dower rights, and perhaps (sometimes explicitly) most of the moveables therein, to the maintainer conditional upon the latter providing accommodation, food, clothing and other necessaries on a regular basis for the remaider of the life of the retirees or, less commonly, for a specified period. For example, a contract at Coventry in 1332 involved Henry le Spicer and his wife Mary agreeing to give Henry's father, Richard:

Such agreements can be considered a sort of pension, and the pensioners might often stay on in the homes they had turned over to the maintainer, or go to live in the maintainer's home, or be supplied with a new residence. The more property retirees had to bargain with, the better the conditions they might hope to negotiate. In the case of widows or other propertied women who found themselves in financial difficulty in the later years of life, the arrangement might take the form of management of the property until the woman's finances were on a sounder footing. For the party taking on maintenance obligations, the advantage was access to a source of revenue; this was useful to younger generations of the family, to religious institutions that relied on donations, and to the entrepreneur.

For once, we tend to have better information about maintenance agreements in rural rather than urban communities, since villagers' property was held of manorial lords and any transfers had to be reported in the manorial court. Otherwise much of our knowledge of urban agreements comes from the records of religious institutions, or from court cases involving contractual disputes.

Maintenance agreements did not always work out as planned, sometimes because the maintainer reneged on the agreement, or sometimes because the retiree became dissatisfied with the constricted terms interfering with lifestyle. In poorer households an aged parent might expect no more than a bed in the corner and a share in family meals. Wealthier townspeople, however, had in mind private quarters, access to cooking and storage facilities, an adequate diet, regular allowances of new clothing, provisions for a servant, and freedom to entertain or be entertained elsewhere. For those who could afford it, retirement – if coupled with fair health – might be quite comfortable. However, it seems likely that retirement was most commonly prompted by failing health.

A York

gildhall incorporated hospital facilities.

(click on the image for more information)

There is as yet relatively little written on retirement provisions or strategies in a medieval urban context.

CLARK, Elaine. "Some aspects of social security in medieval England," Journal of Family History, vol.7 (1982), 307-20.

CULLUM, P. H. "Cremetts and Corrodies: Care of the Poor and Sick at St. Leonard's Hospital, York, in the Middle Ages," Borthwick Papers, no.79 (1991).

MCREE, Ben R. "Charity and gild solidarity in late medieval England," Journal of British Studies, vol.32 (1993), 195-225.

RAWCLIFFE, Carole. "The hospitals of later medieval London," Medical History, vol.28 (1984), 1-21.

ROSENTHAL, Joel T. "Retirement and the life cycle in fifteenth-century England," pp.173-88 in Aging and the Aged in Medieval Europe, ed. M. Sheehan. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1990.

STEUER, Susan M.B. "Family Strategies in Medieval London: Financial Planning

and the Urban Widow, 1123-1473," Essays in Medieval Studies,

vol.12 (1995).

http://www.illinoismedieval.org/ems/VOL12/steuer.html

|

|

main menu |

|

|

||