History of

medieval Yarmouth

History of

medieval Yarmouth History of

medieval Yarmouth

History of

medieval Yarmouth

| Origins and early growth |

In the medieval mind, Yarmouth was associated with herring, a high-protein food important to the diet of the lower classes, which featured less meat than is eaten today. The thirteenth century seal of the borough bore depictions of a ship sailing herring-inhabited waters and, on the other side, St. Nicholas, a patron saint of fishermen. The fishery provided the reason for Yarmouth's foundation and the principal source of its medieval economy.

Great Yarmouth – the qualifier distinguishing it from its southern neighbour, Little Yarmouth – is situated near where several rivers, among them the Yare, flow into what was once a very broad estuary (much larger than the present-day Breydon Water) opening out into the sea. In Roman times there was a port and market town a little further north, at Caistor, and a small fort inland at Burgh Castle; these were later abandoned. Subsequent settlement focused on the site of Great Yarmouth itself. Tradition has the first settlement there established by the Saxon leader, Cerdic, ca. 495, but this is unsubstantiated and doubtful. More certain is that silting in the mouth of the "Great Estuary" over time formed a huge sandbank that came to be several miles long, with breaches leaving the Yare access into the sea through two channels at either end of the sandbank; one channel separated Yarmouth and Caister, the other ran southwards for some miles and separated Great and Little Yarmouth/Gorleston before entering the sea. The name Yarmouth is doubtless associated with that of the river, a connection dating back to at least late Roman times (when Gariannonor, or variants, was applied to a base in the vicinity, perhaps Caister), although possibly both river and town names heark back to a Germanic term for 'promontory', suggestive of the sand-spit. [1]

This sand-spit, just a few feet above sea level and effectively an island, eventually became firm enough to support dwellings, perhaps preceded by more temporary encampment facilities for the drying, salting and smoking of herring, as well as the sale of herring. There may have been settlers as early as the tenth century, although probably transients; the ground level rose as the wind blew sand across the site and buried rubbish and debris accumulated from human habitation. Fishermen from the Cinque Ports claimed a long-standing right to beach their boats and to dry their nets there. A fair may have been in operation there by the time of Edward the Confessor, during the forty days from Michaelmas to Martinmas when the fishery was at its peak; in later times this important fair attracted not only the Cinque Ports men, but also fishermen from the continent. The Cinque Ports had authority over the fair, through officers they appointed, which was subsequently resisted and then contested by Yarmouth. Another indication that Cinque Ports fishermen were likely among the founders of the town is that rents from some Yarmouth properties were due to the Ports.

Yarmouth was a borough in the royal domain before and at the time of the Domesday survey, but an earlier shared jurisdiction is reflected in that Yarmouth had to pay every "third penny" of all public revenues (e.g. tolls and rents) to the earl. The number of burgesses living there – 70 in 1066 according to Domesday – suggests that its fishery was already important by this date, the 24 residents explicitly identified as fishermen only being those attached to the manor of Gorleston. But Yarmouth was a small town compared to Norwich or Ipswich, with a few hundred residents in all. As a "frontier town" it had no important role in regional administration; the king never licensed a mint there. Domesday noted one church there, dedicated to St. Benedict.

Early settlement appears to have focused on the most elevated part of the sandbank, near the northern channel, along the western edge of what would become the marketplace. There is archaeological evidence of simple structures from the early eleventh century, and more permanent houses by the twelfth. In 1101 the Bishop of Norwich built a chapel in that neighbourhood (superseding a more modest building on the beach intended to celebrate divine service during the fishing season) and, in the 1120s founded St. Nicholas' church by the northern channel; a Benedictine cell of the Norwich cathedral-priory was established in association with St. Nicholas'. This became the parish church, and the site of St. Benedict's is now unknown -- ruins of some ecclesiastical structure may have been that church or a chapel built by the Cinque Ports men in the mid-eleventh century (after a dispute with the bishop over the advowson of the earlier chapel). South of St. Nicholas' lay the site of the borough marketplace, perhaps originally stretching east-west across the width of the town from the river channel to the beach facing the sea, although over the course of the Middle Ages the original shape of the market was obscured as parts were built upon – including the hypothetical western section, but also a large chunk on the eastern side was consumed by the foundation of St. Mary's Hospital. By the opening of the fourteenth century settlement had spread further west, as a result of gradual reclamation of river shoreline following the construction and extensions of a wooden quayside there (a Franciscan friary being built on what had earlier been riverbank).

