Model showing the port of Roman London

Photo © S. Alsford

Archaeological information (notably from excavations along Lower Thames Street) has permitted the Museum of London to reconstruct, as a model, what London's port may have looked like ca. A.D. 100. A sea-going ship is shown docked at quayside – the bridge across the Thames preventing it from proceeding further – and its cargo is being unloaded and moved into warehouses. At top of the picture the wharf is being extended further into the river by building a revetement and dumping earth and debris into it.

By that date London was already a bustling commercial centre, the vicinity of the waterfront, and many of its other streets, lined with shops, taverns, inns, and workshops. The Romans began the process of land reclamation from the river Thames, on which to build a quayside; this was developed in several phases, beginning upstream of London Bridge and proceeding down towards the Walbrook. London was an important trading port from the second to the early fifth centuries, with the city population consuming much of the merchandize imported, rather than it being stored for redistribution; this explains why archaeologists have identified only two warehouses associated with the port. The harbour facilities put in place by the Romans were the foundation for the medieval port; but the early Anglo-Saxon settlers relied on beaching their boats along the Strand, where they established their own settlement of Lundenwic west of the Roman city, then abandoned it following Viking raids of mid-ninth century. It was superseded by Alfred's Lundenburg, which had trade ties with Germany and northern France.

Part of modern London's quayside in front of Fishmongers' Hall

at the north-west corner of London Bridge; this part of what is now public quayside was

for some centuries a wharf reserved for the exclusive use of fishmongers.

.

Photo © S. Alsford

In the Late Middle Ages this stretch was known as Drynkwater's Wharf (possibly named after the owner of a tavern nearby) and there was a small inlet there known as Oystergate, where oyster catches were landed. West of the bridge was Queenhithe, London's main public quay for much of the MIddle Ages. A market developed at the hythe for fish, grain, and salt cargoes unloaded there, so that in 1471 the Fishmongers Company was willing to foot the bill to enlarge the dock. On the east side of the bridge was Fishwharf, where a number of fishmongers had shops, followed by a series of private wharves and communal quayside leading up to Billingsgate, which acquired importance as both harbour and market in the fifteenth century, for goods that included oysters but not yet fish. However, sales of fish were not confined to Thameside, but took place in several other markets in the city, including two dedicated to fish.

The fishmongers had organized themselves into a collective at relatively early date, acquired for gild members a monopoly on sales of fish, and had a meeting hall before 1310, possibly in Bridge Street where they were said to hold their hallmoots to administer the trade. They were a numerous, wealthy, and sometimes turbulent interest group much involved in city politics (not least during the factionalism of Richard II's reign), and also a mercantile occupation requiring careful supervision, since their merchandize had so important a place in the medieval diet. City regulations prohibited fishmongers from taking their boats up- or down-river to intercept fishing vessels before their catches could be brought to the city quayside, where tolls could be collected. The company's monopoly on the fish trade was gradually undermined from the fifteenth century.

The Fishmongers' Company's current meeting hall, next to the end of London Bridge, is a neo-classical design (the arcades at wharf level echoing the Roman acqueduct style of London bridge) built in the 1830s. It stands on part of a site created through amalgamation, following mid-fifteenth century acquisition by the Company of a cluster of adjacent tenements forming a long tract of ground stretching between the river and that part of Thames Street which had become known as Stockfishmongers Row, with the eastern-most tenement facing onto Bridge Street, where there was a fishmarket; further north, Bridge Street became New Fish Street.

These tenements had lengthened over time as land was reclaimed from the river and warehouses and quays were added there, and most had at some time been residences of citizens such as three-time mayor John Lovekyn (d.1368) and other leading fishmongers of medieval London. At the river end of the tenement formerly belonging to Lovekyn stood a hall that was acquired by the fishmongers, in much the same location as the present one, and nearby the smaller hall of the stockfishmongers (a separate branch of the trade until the Tudor period), also in an existing building; both were destroyed by the fire of 1666.

If London has consistenly been, throughout its history, England's leading port, at the other end of the scale are places like Tewkesbury, which had a rather shorter spell in the sun. Tewkesbury quayside is today a modest facility serving mainly pleasure craft, but in the Late Middle Ages Tewkesbury was the second most important town in Gloucestershire, and its busy river port, at the confluence of the Severn and Avon, was one of the furthest inland. Most of its traffic was along the Severn, the Avon being less navigable.

Facilities for pleasure craft along part of the Avon, near the

end of Quay Street, Tewkesbury.

