History of

medieval Lynn

History of

medieval Lynn History of

medieval Lynn

History of

medieval Lynn

| Buildings and fortifications |

When fortifications were created around the town it was initially along the line of the existing sea bank, by this time well east of the actual line of the riverbank. Since the built-up area of the town was in the eastern half of the territory between the river and the sea bank (i.e. concentrated closest to the river), there was land available in the western half for pastures, orchards, mills, or for the monastic complexes of the various orders of friars which established themselves in Lynn in the thirteenth century. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, progressive reclamation of land from the river (by silting, dumping of refuse, and building over the river edge) allowed wealthy merchants to establish their complexes along the westward-shifting river's edge or along the banks of the Millfleet or Purfleet, which gave access to and from the river. A few of the later examples survive today and are among the architectural treasures which give parts of modern King's Lynn a sense of the town at the close of the Middle Ages.

Some surviving ecclesiastical architecture

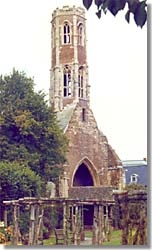

[left] A 15th century tower of the Franciscan friary;

the Franciscans established themselves in Lynn in the 1260s,

occupying a site between St. Margaret's and St. James'.

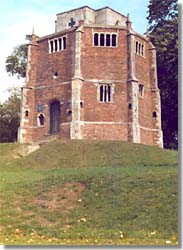

[right] The Chapel of Our Lady at the Mount

(commonly known as Red Mount), built 1485,

lay just outside the eastern defensive perimeter.

photos © S. Alsford

For many townsmen a single property served as the owner's home and place of business. A merchant complex was typically a long and narrow plot of land on which was built a combination of residence, shop, warehouse and private quay; sometimes the property was divided by a street, so that the quay and associated buildings were adjacent to the water while the residence was on the opposite side of the street, but in most cases all the buildings lay between street and waterway. Plots usually had their narrower side facing the street; this side might be up to 50 feet wide in the thirteenth century, but by the fifteenth when there was greater demand for frontage (at least in certain parts of the town) 30 feet was a more normal width. However, despite some measure of planned creation of the town, there is no evidence of an attempt at any time to standardize the size of building plots. The largest holdings might take the following layout:

Thoresby College doorway

The college was built ca.1510, a testamentary

foundation of Thomas Thoresby, sometime mayor

and member of a leading burgess family. The style

of the doorway is very similar to those of the

15th century.

photo © S. Alsford

More moderately sized properties – particularly those elsewhere than the waterfront, and particularly as street frontage was reduced in width towards the end of the Middle Ages – owned by lesser merchants or well-to-do craftsmen might comprise one or more retail shops and/or industrial workshops facing the street, with living quarters above; often as a later addition, halls were built behind the shop/solar and more utilitarian structures further back, with a narrow passageway leading off the street, under the front range of buildings, and down one side of the plot to give access to the structures further back. Lesser craftsmen or retailers would probably have made do with just a shop/solar structure. Since dwellings of the poorer townspeople were the most likely to be of flimsy construction, subject to deterioration and later replacement, we know little of the living conditions of that group, although documents refer to cottages which were probably small, single-room residences of the lower strata of borough society.

Another part of King's Lynn's architectural heritage are two of the halls built by medieval gilds of the town, along with the buildings serving as the base for the Hanse merchants in Lynn, known as the steelyard. The gilds, as organized instruments of interest groups within the community, played an important part in building and/or maintaining public facilities. Most striking is the hall of Holy Trinity Gild, which was apparently the successor to the Merchant Gild authorized by the 1204 charter. By the late thirteenth century it had a meeting hall in the Saturday Market, naturally enough, near St. Margaret's. This was gutted by fire in 1421 and a new hall was constructed (using brick) at a different location, in the northwestern corner of the market; the Gild spent over £200 on this project during the following two years. The side facing out into the market was decorated with a chequered pattern of black and white squares of flint and a large arched window. The hall was used not only by Trinity Gild but rented for meetings by other gilds and by the borough corporation (which by the 1360s was employing a caretaker of the gildhall, who also served as bedeman, an office involving public announcement of the death of Gild members – this being an indicator of the close link of Gild and borough). Trinity Gild had a significant role in the life of the community, not only by representing the interests of most leading members of that community (the merchants), nor only by its traditional association with town government, but also by its management of the Common Staith, its provision of charitable services, its contributions to maintenance of public facilities (e.g. water conduits) and churches, and the availability of its treasury for commercial or public loans.

Holy Trinity Gildhall

(facade on the northwest corner

of the Saturday market),

the seat of medieval borough government.

photo © S. Alsford

For an artist's impression of how the

Guildhall might have looked when first

built, see

here

Both Trinity Gild and the Bishop contributed to the construction of Lynn's defences, which were as much to control the access-points of traders into the town and to define the area of borough jurisdiction as to protect from attack. The sea bank pre-existing the town provided a natural line of defence and was made more effective by digging a ditch on its outward-facing (east) side; the ditch later became part of the canal system. There is evidence for a lesser ditch on the townward side of the bank, although this may have been only to furnish soil to raise the bank. This activity is suspected to have taken place in the context of the civil war at the close of the reign of King John, when Lynn appears to have experienced a direct threat. There were also four wooden towers: two stood at the southern and northern ends of the Newland river bank (thus also guarding the entrances to the Purfleet and the Gay, respectively), and the other two likely at the northern and southern ends of the ditch/bank guarding the east-west road into Newland and the south-north road into South Lynn respectively; their date of creation is uncertain, although the Bishop's Bretask (the tower by the Gay) is heard of by 1270.

Royal grants of murage were obtained by Lynn in 1266, 1294, 1300 and 1339, the baronial wars doubtless providing the first impetus for upgrading defences to a stone wall. Wall construction began on the eastern boundary of Newland, with a stone gate built where the east-west road and the wall intersected. The question of boundary definition was another point on which town authorities and the Bishop – through his tenants of the adjacent manor of Gaywood – came into dispute. The townsmen had used the wall to extend their boundary eastwards beyond the earlier line of the sea bank, in order to encompass a suburb which had arisen east of the bank. The southern entrance to Lynn, through South Lynn, was likewise strengthened with a stone gate before 1319. The South Gate and East Gate, possibly successors to bretasks on those sites (certainly in the late 1360s a connection is made in the borough records between the south gates and a South Bretask), had gatekeepers in the Late Middle Ages and were seen as the main entrances to the town; other gates lying between these two, probably built in the same period, were secondary points of access into the town, and were kept locked at night. The stone wall was not extended south from Newland, to protect central and South Lynn, until the post-medieval period. Various of the watercourses already mentioned were part of the town's defensive system. The River Gay was the town's northern boundary and defence; a gatekeeper was less regularly employed by the borough for a gate guarding the bridge across the Gay, at Dowshill.

previous |

main menu |

next |

| Created: August 29, 1998. Last update: January 1, 2008 | © Stephen Alsford, 1998-2008 |