The town suffered from progressive silting of parts of the channels used as havens for ships; this became a major challenge and expense for the borough government throughout the later medieval period. Silting of the northern channel, to the point where it was unusable, subsequently encouraged population to expand southwards along the line of the southern-running channel and to relocate the haven in this channel. The bank of this channel became lined with quays, in contrast to the opposite side of the town – the great beachy area, or "Denes" (dunes?) facing the sea, on which would have been visible fishing-boats, nets stretched out to dry, and windmills. Although the section around St. Nicholas had been abandoned by most residents when wall construction was begun, the church itself remained important to the town; a major expansion was undertaken shortly before the mid-fourteenth century. Consequently, the line of the town wall was extended just far enough north to encompass the church. The southern channel too, however, experienced problems and at various times in the Late Middle Ages the townsmen had to cut new harbours.

| Development of local government |

In the twelfth century we have mentions of a reeve as the governing authority of Yarmouth, but this was an officer appointed by the king. In 1208, the king leased to the town (in return for a fee farm of £55) its first powers of self-administration; the royal charter granted:

When, in the 1220s, holders of the borough executive office begin to be identified, we see there to be 4 bailiffs, elected annually, rather than the earlier single reeve. This multiplication is probably associated with the fact that the town was divided into four "leets" (wards) for administrative purposes. Unlike in Norwich, where the leets reflected early settlements that coalesced into one city, there seems no special rationale in the Yarmouth divisions; the original boundaries are unknown and the names indicate a straightforward division of the town into northern and southern halves, each of which was in turn subdivided.

Political conflict in or shortly before 1272, serious enough to have become violent, resulted in a set of reform ordinances which included the introduction of a town council to assist the bailiffs in governing Yarmouth. A few years later, officers responsible for the borough treasury (known as "the pyx") – its safeguard and the deposit and withdrawal of funds – were introduced. In 1426 we see further constitutional changes, as the balance of power within the community shifted from democracy to oligarchy; the number of bailiffs was reduced, a second-tier council was created, and chamberlains were put in charge of borough finance. Lesser officials of Yarmouth's administration included, in addition to the usual town clerk and sergeants (or sub-bailiffs), a water-bailiff involved in the collection of customs at the port, and occasionally officers (muragers) responsible for supervising the building of town walls and collecting the revenues to support that activity (later the chamberlains took over the collecting duty).

Although local leaders might at first have met in private houses, the parish church, or the open air, as seems often the case in early boroughs, the first known centre of medieval administration was the Tolhouse, (which still stands today), the site of the borough court and gaol. Located on the slight ridge thought to have been the earliest area of settlement, it was sturdily built around the second half of the twelfth century as a merchant's residence and enlarged about a century later, before the borough began leasing it for civic uses in the fourteenth century. The building must have been too small for community assemblies and we hear in mid-fourteenth century of a "common hall", which may have been the same as the sixteenth-century Guildhall on the south side of St. Nicholas' churchyard.

The Tolhouse

Note the grill (below), which

allowed prisoners in the gaol to

beg necessaries from passers-by.

photos © S. Alsford

The borough court sat each Monday to deal with civil pleas, most criminal pleas being reserved for the borough coroners or the king's courts. As the volume of business increased, sessions were extended to other days and some specialization – such as in legal transactions dealing with real estate or debt – began to take place, although this ceased when court business dropped off in the fifteenth century. One day each June was dedicated to hearing presentments from each of the leet courts. Cases involving visiting merchants from other places might be held on any day, in order to render swift justice. During the annual fair, court sessions were held daily rather than weekly – again reflecting the need for quick resolution of commercial disputes; these sessions were, at least by 1277, presided over jointly by Yarmouth's bailiffs and those representing the Cinque Ports, although perhaps previously by the latter only. The Cinque Ports bailiffs had been given by the king, in 1215, the right to administer justice in cases involving their fellow townsmen while in Yarmouth, and Hastings had (or claimed) an even older legal jurisdiction there.

The jurisdiction of Cinque Ports bailiffs during the time of the herring fair did not sit well with the Yarmouth authorities, and relations with the Cinque Ports were frequently quarrelsome – if not violent – in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. Following the suppression in 1265 of de Montfort's rebellion, which the Cinque Ports had supported, Henry III showed some favour to Yarmouth, but in 1272 disturbances in the town and Yarmouth's role in the Norwich riots counteracted this. In 1277, after complaints from Yarmouth, Edward I intervened to impose a compromise involving shared jurisdiction. But this proved no solution, and there were repeated mediations, attempts at settlements, as well as fines for breaches of the peace during the reign of Edward I. At one point the Yarmouth and Cinque Ports contingents of a royal fleet set to fighting each other, with the loss of at least 25 Yarmouth ships resulting. In 1300, Yarmouth's administration passed ordinances attempting to regulate the fair; for example, they specified that townsmen should be appointed to assess the quality of goods offered for sale. By 1314, the Yarmouth authorities were so much in the ascendant that it was the Portsmen's turn to seek the king's support for their jurisdictional rights at the fair. By 1316, matters had deteriorated to the point where the sides were preparing fleets to attack each other. The Cinque Ports' rights were confirmed by Edward III in the Statute of Herring (1357), which revealed the extent of Yarmouth's control over the fishery. The quarrel between the two sides gradually quietened, as they refocused their hostilities against a common enemy, France, but was not finally resolved until the Tudor period.