Photo © S. Alsford

Early settlement at the site of Tewkesbury (from prehistoric times through the Roman period), though perhaps patchy, was on islands of river gravel between a branch of the Avon and the River Swilgate, primarily in a neighbourhood later known as Oldbury; surrounding land was susceptible to flooding. Settlement later extended along a Roman north-south route paralleling the bank of the Severn, at a point near a crossing of the Avon; still later, a small Benedictine priory of Anglo-Saxon origins became a focus of the developing settlement, at the expense of Oldbury, which by the twelfth century had become an open field. The manor of Tewkesbury was already associated with a modest borough by the time of Domesday, which mentions 13 burgesses, a market, mills, and a fishery; the market received royal approval from William I's queen, but may have existed informally at earlier date.

The manor and its appurtenances came into the hands of the father-in-law of the future first earl of Gloucester ca.1087; in 1102 he refounded the Anglo-Saxon abbey, and the earls who succeeded him as lord of Tewkesbury granted the typical borough privileges (known from a confirmation of 1314) that gave residents incentive to develop trades or crafts to generate income; a custumal, believed to date to the twelfth century but known only through a copy, reiterates and expands on these privileges. The basic advantages accorded to Tewkesbury's burgesses, free of any feudal dues or need for seigneurial licence, included a fixed burgage rent and the right freely to own and dispose of real property, the freedom to bake bread and brew ale and sell the product, and exemption from tolls throughout the earl's estates; while all land-holders of the local hundred, burgess or not, could sell their own produce or buy household needs in the marketplace free of toll, so long as not purchasing to re-sell (although all merchandize valued under fourpence was toll-exempt). Stallage fees were limited to a farthing, so long as no more than two merchants shared use of the stall. By 1199 the earl owned a fair on his manor at Tewkesbury, and a second fair, for mid-summer, was licensed in the 1320s but in 1441 replaced by two fairs held in February and August. The new abbey must have provided a strong economic stimulus for the town, for it was a sizable and relatively wealthy monastic community in need of victuals, clothing, and other goods and services; furthermore, by the fifteenth century, and perhaps earlier, it was serving as the parish church for the townspeople.

Tewkesbury's market was held twice a week, and the tolls from this commerce were, by grant of King John, put towards maintenance of a bridge over the Avon whose construction the king sponsored; the marketplace was originally at a point on the High Street where other roads merged, but gradually spread out along the street. By 1327 we hear of 114 burgesses living there, and the trade of the town was flourishing. The names of the burgesses at that time suggest a wide range of occupations, notably men involved in cloth and leather industries, but also including goldsmith, glazier, and spicer (all suggestive of abbey custom); from other sources we hear of innkeepers, vintners (possibly working the abbey vineyards), and the usual victualling trades, as well as cutlers, ironmongers, bellfounders, and braziers. Wide windows seen in a number of surviving fifteenth and sixteenth century buildings (with which Tewkesbury is well-endowed) also suggest the importance of cloth-making, which needed good light.

Although Gloucester dominated the river trade, Tewkesbury was in competition and by the late sixteenth century was home to nine cargo boats, averaging 15 tons burden. During the Late Middle Ages, livestock, iron, and linen were among known goods traded, and part of the town's commerce invoved shipping down to Bristol grain, malt, and hay produced in the surrounding countryside, along with cloth and leather goods manufactured locally; some Tewkesbury townsmen even received licences to ship grain overseas. Boat-building is also evidenced, and in 1401 Tewkesbury was one of the towns each required to produce a barge for royal military use. In 1519 we hear of the funding of repairs to the town quay on the Avon.

Between the extremes of London and Tewkesbury were numerous coastal, estuary-based, and riverine port towns attempting to maintain themselves in competition for a share of maritime trade. Most of those significant in the Middle Ages were on or close to the southern and eastern coasts of England. The Cinque Ports are a well-known example of towns of modest size to which the narrow Channel separating England from north-western Europe brought both benefits and vulnerabilities.

In an age when Rye was much more accessible from the sea,

the Ypres Tower was built as part of a defensive system to protect the town from

French raiders. Today the tower offers a view down towards the River Rother,

and the channel connecting it to the River Tillingham, meandering some distance

before it reaches the sea.

