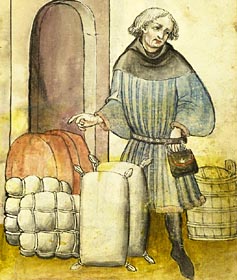

This portrait represents Peter Neumeister of Nuremberg,

described as a "kaufmann" (meaning a shopkeeper), although the large containers

of goods surrounding him outside the doorway of his shop(?) suggest he was

more than a small-scale trader. His right hand indicates his ownership of

the merchandize, while his left reaches into the purse at his waist,

symbol of mercantile status. He wears a fur-trimmed gown with a hood, indicative

of his one-time prosperity. The portrait was created after his death in 1440,

by the authorities of the retirement home in which he expired.

From the Hausbuch der Mendelschen Zwölfbrüderstiftung

In most of medieval Europe, merchants, and still less pedlars, were rarely considered a suitable subject for portrayal, either through the arts or literature, until the Late Middle Ages; this owes a good deal to the fact that the main consumers of cultural products belonged to social groups (nobility and churchmen) who found merchants somewhat distasteful. The rediscovery of ancient philosophers aside, merchants first appear – textually or visually – in conjunction with Biblical stories, sermons, and moralistic tales; and then, consequent to their roles as leading sponsors of improvements to churches and founders of charitable institutions, in ecclesiastical memorials.

The fifteenth century saw some cultural products being targeted at the merchant class, which doubtless wished to see itself reflected in portrayals of society, and which had developed not only a self-satisfaction but pride in its role in, and contributions to, what it understood as the common good, a concept itself undergoing transformation; many of the creators of such products were themselves townsmen, or at least closely associated with urban society. Through brasses, tomb effigies, and donor panels in stained-glass windows, we start to see more depictions of specific individual merchants, untrustworthy though they may be as documentary portraits. The introduction of the printed book encouraged the illustration of works formerly distributed only in textual form, although for those who could still afford the more prestigious hand-produced copies of works, illustrations were, perhaps more than ever, a strong selling point. Most artistic representations of merchants in such works originate from outside England, but still give us some sense of common traits of traders and their commercial/industrial contexts across Europe.

(above)Two merchants, depicted with the characteristic trappings

of fur-lined clothing and purses at the waist. From the Schachzabelbuch, a German

verse translation, produced 1337 by of Konrad von Ammenhausen, of

Cessole's De Ludo Scachorum.

Some fifteenth century versions included illustrations; this one (1467), accompanied

a moral tale to show how friendship

is a greater treasure than material wealth.

(below) Merchants making a deal at a port; from a late fourteenth century translation

by Jean Golein of extracts from Giles of Rome's

De Regimine Principum

.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des Manuscrits

Any number of the better-documented medieval townsmen could be used to illustrate characteristics of merchants, their careers, and their accomplishments, and brief accounts of a number can be found elsewhere on this site. Here we will look at one long-celebrated, Sir John Crosby of London, another slightly less well-known who operated as a middleman, Simon Eyre of London, and a third who has only come to public attention in recent years, Robert Toppes of Norwich. Each is interesting in part because of the material traces that ramain of his existence, in the form of architectural legacy and memorial portrayal.

A series of small watercolours, on paper, of London aldermen and sheriffs was undertaken ca.1450 by Roger Leigh. Although the artist may well have seen many of his subjects, who were his contemporaries, the portraits are rather stylized , using a limited set of models all in much the same pose, adapted through variation in colours and details to differentiate the numerous persons represented. Each figure balances on his right hand his own heraldic crest and rests his left arm on a board topped by the city coat of arms and bearing the arms of twelve previous aldermen for the same ward, whose names are written underneath. The purpose of these portraits was not to create lifelike images of the individuals who were the subjects, so much as to highlight the dignity of civic office-holders and commemorate the public services they had performed while in office. [Robert Tittler, Portraits, Painters, and Publics in Provincial England 1540-1640, Oxford University Press, 2012, p.115] The illustration in Ricart's Kalendar of a mayor being sworn into office is, to some extent, in a similar mould.

One of the most frequently reproduced portraits of

the Leigh series is that of Simon Eyre

Photo S. Alsford, from an exhibit in Dragon Hall, Norwich.

The original is in the London Metropolitan Archives.