Yarmouth also turned its attentions to another rival. The constant silting up of Yarmouth's harbour, combined with merchants' desire to avoid paying borough customs, was during the second half of the fourteenth century prompting ships to land goods at Kirkley Road in the Lowestoft area. Using the argument that the town had become depopulated and impoverished and its ability to defend the coast as well as its financial obligations to the king were in jeopardy, Yarmouth successfully petitioned Edward III to annex this haven and to prohibit loading or unloading of cargo (or the holding of a rival fair) anywhere else within a seven-mile radius (1372); the king added £5 to the town's fee farm as payment for this extended jurisdiction. Naturally, Lowestoft was not pleased about this. The Yarmouth-Lowestoft struggle became a factor in national politics: the king (who had to be concerned about the supply of herring as well as the viability of Yarmouth as an element in coastal defence) was largely sympathetic, but parliament was hostile to Yarmouth and repealed the annexation in 1376. However, Yarmouth managed to obtain the patronage of John of Gaunt and overturn the repeal. For some years the matter went back and forth, with repeals and restorations, ending eventually in a compromise in 1401.

The interminable and largely insoluble disputes with the Cinque Ports and Lowestoft were fairly typical manifestations in a medieval town seeking to define and expand its authority. Similar rivalries found expression with Norwich, a long-standing competitor for trade using the River Yare, and through a drawn-out legal battle with Little Yarmouth/Gorleston, regarding jurisdiction over the Yare and associated harbourage. The latter produced several royal charters attempting, with little success, to bring matters to a satisfactory compromise; the general tenor was to confirm Great Yarmouth's jurisdiction over the haven, allowing the men of Little Yarmouth that victuals or goods not subject to customs could still be landed on their side of the river, but forbidding them to try to entice other cargos there.

| Buildings and fortifications |

Yarmouth is famous for its "Rows", a series of passages – too narrow to be called streets – separating the medieval tenements. By the end of the Middle Ages there were some 150 of them. The close packing of buildings, with narrow alleyways separating properties, is not unknown in medieval towns, although the extent to which this was applied in Yarmouth is unusual and may have been due to the confined area of solid ground for building on, or (in the cases of those on the western side of town) to the extension or addition of property plots in the direction of the receding riverfront. Many of Yarmouth's passages survived into the twentieth century only to be destroyed (with a few exceptions) during the Second World War. This layout of the land-holdings of the townsmen is evidenced as early as 1198, and continued in use into the thirteenth; most Rows were named after some prominent family residing there. During that period the population of Yarmouth expanded considerably; we hear from chroniclers that 2,000 inhabitants died during floods in 1286, and 7,000 died in the Black Death (thanks partly to the crowded Rows), although these figures must be taken with a pinch of salt – the town's population in the early fourteenth century was more likely around 5,000. The Rows all ran east-west (i.e. between the river and the shore), while the few main streets of the town ran north-south, reflecting the gradual spread of population southwards from its original focus. Apart from routes by the waterfronts, there were three main streets cross-cutting the Rows: Northgate, Middlegate and Southgate. It is debateable whether this grid pattern warrants Yarmouth being considered a "planned town". Also doubtful, yet not inconceivable (given Yarmouth's orientation towards the North Sea and the use of the Norse "gate" in major street names), is whether the Rows owe anything to the influence of settlers from Scandinavia, where similar types of street layout can be found.

During the fourteenth century, Yarmouth's government was faced with two major construction challenges which were very expensive: the provision of stable harbour facilities, and the building of town defences.

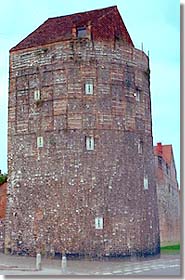

Yarmouth is one of the English towns where a relatively large percentage of the medieval town walls is still standing. These walls were built over a long period, the greater part of the work taking place between the 1330s and 1390s. The main threat must have been attack from the sea, and so the aim was to enclose the town on its coastal side and its two flanks, leaving the Yare channel to be an obstacle to any attack from landside. At the southern end of town, a boom was strung across the river to prevent outflanking by any attackers' ships. In addition to protection, the gates piercing the wall may have helped channel commerce and facilitate the collection of tolls, Yarmouth being one of the country's principal customs control points.