Photo © S. Alsford

Although today Rye is some two miles distant from the sea, it was through much of the Middle Ages a sea-port and a centre of fishing, ship-building, and maritime commerce (both coastal and international), not to mention piracy and smuggling. The River Brede, linking the sea to the interior, passed by it. One of the towns added by Henry II, as associate members, to the original membership of the Cinque Ports, Rye was from the early fourteenth century a head port of that confederation in its own right. The town was built atop what was essentially an island in the mouth of the Tillingham, facing out onto a wide area of marshes and mud flats that opened to the sea; across this bay a wide shingle bank, created by tidal drift, offered a partial barrier to the tides. Just north of the site of Rye the Rother ran into the sea, and slightly south so did the Brede, a wide river with good access into the Sussex Weald. The rocky promontory on which Rye was founded might conceivably have been an early trading spot, and perhaps even meeting-place of the hundred.

However, Rye's growth of importance as a port owes more to the post-Conquest re-orientation of trade towards northern France. It likely originated as a new town founded in the late eleventh century on a manor belonging to Fécamp Abbey, the monks' intention perhaps being to market and export the output of manorial saltpans, as well as tap into local fishing and provide a new channel for export of Wealden iron, timber, and other resources [Gillian Draper, Rye: A History of a Sussex Cinque Port to 1660, Chichester: Phillimore, 2009, 13].

The ability to exploit this trade potential owed much to the changes along the sea-coast. Breaches in the shingle barrier were already appearing by the eleventh century, exposing the river mouths to tidal effects. As the breach nearest Rye enlarged, tidal influx, combined with the digging of fleets as part of marsh reclamation, created deeper water conditions at the mouth of the Brede, making it a haven deep enough for sea-going ships to anchor. Over the course of the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, rising sea level and a series of worsening storms, which destroyed the nearby town of Old Winchelsea and further breached the shinglebank, also altered the course of the Rother towards Rye (whose tidal current ate away part of Rye) and caused the navigable passage along the Brede to narrow and become shallow. Thereafter Rye's main harbour was in the area known as the Strand, along the Tillingham, but steady silting via the Rother, exacerbated by the consequences of further marsh reclamation, led to the gradual deterioration of the Rother and Tillingham, and consequently Rye's port, after the Tudor period. Furthemore, timber from Rye's hinterland, essential for its ship-building industry, became scarcer, whilst the adaptation of ship design to the introduction of cannon demanded deep-draught ships that could not be built in Rye's shallowing waters.

Part of the Strand quayside, with boats stranded along

the River Tillingham at low tide.

Photo © S. Alsford

Despite intermittent efforts to rectify the silting problem, Rye's value as a port, for anything other than fishing, declined, although modern improvements have kept a local fishing industry alive and support recreational watercraft use.

Apart from docks themselves, one facility needed by any port where bulk goods were being imported and exported was warehousing. Warehouses became one of the principal architectural characteristics of ports in the post-medieval period. It is not clear that the same can be said for the medieval period, however, for warehouses of that period are a type of structure not yet well investigated. There are a number of reasons for this. Medieval records of property transactions often do not specify the function of buildings involved. Much of the space for storing merchandize was built into residential properties, in the form of cellars, back rooms, or subsidiary structures in the rear yard. Custom-built warehouses were probably fewer than they became later and, from their nature, were more prone to subsequent demolition and replacement rather than renovation; so they have left fewer unambiguous architectural or archaeological traces. But this does not mean we should conclude, as some have, that warehouses, in the sense of buildings constructed specifically and exclusively for storing merchandize, were a post-medieval introduction due to continental influence. There are a few rare survivals of buildings that are known, or believed, to have been built in England for such a purpose.

The Wool House at Southampton.

Photo © S. Alsford

Until recently housing Southampton's maritime museum, the stone structure shown above was built ca.1400, as the Wool House, a two-storey warehouse to store wool intended for shipping to Flanders and Italy. Other warehouses are heard of in Southampton, but none has survived, and the Wool House may possibly have replaced or renovated an older warehouse on the site. The buttresses are additions, and the windows and doorway replacements, of post-medieval times; but the doorway represents the original location and the interior roof bracing is fourteenth century.

Located at the southern end of town, about midway between the south and west quays, the Wool House faced the Wool Bridge, a through route for wool to be shipped from the quayside and a place where wool transactions occurred. An enquiry in 1407, pursuant to a request by the local customs collectors, into the best place to locate the king's weigh-beam, which was used to assess customs on exports, confirmed the placement (already implemented the previous year) of a building newly constructed by Thomas Middleton opposite the Wool Bridge, and this quite possibly was the Wool House [so argues Colin Platt, Medieval Southampton, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973, p.142]. However, the owner of an older building, less conveniently situated, on the grounds of a life grant of custody of the trone, successfully petitioned for its return in 1410, despite some suspicion that the traditional site (known as the Weigh House) had facilitated embezzlement of customs proceeds in the past. About the same time Middleton was financing the expansion of the southern quay facilities (equipped with crane) near the Watergate, equidistant from the Weigh House and the Wool House and connected to the latter via Porters Lane; this improvement was (it was argued) to facilitate the loading and unloading of cargoes of visiting merchants, at the cost of new duties payable in the form of wharfage and cranage. Middleton's investment was recouped from a life grant to him of those duties. Winchester's merchants resisted the new levies at first, until the king approved them in 1411.

