Successful military service could bring titles, lands, wealth, and prestige, but it also entailed risks. The Beauchamp earls of Warwick provide an example of a family whose military proclivities brought them ups and downs.

Tombs of several of the earls of Warwick were in the collegiate

church of St. Mary, Warwick. The college was founded by one of the

twelfth century earls and its priests were subsequently transferred

to St. Mary's, which had probably existed before the Conquest.

(above) The alabaster tomb effigy of Thomas I, who initiated

the rebuilding of St. Mary's, a project completed by Thomas II.

(below) The gilded brass effigy of Richard Beauchamp lies in a

richly decorated chantry

chapel built at great expense to house his tomb. Both men are shown

in the armour they wore in the service of their kings.

Photos © S. Alsford

Thomas I de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick (1313-1369), was one of the original Knights of the Garter and Marshall of England from 1343 until his death. One of Edward III's commanders during the Hundred Years War, he played a role in the victory at Crecy and, after acting as guardian of the teen-aged Black Prince, fought alongside him at the battle of Poitiers. He was participating in the siege of Calais when he died, of plague. His plan to rebuild St. Mary's church was financed from the ransom of a French archbishop. His son, Thomas II, succeeded him as earl and in the duties as a commander in France, yet in the next reign fell foul of the king, as one of the Lords Appellant, and was banished. Later convicted of treason, he was sentenced to death, but reprieved when Henry IV seized the throne.

Richard Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick (1382-1439), followed in the family tradition of military service. Soon after coming of age and taking up the earldom (1403), he had to defend against a Welsh rebellion, and he fought for the king against Harry Hotspur's rebels at the battle of Shrewsbury. The following year he took the offensive, repulsed an opposing Welsh force and almost captured its leader, Glendower. He acquired a reputation for his prowess in combat and his chivalric deeds. In 1414 he helped put down the Lollard uprising and spent the next few years as a military commander in France, heing rewarded in 1419 with the title Count of Aumale. In 1425 he was appointed acting regent of France and pursued the war effort by capturing several strongholds. His value to the Crown is reflected in him being given, after Henry V's death, responsibility for the infant Henry VI's education, he dividing his time between that and his duties in France. In 1437 he was once more made regent in France, but two years into his term fell sick and died at the castle of Rouen.

While members of the nobility might enhance their status and enrich themselves through their military exploits, very few townsmen were involved so directly in military command. For some of them, however, war could also be an avenue to royal favour and substantial profits. To wage war was expensive and taxation – the primary source of public funding of war efforts – was slow to realize revenues. However, merchants were a ready source of cash and some were willing to take the risks of slow or no repayment in order to have kings indebted to them. It may be argued that the principal contribution of the towns to national defence was in financing it. Leading merchants from London and other large towns, made individual or group loans to enable kings to pay their war costs, or provided business expertise to manage customs revenues in a fashion that furnished the king with cash in a timely manner.

Memorials to two prominent townsmen whose wealth

was put to the service of the king.

(left) A modern statue (1991, by Anthony Griffiths) of John le Fleming

stands gazing out over a stretch of parapet on Southampton's wall,

between the Arundel Tower and and the

Bargate,

which can be seen beyond the statue.

(right) The famous

Richard Whittington

owed his success to no small degree to his role as a financier.

It is appropriate therefore that the statue (1844) of Whittington

was placed in the facade of the Royal Exchange in London.

Photos © S. Alsford

One merchant who assisted the war effort was John le Fleming of Southampton. In 1295 the town built Edward I a galley – one of a fleet commissioned for the French war. Once built, John bought for it cables, hawsers, and stays, furnished it with an oven and cooking utensils, as well as containers for food and drink, and paid the costs of its crew (master, three constables, and 120 sailors) on a four-day journey to Winchelsea to join up with the fleet. He also supplied the crew with helmets, body armour, 60 crossbows (with 16,000 quarrels), 120 spears, 240 javelins, and 100 halberds. Descendant of a leading townsman of an earlier generation (Walter le Fleming, ship-owner, town bailiff, and royal commissioner) John went on to serve as Southampton's mayor in 1319/20 and to represent it in seven parliaments; he owned several urban and suburban properties, including a windmill, and acted as business agent for religious houses.

Profit on a more modest scale than the financiers, but with less risk incurred, was made by a larger number of townsmen involved in supplying army or navy with raw materials such as foodstuffs, manufactured products such as shipping containers, weapons and armour, or services such as transportation. War also provided employment for ancillary services required to support military efforts; in 1414, for example, for his expedition to France Henry V aimed to engage (by impressment) 100 masons, 120 carpenters, 40 smiths, and 60 carters, and he was also accompanied by at least 14 minstrels and a surgical staff of about the same size.

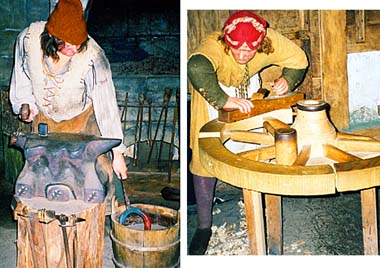

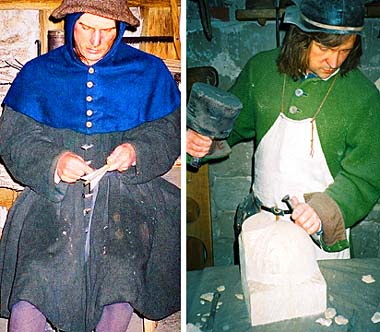

Dioramas from the Kingmaker exhibition at Warwick castle show some of

the craftsmen for whom war meant employment opportunities.

(above)Blacksmiths kept warhorses shod, while wheelwrights kept the

supply train wagons rolling.

(below) Fletchers prepared large supplies of arrows (here glueing feathers

to one end of a shaft)l, while masons cut cannon-balls from stone blocks.

Photos © S. Alsford

But while a state of war meant profits for some, for others the jeopardy of enemy attack meant exposure to financial loss – whether in terms of destruction of real estate, plunder of possessions, or capture of mercantile cargoes – or to personal danger, in terms of loss of life, limb, or liberty. Townsmen who died in wartime were not commemorated as magnificently as the Beauchamps, and many probably ended up in mass, unmarked graves.

The Battle of Tewkesbury left so many dead on the field that one part of

the battleground has ever thereafter been known as Bloody Meadow.

Photo © S. Alsford