Yarmouth's medieval defences

Two towers from the southern stretch of the borough's walls.

photos © S. Alsford

Royal licence to enclose the town with wall, and to collect special tolls under the title of murage, was first acquired in 1261 (in the context of the de Montfort rebellion). The following year saw complaints from non-local merchants that murage was being collected from them, but they saw no evidence that any wall-building was going on; the king consequently seized the money collected. In 1279 he audited the town's murage accounts, after receiving complaints of corruption. It seems that construction work had still not begun; in fact, no work is known to have been undertaken before 1285. Nonetheless, the king recognized the importance of Yarmouth as a coastal defence and authorized murage on several occasions during the fourteenth century. However, particularly in those periods of greatest threat of invasion, which spurred renewed efforts on the defences, income could not keep pace with expenditure, despite occasional bequests from townsmen towards the work. In the face of a renewed French offensive, all townsmen were, in 1369, ordered by the king to contribute to the costs of strengthening the defences. By 1385/86, construction was still incomplete, and some of the walls that had been built were by now falling into disrepair; again the threat of invasion prompted the king to order everyone owning property in the town to contribute to costs. In 1457 the king allowed Yarmouth to apply to the work £20 of the fee farm due him.

Maintenance and periodic relocation of the haven must have been a similarly daunting task, but one even more crucial to Yarmouth since the commerce on which the borough economy (including local government revenues) depended was in turn dependent on a safe harbour. Silting had necessitated a new harbour entrance to be cut in 1346. By 1378, silting had resulted in the water no longer being deep enough to admit ships into the harbour. Despite a partial refocus of its attentions on the harbour at Kirkley Road, in the 1390s Yarmouth built a new haven, financed partly through a special levy of a shilling per last of herring. But by 1409 this too was in trouble and the king gave permission for £100 to be taken each year for 5 years from import/export customs, to finance yet another new haven. This one lasted for the remainder of the medieval period, although costly to maintain (again prompting the king to release the town, for several years, from part of its fee farm).

| Economy |

Like several other East Anglian towns, Yarmouth's location gave it advantageous access to the Low Countries and the Baltic, as well as to the river system leading into the English interior. Its economy was relatively specialized, it being the country's principal centre for the herring fishery (while archaeology has also revealed large quantities of oysters, although perhaps mainly for local consumption); the seasonal fishery stimulated related industries, such as the curing of herring, extraction of salt (for preserving herring) from brine and boat-building – an industry which also provided vessels for other mercantile activities.

As the fourteenth century progressed, Yarmouth's dominance in the herring was threatened by declining markets and competition from the Low Countries. Yarmouth did all it could to monopolize the trade in herring, largely through provisions for hosting. One of the forms this took was that visiting merchants were assigned to townsmen, who supplied accommodations and business assistance in return for a quarter of the hosted merchant's merchandize. Another form was for a townsman to equip and supply a fishing-boat during a season, in return for the right to purchase the entire catch of that boat. Yarmouth's leading merchant families dominated the hosting system; they also acted contrary to fair market practice by buying herring catches while still at sea and by threats of violence to encourage fishermen to sell their catches or to discourage foreign merchants from buying herring. The king's Statute of Herring (1357) – targeted particularly at Yarmouth, after complaints were voiced in parliament – attempted to combat such monopolistic features, as well as to limit the commission hosts demanded for selling the herring of hosted merchants and to limit the amount of profit from re-sale of herring by merchant middlement. But it proved difficult to enforce the provisions, there being no will locally to do so. Ordinances drawn up by the Yarmouth administration aimed at reinforcing the dominance of local men. Those of 1300 restricted the rights of outsiders with fish to sell, while defining the rights of hosts and the rights of all townsmen to demand a share of cargoes. Those of 1413 created wardens to supervise the herring trade and required fishermen to sell a portion of their catches (regardless of any arrangements with hosts), through these wardens, to townsmen.

In part because of its fishery, but also because it was a key defensive post on the east coast, Yarmouth was also an important maritime base. Many townsmen were ship-owners, and during the first half of the fourteenth century the town was the largest provider of ships north of the Thames for the navy during the wars with Scotland and France; for the siege of Calais in 1346, for example, it supplied 43 ships – compared to 25 from London, 19 from Lynn, 12 from Ipswich, and 25 of the king's own ships. At different times, three townsmen were even appointed to the rank of admiral of the northern fleet (notably John Perbroun, who commanded the northern fleet at the victory of Sluys).