Suffolk-born, Simon Eyre moved to London when apprenticed there to a dealer in second-hand clothes. In 1419 he improved his status by transferring to the Drapers' Company. He made money not as an exporter/importer but as a middleman, buying cloth manufactured in rural areas, then selling it to the king's Wardrobe and to other merchants, notably Italians, from whom he purchased dyes and spices for redistribution to other parts of England. His success in this role led to him being chosen warden of the Drapers' Company in 1425 and again in 1435.

Meanwhile Eyre had been elected one of the city's sheriffs in 1434, despite trying to excuse himself from the burdensome office by claiming not to be wealthy enough. He was made a common councillor, and then alderman (Walbrook Ward) in 1444, by which time he was already active on a project to rebuild as a public facility the Leadenhall granary, whose site had been acquired by Whittington for the city; the famines of the late 1430s had perhaps re-emphasized the need for a public store of grain. Excavation of what little remains of this structure indicates it was solidly built to hold stockpiles of grain, kept on upper levels of the building (while the ground floor had no windows) to make things harder for human or rodent pilferers, that it had defensive features in case of grain riots, and stairs at either end by which grain could be brought down for distribution to the citizenry, at affordable prices, in times of shortage. This civic-minded initiative may have been what got Eyre elected as mayor in 1445, although his Leadenhall complex would later be put to uses other than he had intended.

Part of the interior of Leadenhall, in its Victorian

iteration, still today one of London's most famous provision markets.

Photo © S. Alsford

Simon Eyre continued to serve as alderman, for different wards, up to his death in 1458, and avoided involvement in other city committees in order to continue focusing on the development of Leadenhall, adding a free school to teach children to write, understand Latin grammar, and sing. His heir was a single son whom he had constantly had to bail out of money troubles. This may have been an added factor in his bequest of the huge some of some two thousand pounds – about a third of his total worth – for his executors to establish schools, maintain buildings, and pay salaries; however, his executors were less visionary than he and spent the money to maintain the church where he was buried.

The next generation of leading Londoners included John Crosby, a man somewhat in the Whittington mould, financially successful and providing services that put him on good terms with the king. Interestingly, both men became, after their deaths, the subject of rags-to-riches fabrications: whereas the orphan Whittington took his first step towards fortune when found sleeping on the steps of his future patron's home, in Crosby's case his surname provided grist for a tale that he had been a foundling, discovered by a cross. We should not dismiss such tales as worthless, however, for they express much the same notion of London as the font of prosperity that is echoed in the city statue to Commerce, whose hand displays the money that new-comers who take up citizenship can expect to make.

Crosby was in fact the grandson of a like-named man who had served as one of the city aldermen and who had owned, and handed down to Crosby's father, a manor just west of London. The grandson was apprenticed to a London grocer with Yorkist sympathies, and took up citizenship as a member of the Grocers' Company in 1454, serving as its warden 1463-64, although he seems mostly to have exported wool and imported luxury fabrics. By 1462 he was a merchant of the Calais Staple, later serving as its mayor. Two years later he was serving as an auditor of city accounts and was chosen as one of its parliamentary representatives; in 1468 he became an alderman and in 1470 was elected sheriff, despite being a Yorkist during the Lancastrian resurgence. In that role he helped lead the defence of the city against a Lancastrian assault of 1471 and, after welcoming a triumphant Edward IV back to the city a week later, was knighted; the arms he selected incorporated three warlike rams, perhaps a tip of the hat to the source of his wealth; on his seal, however, he used a merchant's mark. The royal confidence he had won led to diplomatic missions to Burgundy and Flanders on Edward's behalf in the years that followed, in part to negotiate commercial treaties.

It was around the time of the death of his first wife (1466), who had borne him several children (although none are known for certain to have survived him), he acquired, from the prioress of St. Helen's Bishopgate, a 99-year lease on a plot of land between the priory close and a house he already held of the priory. He used the new lease to partially rebuild and extend his house, converting it into an impressive mansion with outer and inner courtyards; it was fit to receive royalty, and after Crosby's death it served for a while as the town residence of Richard, Duke of Gloucester. The mansion was dismantled in 1910 but rebuilt in Chelsea and is the only medieval merchant's house to have survived in London.