We also know of a Wool House at Kingston-upon-Hull, built ca.1389 (again possibly replacing an earlier structure). Before the close of the fifteenth century it had been expanded to take on additional functions, such as customs collection, an entry arcade where merchants could presumably meet and discuss business, and housing for a weigh-beam and communal crane, as well as storage space that could be rented to visiting merchants. It was rebuilt in 1620. At Ipswich one item in the chamberlains' accounts of 1464 was payment for adjustments to the weights kept in the Wool House, and ten years later further adjustment was made to bring the wool weights into concordance with London standards.

If we know relatively little about medieval warehouses, we know even less about English cranes and weigh-beams beyond that they seem also to have been common features, at least at the more important ports, in the Late Middle Ages. For cranes we rely largely on artists' renderings of them, plus a few examples that have survived within the fabric of churches such as a fifteenth-century crane in Canterbury cathedral. The Flemish miniaturist Simon Bening (1483-1561) has left us a painting of the wine market in central Bruges where a huge crane is lifting tuns of wine; Bening, who was a great observer of details, shows the crane powered by a human treadmill – or more likely, given the number of men shown, a pair of treadmills operating together side-by-side; the crane mechanism was enclosed in housing to shelter it from the elements.

(above) This landscape by Simon Bening represents October

(month of the wine harvest) in one of his "Labours of the months"series, and shows

the wine market in central Bruges and its crane.

(below)A smaller version of the treadwheel crane, with a single-occupant tradwheel;

such a treadwheel about twice the height of a man would give the lifting power of

ten men or more.

From a fifteenth century French copy

of William of Tyre's Histoire d'Outremer,

British Library

This technology, known to have been used in the Ancient World for construction projects, reappeared in Europe around the early thirteenth century and was being applied to harbour uses by Flemish and Hanseatic League towns a little later in the century; it from is within the former territory of the Hanse that a few examples have survived, such as the Crane Gate on the Gdansk quayside, an even larger version than the Bruges crane, built into a stone tower to give it more stability. Where information is available about them, these harbour cranes used two treadwheels; this was not because they needed to lift heavier items than construction cranes, but because loading and unloading ships, particularly in a busy port, required speedier operation than building construction. Smaller versions of the treadwheel type of crane are also known, while other medieval illustrations show cranes of the windlass type. We do not have enough information about cranes used at English harbours to be certain if they were of the treadmill or windlass type, or even some simpler winch or see-saw mechanism; but it seems likely they were modelled on continental versions. At small ports goods may have continued to be loaded and unloaded by pure manual labour, using ramps between wharf and ship.

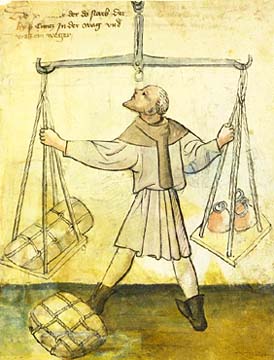

Kunz in der Waag was a weigher, or gauger, at Nuremberg in

the early fifteenth century, probably a civic employee, as his surname connects him

to the official weigh-house; he retired to a home where this portrait was made upon

his death there. He is depicted using the city's great beam and three large weights

to determine, for customs purposes, the weight of bales of merchandize.

From the Hausbuch der Mendelschen Zwölfbrüderstiftung

While anyshopkeeper retailing goods by weight must have had his own balance, wholesale goods for import and export were supposed to be weighed on a communal weigh-beam, or trone, by an officer responsible for the task. Private weigh-beams met with disapproval from municipal authorities; in 1466, for example, an Ipswich innkeeper was fined for having a weigh-beam in his inn – a reflection of the volume of private trading that could go on at such places. Communal weigh-beams seem to have been present at or near quaysides and major marketplaces; in some towns, such as Southampton, Winchester, and Hull, they were kept in proximity to places where wool bales were stored, that being one of the principal kinds of goods requiring their use.