Contributing ships was an unpopular obligation and was resisted. It of course exposed townsmen to the risks of damage or loss of their ships during war – for which the king rarely provided compensation. Equally important, the often long periods of "arrest" of ships, in preparation for their being called into action, deprived townsmen of the transportation needed to pursue their livelihoods. Furthermore, the town was occasionally required to provide supplies for expeditionary forces, and the king was not prompt in paying for these. By the middle of the fourteenth century, Yarmouth was seeking fee farm relief on the grounds that it had lost more than half of the fleet of some 90 ships that served it in the 1330s, while the war had made fishing boats one of the targets for attack and had generally disrupted maritime trade. Repeated complaints brought the town some tax relief. Yarmouth's loss of a maritime defensive capability, together with the failure of the townsmen to invest in rebuilding their fleet, is one reason why the king put more emphasis in the second half of the century on completing Yarmouth's walls.

A large fleet whose sailors were experienced in naval warfare doubtless contributed in encouraging Yarmouth ships to resort to piracy. Such acts were sometimes directed against the ships of England's enemies, but might equally well be against ships of its allies, or even English ships. An investigation of 1340 accused 34 Yarmouth ships of piratic activities. Yarmouth's ships were similarly the target for piratic attacks. The fleet also came in useful for raiding the Cinque Ports.

Yarmouth's geographical advantages resulted in it surpassing in wealth the larger and longer-established Norwich by mid-fourteenth century; of provincial towns, it had the fifth highest assessment in the national tax of 1334. But it suffered from the general economic recession later in the century, from the continual problems with the silting of its harbour, from the draining effects of the constant competition with rivals for control of trade, and from losses to its merchant fleet from war, piracy and shipwreck. In the second half of the fourteenth century, the herring trade was in decline, perhaps initially as depopulation caused by the Black Death reduced demand, but later because the coastal supply of herring was itself dwindling – fifteenth century fishing took place further out to sea – and was subject to greater competition from the fishermen of northern France and the Low Countries. This was offset a little by rising prices – by the close of the century herring was no longer the cheap dietary staple it had been at the beginning.

In the latter half of the fourteenth century, Yarmouth became a rival to Norwich for the status of staple town controlling the wool export trade. As early as 1319, Yarmouth was trying to persuade the king to appoint it a staple town. When Norwich was so appointed in 1353, Yarmouth expressed its resentment by stopping vessels from proceeding up-river to the city. In 1369, however, Yarmouth was chosen over Norwich as the staple, and in the 1390s the role fluctuated between the two towns. Nonetheless, wool exports never became a very significant part of Yarmouth's trade, nor was the trade in wine particularly important to the local economy. Local merchants appear to have relied on smuggling to increase their profits, which was not too difficult when they themselves were the holders of the various royal posts associated with customs collection or policing of smuggling. As the wool trade diminished, Yarmouth followed the regional trend of turning to the export of cloth, and this trade was of some importance to the town into the early sixteenth century.

| 1 | I am grateful to Dr. Anthony Durham for letting me see a draft of a paper in which he argues for Germanic origins of Saxon Shore fort names. |

| Information sources |

The following is a small selection of published sources of information about medieval Yarmouth. For additional secondary sources as well as primary sources, see the bibliography to The Men Behind the Masque.

Ecclestone, J.P., and J.L. Ecclestone. The Rise of Great Yarmouth: the Story of a Sandbank. Norwich, 1959.

Palmer, Charles John, ed. The History of Great Yarmouth by Henry Manship, Town Clerk, temp. Queen Elizabeth. Great Yarmouth, 1854.

Palmer, Charles John. The History of Great Yarmouth, Designed as a Continuation of Manship's History of that Town. Great Yarmouth, 1856.

Palmer, Charles John. The Perlustration of Great Yarmouth, with Gorleston and South-town. 3 vols. Great Yarmouth, 1872-75.

Rutledge, Elizabeth and Paul Rutledge. "King's Lynn and Great Yarmouth, two thirteenth-century surveys." Norfolk Archaeology, vol.37 (1978), 92-114.

Saul, A. "Great Yarmouth and the Hundred Years War in the fourteenth century." Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, vol.52 (1979), 705-15.

Saul, A. "Local Politics and the Good Parliament." Pp.156-71 in Property and Politics: Essays in Later Medieval English History, ed. T. Pollard. Gloucester, 1984.

main menu |

appendix 1 |

| Created: August 29, 1998. Last update: October 26, 2016 | © Stephen Alsford, 1998-2016 |