Sir John Crosby cannot have enjoyed his magnificent new residence for many years. He drew up his will in 1471 and died four years later, leaving, besides real estate and other property, monetary bequests totalling about £3,200 [Christian Steer, "The Tomb, the Palace and a Touch of Shakespeare: The Memory of Sir John Crosby," The Ricardian, vol.16 (2006), 1], the greater part of which went to his second wife as dower. He was buried in the church of St. Helen's (where his first wife had earlier been entombed), to which he bequeathed 400 marks for a 40-year chantry, 500 marks towards the church fabric (a sum believed expended on a series of arches separating the two naves), and £40 to help the priory pay off its debts. He also bequeathed £100 towards repairs of the city gate of Bishopsgate, the same amount towards a civic project for rebuilding a tower at the Southwark end of London Bridge, on condition that project go ahead within ten years, and amounts to buy victuals for prisoners in the various London gaols. Recipients of more modest bequests included his factor, four apprentices (one of them a kinsman), a cook, five man-servants in London, a woman-servant, a scullery lad, a Florentine merchant of the Frescobaldi who was perhaps a key business associate abroad or a representative of the banking family in its London office, and a scrivener (perhaps once his clerk?).

The tomb of Sir John Crosby and his wife.

Photo © S. Alsford

Crosby's tomb in St. Helen's church is another fortuitous survivor of the centuries. It bears the effigies of Sir John and his first wife Agnes, in the conventional recumbent, praying posture. Crosby is represented as fully armed, his armour worn over what is likely an alderman's gown, though little is visible; around his neck is a collar of suns and roses, the badge of the House of York which he served faithfully. His feet rest on what is generally considered to be a griffin, though its face more resembles a sheep. Coats of arms arrayed around the base of the tomb were those of Crosby, the Staple of Calais, and the London Grocers' Company. Such an imposing memorial does not seem to have been his own idea – at least at the time he drew up his will, in which he envisaged a marble slab carved with images of himself, his wife, and their children, and a brief inscription, much like a brass. At that time he made the not uncommon provision for the possibility he might die abroad, in which case his foreign tomb as well as that in St. Helen's of his late wife were to have separate covers with their images and inscription. His executors also saw to it that Crosby's coat of arms decorated parts of the chancel to which he had made a further bequest for enhancements. Such memorializations supported testamentary desires for Christians to remember the testator and pray for his soul.

Norwich's Robert Toppes may have required a similar, or slightly more modest, cadre of domestic servants and business employees to that of John Crosby, for he operated two establishments and appears to have had a similar ambition to excel within his socio-economic group. Yet at the same time, while every life-path is individual, the central aspects of Robert Toppes' life seem quite typical of the better-evidenced instances of that urban class. In fact, he might well have remained known simply as one of those Norwich merchants who held the mayoralty were it not for the discovery a few decades ago of his association with a mercantile property which became the focus for restoration and heritage interpretation, and Toppes consequently the subject of archival research.

Although it can be estimated that he was born in the opening years of the fifteenth century, Robert Toppes' family background is obscure; the surname is found elsewhere in Norfolk but not in Norwich (although a Michael Toppay was a citizen in the 1370s), and it seems doubtful the name would be a contraction of a place-name, such as Toppesfield (Essex) or Topsham (Devon). It is likely he was an immigrant to the city with either a little money in his background or ambition combined with ability, for in 1421 he could afford the 26s.4d. fee for admission to the franchise as a mercer. This was a period when the cloth industry and trade was becoming increasingly dominant in Norwich's economy and was attracting many migrants looking to improve their fortunes. He was perhaps involved not only in the sale of cloth but also in its manufacture, for on one occasion he was referred to as a worsted weaver, although his personal role may only have been to commission piece-work.

That Toppes' cloth business prospered is shown by his rise through the ranks of the mercantile elite. He had garnered enough attention from that elite to be chosen in 1427 as one of the pair of city treasurers who held that office each year – a position of responsibility that was something of a testing-ground to weed out future civic leaders. That year happened also to be the first mayoral term of Thomas Wetherby, who would soon become the central figure in political factionalism that would embroil the city. Toppes is known to have been a member of the socio-religious gild of St. George, which was also involved in the political in-fighting. He aligned himself with the opponents to the Wetherby faction, and at one point was one of those exiled for a year for their involvement in civic disturbances. Toppes had already moved up the political ladder to a term as city sheriff (1429/30) before the trouble broke out; this was eight years quicker than the draper who had been his colleague as treasurer, although a similar promotion to the treasurers of the previous year occurred with the same interval. None of those three, however, ever rose to the mayoralty, which Toppes did in 1435, and again in 1440, 1452, and 1458; during that period he was a member of the upper council of aldermen, the top echelon of city governors. It was during his mayoralty of 1452./53 that the city Guildhall windows looking onto the mayor's court were glazed, and Toppes' coat-of-arms was placed in one of the stained-glass panels. He was also, between 1436 and 1461, chosen to represent Norwich at three (possibly four) parliaments – on the first occasion his partner was Wetherby.

