Seal matrices and impressions from thirteenth and fourteenth

centuries, displayed in the Museum of London. They include those of a Southwark blacksmith,

members of the Picot family of merchants, as well as women who were conducting

business in their own right.

Photo © S. Alsford

The growing use of written documents to record property transfers was paralleled by the use of seals to authenticate them, and this came also to apply to documentation of other legal and financial transactions. High-ranking individuals and royal officers might have seals in the Late Anglo-Saxon period, and their use spread down the socal scale to minor officials; the development of heraldry seems to have given impetus to use of seals among the nobility. By the thirteenth century they were becoming common among townspeople who were wealthy enough to own property or be active in large-scale commerce.

In essence appending one's seal showed that the sealing party was present at, and (in the case of the principals) consenting to, the transaction – although in time this devolved into a ceremonial convention; they were also used to imprint on goods and property a mark that identified the owner. A personal seal matrix generally took the form either of a finger ring (signet) or of a portable stamp with small handle containing an aperture so that it could be carried on a chain; rings became more popular in the fifteenth century, as private correspondence was on the increase.

A fifteenth century copper alloy finger-ring with a merchant's mark

on the bezel, found in Colchester and now in the Castle Museum there.

Photo © S. Alsford

Seals bore some icon representing the owner; this might be the owner's initials or monogram, some distinctive emblem such as an armigerous device (if the owner had the right to such), an animal design, or (for instance) a ship; one seal in the Museum of London collection, for example, bears the image of a squatting squirrel with an inscription meaning "I crack nuts", likely a play on the surname of the owner. In some cases a legend around the perimeter enclosed the central image.

Use of common icons may have been found increasingly prone to confusion as the number of merchants and others using seals proliferated; either for more assured authentication, or to differentiate themselves from seal iconography of the nobility, townspeople turned more to the use of what are known as merchants' marks. Although distinctive markings to represent individuals have a long history, and were used in many European countries, in England medieval tradesmen's use of a distinctive sign system began to appear from about the mid-thirteenth century and became widely used during the fourteenth.

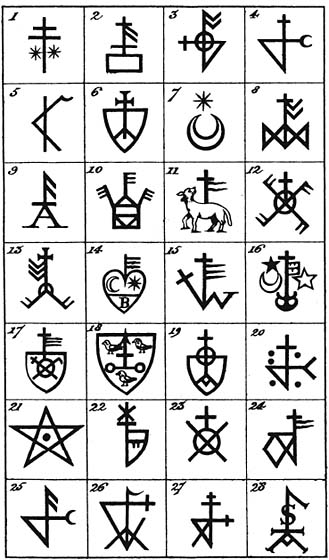

A selection of merchants' marks

from hundreds copied and compiled by William Ewing, "Notices of the Norwich Merchant Marks,"

Norfolk Archaeology, vol.3 (1852), plate 1 (with substitutions)

The merchant's marks above were sourced mostly from seals attached to original deeds.

All examples shown here, except for nos. 26-28, date between 1276 and 1393. They include

the marks of:

What have been categorized, slightly misleadingly, as merchants' marks, (for they were also used by artisans and others), while not an idea originating in the medieval period, became increasingly commonly used during the Late Middle Ages. They were at first simple geometric symbols combined to create a unique pattern for each owner, sometimes incorporating one or more initials of the owner's name, often monogram-style, or even some simplified iconic representation of an object connected with the owner's occupation. Over time these marks tended to become more complicated; some seem to mimic coats of arms. It is not evident that any rules existed to guide the formulation of a mark, but nor was their design solely a matter of personal caprice; there seem to have been some generally understood principles that merchants could use to create their own marks, with a view to ensuring they would be unlikely to duplicate marks of at least fellow-merchants of the same town.

The fundamental purpose of merchants' marks, as with seals, was, in an age when the ability to write was not widespread, to identify the owner as a signature would today (or, in the digital world, a password), but more in the style of a modern livestock brand – and indeed the marks may have been used for just such a purpose. They were usually applied through a seal, or carved into or painted onto objects.

Bakers were supposed to apply to the loaves they produced, and vintners the barrels they owned, their marks, so that any non-standard items could be used to identify the owner; such maker's marks (precursor of trademarks) are also found, usually in a slightly cruder form, on building stones to identify masons involved, on some pieces of pottery inscribed into the clay before firing, and on various other manufactured items. Like trademarks, they were an assurance of quality of workmanship. For merchants, however, the marks became just as much indicators of wealth and status, the mercantile equivalent (if less prestigious) of an aristocratic heraldic device, passed down in families, with slight modifications made by each succeeding generation; this did not preclude different members of families adopting totally different marks. Mercantile families that obtained grants of arms might impale the arms and the mark on the heraldic shield.