Photo © S. Alsford

A portrayal of Robert Toppes and his two wives, overlooked by an angel, in

a stained glass window of one of the chapels in the market church of St. Peter Mancroft,

Norwich's civic church. It occurs as

a donor panel in a window depicting scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary, with

sainted kings and prelates portrayed in the tracery. This window, a gift to the church

at a period when it was being rebuilt through the donations of its wealthy parishioners,

also displayed Toppes' merchant's mark, the heraldic arms

he had recently assumed, and those of his second wife. David King [The medieval stained glass

of St Peter Mancroft, Norwich. Oxford University Press, 2006, lxxviii, clxxxvii] argues

that the window was in place for the re-consecration of the church in 1455 and perhaps

as early as 1453, and that there was a political dimension to its unveiling and contents.

It is possible the donation followed Toppes' third mayoral term, and was during his term

as alderman of St. George's gild,

as required by a recent settlement between

political factions.

Toppes was not only one of the leading townsmen politically, however, but also economically. He is seen participating in consortium freightings of ships carrying from Yarmouth cargoes of native cloth and wool, and returning with continental textiles, other luxury goods (wine, spices) as well as German pottery and metalwares. Like any good merchant he did not put all his eggs in one basket; in 1455/56 he is evidenced dealing in barley, salt, and herring, and he carried on his trade not only through Yarmouth but probably also through London, for he was referred to as one of its citizens and he bequeathed money towards maintenance of the road between Norwich and London. He stood among the wealthiest residents of Norwich; his executors, some years after his death (1467/68) compiled from Toppes' business account book (which has not survived) a list of over two hundred debtors, across the social scale, most in Norwich but others in fifty-one locations around Norfolk, and several in Suffolk.

He was also one of only half a dozen Norwich testators who felt able to make a monetary bequest to every one of Norwich's many churches, as well as to seventeen other churches in East Anglia (mostly associated with parishes where worsteds were manufactured). By far the largest of these bequests was to St. Peter Mancroft, which was probably his parish church and where he requested to be buried. His earlier donation of the stained-glass window was a shrewd business decision, for it was something conspicuous that would leave a memory of him, reinforced by the inclusion of donor identifiers; it might be considered a kind of advertising, although this is to interpret it from a purely modern perspective that ignores genuine religious concerns of medieval townspeople.

As a leading merchant and a man of enterprise, Robert Toppes desired facilities for transporting, storing, and displaying his merchandize. This was met through purchase of a large property – in the fourteenth century two sites, one with a stone building and the other a timber-framed merchant's house – in the southern part of the city, facing the major through-route of Conesford Street and backing onto a stretch of the river where many merchants had their own jetties and public wharves had been installed.

He proceeded, around 1427 (another indication, that early, of either his prosperity or his vision), to redevelop the existing buildings into an integrated complex to serve his business needs. The main feature was an impressively large trading hall on the jettied first floor, outfitted with expensive roof support structure and glazed oriel windows overlooking the street; Toppes seems to have had an association with local glazier John Wighton, who was made an alderman during one of Toppes' mayoral terms. In this huge space Toppes could display the range of cloths he had for sale, and at one end of the hall was a more private space that Toppes likely used to entertain clients and/or negotiate deals. No other such private showroom has survived from the Middle Ages.

The great trading hall of Robert Toppes was over 26 metres long; there would presumably have been a number of tables spread around the hall for displaying bolts of cloth. The architecture consumed huge numbers of oak timbers, and the roof support structure was decorated with fourteen delicate carvings of dragons, a traditional symbol of the city. The building is consequently now known as Dragon Hall, although in Toppes' own time it had the name Splytts.

(above) The interior of the Dragon Hall showroom today (used for interpretive purposes)

with crown-post roof and eponymous dragon carving in spandrel at top right – the

only surviving complete example. It can be seen how Toppes' new windows provided light

that would bring out the colours of the textiles for sale.

(below) Part of a cutaway model of the hall, in which Toppes is portrayed showing

his goods to customers.

Photos © S. Alsford

Toppes had storerooms for his goods at ground level and in the existing vaulted stone cellar, which Toppes extended and provided with an access from the rear yard, where there was further warehousing; the cellar was presumably used for goods other than cloth, which did not fare well in damp environments. He likewise invested in sculpted stone corbels at either end of the street-facing corners which may have carried a subtle marketing message, and in a carved stone doorway surround that would help impress arriving clients with the quality and solidity of his business. Immediately within the entrance was a smaller hall where potential clients may have been offered food and wine before proceeding to the salesroom.

A laneway along one side of the site linked Conesford Street to the rear yard and continued on to the riverbank, where Toppes had a private wharf, called Mendham Staithe; another path from the wharf led to an archway entrance into the ground floor storeroom. He had doubtless selected this site for his business establishment partly because of its good access to river and road routes by which merchandize could conveniently reach his warehouse and showroom; but he must also have given careful thought to the potential for adaptation of the site and buildings to meet his mercantile needs, which included isolating behind-scenes activities involving movement of goods from the sales pitches going on in the great hall.

A model of Toppes' property, viewed from the south, showing:

at left, the main building, containing the long showroom, facing onto Conesford street;

ancillary buildings at rear; and at right the riverside wharf (here shown equipped with crane).

Photo © S. Alsford

Conesford Street was where a number of landed gentry families had town-houses, away from the noise and bustle of the city centre. Toppes probably rubbed shoulders with them, yet he did not live in his business establishment there, but rather showed his social affiliations by residing in his house near the Guildhall and marketplace. Yet he had the normal aspiration to improve his social standing, which he accomplished in part through his second marriage. He invested in rural estates around the county, including purchase of the manor of Hakon's at Great Melton; this gave him the right to a coat-of-arms, which he formed from the Hakon charge with three golden spinning tops (a play on his surname) added in the upper register.

Robert Toppes' first wife, Alice, may have been of similar mettle to her husband, for she was implicated with him and their son in an outburst of civic disorder in 1443, targeted at the prior of the cathedral priory, whose political machinations undermined the city government; it is unusual to find the wife of a civic leader so conspicuously involved in such matters, but the family was able to obtain a royal pardon. Alice died a few years later and Robert was now in a position to pursue a more prestigious wife (by 1451), in the person of Joan Knyvet, member of a gentry family. After Robert's death, she married the brother of Lord Roos, and they took up residence in Dragon Hall, but the family became embroiled in legal disputes over Toppe's will.

Between them, Toppes' two wives bore him two sons and six daughters; for those who survived long enough he sought socially improving marriages. The elder son married into a gentry family and focused on his role as lord of the manor inherited from his father. The eldest daughter, Agnes, married first an aging member of a leading Yarmouth family, William atte Fen, a merchant and former town bailiff, who held lands at Worstead; after the marriage William took up residence in Norwich, but died there in 1439 and Agnes remarried into a gentry family. As supervisors of his will Toppes named two members of the gentry with city ties: lawyers John Heydon (a former adherent of the Wetherby faction) and Sir William Yelverton. That he had no sentimental attachment to his trading hall, and no heir interested in carrying on his business, is indicated by his testamentary instruction for it to be sold to pay for masses for the souls of himself and his wife. Subsequent owners did not use it as a trading hall, and its features were hidden by later sub-division and under alterations to adapt the buildings to other uses, until its commercial character was rediscovered in the 1970s and later restored to turn it into a heritage site, commemorating the great cloth merchants of medieval Norwich.

Over the course of the medieval centuries the status of merchants within society

underwent a transition, from a peripheral position not even accommodated in the most

traditional conceptualization of the social hierarchy, and seen as morally suspect by

the Church, to one of greater respectability and indispensability as national economic,

social, and foreign policies became intertwined. A reflection of this process is seen in

the fourteenth century tombstone inscription of Richard Mercator, buried in a friary

at Lichfield; although now eroded to illegibility, the Latin, recorded by antiquarian

Theophilus Buckeridge was reported, along with his translation, in an issue of the

Gentleman's Magazine in 1746:

Richard the Merchant here extended lies,

Death, like a stepdame, gladly closed his eyes;

No more he trades beyond the burning zone,

But, happy, rests beneath the sacred stone;

His benefactions to the Church were great,

Tho' young, he hastened from this blest retreat;

May he, though dead, in trade successful prove

St. Michael's merchant in the realms above.