That one of the late fifteenth-century floor tiles found at

an important leper hospital in Leicestershire bears a merchant's mark may indicate

the merchant was a donor to the hospital. British Museum.

Photo © S. Alsford

Merchants' marks were used at first mainly for business purposes (defined broadly),

appearing on documents from Bristol and Norwich in the latter half of the thirteenth century;

but later to identify ownership of personal items or to associate the owner as a benefactor

(whether in life or through bequests) responsible for funding improvements to church fabric.

Their uses included marking:

(above left) Spandrel of the door-frame of Mistley church, Essex, with the mark of

Richard Darnell, who bequeathed money to rebuild the south porch, carved into it.

The same mark had earlier been used (1446) by a leading Ipswich merchant, William Baldry.

(above right) This baluster jug of ca.1400 is decorated with a mark, though whether of

the potter who made it or the customer for whom it was made, is unknown.

Colchester Castle Museum.

(below) One end of this timber beam across a wagon entrance bears the merchant's mark

of Augustine Steward (1491-1571), who built a house here on Elm Hill, Norwich, as

his residence during his later life; the previous residence on the site, owned by

the Paston family, had been destroyed by fire in 1507. Steward, a mercer, was

the city's mayor in 1534, 1546, and 1556; the other end of the beam (not visible

in photo) bears the arms of the Mercers' Company. Steward's previous residence,

not far away, looking across Tombland towards the cathedral, had also borne his mark,

embossed on a corner stone. Steward's widowed mother, after remarrying, traded under

her own name and had her own merchant's mark.

Photos © S. Alsford

Merchants' marks were also placed, and can often still be seen, as a form of commemoration, within churches and monasteries to which the owners made significant donations or bequests; a reference to this is made in Piers Plowman. One example is St. Margaret's, Ipswich, where the late fifteenth-century clerestory has associated with it multiple instances of the merchants' marks, initials, and monograms of the Hall family: dyer John, bailiff 1489 and 1495, possibly the son of mercer Robert Hall prominent in borough government in the reign of Edward IV; John's wife Katherine; and their son William, a clothier and dyer and several times bailiff in the early sixteenth century. The marks are sculpted onto shields or into architectural elements. John's donations to the church were significant enough that he felt emboldened to request in his will that he be buried in the church nave in front of the crucifix. His merchant mark is made up of simple iconic representations of dyers tools for agitating cloth in, and removing it from, the vat. [John Blatchly and Peter Northeast, "Discoveries in the clerestory and roof structure of St Margaret's church, Ipswich", Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology, vol.38 (1996), p.396.]

Stone-carved merchant's mark of John Hall

Extracted from a photo by Birkin Haward

Merchants' marks might also be inscribed on tomb monuments. For sintance, the merchant's mark of Thomas Pounder (d.1525) was included on his memorial brass, produced at his, or his widow Emma's, commission for installation in St. Mary Quay church, Ipswich. The mark appears on a shield positioned between the heads of Thomas and his wife, substituting for an armigerous device to which Pounder had no claim; below their figures two sons and six daughters are depicted. Produced in Flanders, it cannot be relied on as an accurate depiction of the individuals, but since it was evidently custom-produced to specifications, it may be a reasonable approximation. Thomas is shown clean-shaven and bareheaded, with neck-length hair, wearing a fur-lined gown with fur collar; Emma (who continued to run Thomas' export/import business for many years after his death) wears a pedimental headdress with veil at the back and a gown over a kirtle with embroidered neck-band. The brass also bears the arms of Ipswich (incorrectly represented), of which Thomas had served as one of the borough coroners for almost all of the period 1515-1523 (a colleague of William Hall in local government) before being elected bailiff in the latter year, and the arms of the Merchant Adventurers' Company, of which he was a member. Thomas' bequests included a small ship, perhaps that in which he sailed to Iceland in 1506 to trade for fish and blubber; a decade later he is seen exporting cloth to the Low Countries.

Photo © S. Alsford

(above) The Pounder brass.

(below) Merchant's mark on the brass of Thomas Pounder, as drawn by W. Hagreen

for the frontispiece of Wodderspoon's Memorials of Ipswich.