History of

medieval Norwich

History of

medieval Norwich History of

medieval Norwich

History of

medieval Norwich

| Power struggles with rivals |

By the close of the thirteenth century, Norwich was one of the major cities of the realm. The defended boundaries it had chosen to define encompassed an area larger than London. Its population, probably numbering between 20,000 and 30,000, was served by about 60 parish churches, and five bridges crossed its river (more than any other medieval English town), in part an indication of the intensive occupation along the river shores, particularly by craftsmen engaging in leather working and cloth finishing industries, who needed access to water, and increasingly by merchants' warehouses and homes. Wealth brought pride, and pride felt the need for power. Local government had moved beyond amateur status to encompass an executive of bailiffs, the beginnings of a formal town council, and specialized officials such as treasurer, coroners, and town clerk. But in order to consolidate the growing control over its own administration, the city had to face challenges from a variety of rivals in the areas of legal jurisdiction and economic matters.

| See Map of Norwich ca.1260 (60K) |

To a community becoming increasingly conscious of its social and political "personality", it was intolerable that its physical personality be so vaguely defined. The first step in remedying this was to delineate the city limits. At some time during Stephen's reign the boundary of Westwyk was indicated by a ditch, and that of southern Conesford by a gate on Berstrete and a few decades later by another gate on Southgate; the latter may have been a response to territorial claims of Carrow Abbey, founded south of the town in 1146. In 1235 the city was fined for attempting to assert its jurisdiction in common fields outside the hundredal limits of Norwich. Although we don't know where those fields were exactly, they may have been in the southwestern quadrant of the city that the citizens made a point of taking in, when the king gave them licence to enclose the city, in 1253, with a ditch and nine gates. This ditch swept in a wide arc, connecting Westwyk and southern Conesford and advancing into Taverham hundred in the north. It represented a territorial claim, and one that was challenged both by country-dwellers (who complained that their old paths had been blocked) and by the cathedral priory, which accused the city of illegally enclosing lands belonging to itself, Carrow Abbey, and rural hundreds.

Undaunted, the citizens consolidated this coup by building a stone wall

along the same boundary; it was mainly constructed from flint and

mortar, dressed with limestone. The importance of boundaries, in terms of

control over territories and commerce, is seen in that wall-building was

an expensive and long-term undertaking. To finance it, the city obtained

royal grants of murage in 1297,

1305, 1317, and 1337. On the last occasion they

farmed the murage to citizen

Richard Spynk,

who also contributed out of his own wealth to ensure the

completion

of the walls – in return for generous concessions

by the city. Although there was provision for artillery and portcullises,

it would be a mistake to think of these walls as exclusively defensive in

purpose. The length of their line, the poor quality of construction,

and the disinclination of the citizens to keep it in repair, together with

the fact that the eastern boundary had no wall (only the river as a

barrier), meant that they would not be a real obstacle to any serious

attacker. As part of Spynk's contract with the city, the latter was

required to take steps to prevent abuse of the walls, such as by

citizens hanging cloths to dry on them. By the 1370s, however, the city

itself was leasing out the defensive towers for commercial uses, such as

milling. Despite this, the walls were an expression of city pride and

independence, intended to channel trade into and out of the city at set

points where tolls could be collected (which explains the anger of the

country people in 1253, no longer able to evade those payments).

Norwich fortifications

[left] The southernmost element of the wall, watching down from the

top of Carrow Hill,

was this large tower, which came (in the 15th century) to be called

the Black Tower.

[centre] A western stretch of wall and tower just south of

St. Stephen's Gate

[right] On the bank of the Wensum, where it looped southwards

around the meadow

of the Great Hospital, the Prior had

a tower, perhaps related to collecting tolls on

river-bound traffic, but also used as a prison. In 1378 this was turned

over to the city.

Rebuilt in brick and flint in 1398/99 as an

artillery tower,

with a palisade connecting

it to the fortified Bishop's Bridge further south, its present name

"Cow Tower" was

acquired from association with the cows pastured in adjacent

Cowholme meadow.

photos © S. Alsford

The monks' complaint in 1253 was prompted by other reasons. It was part of an ongoing defense against the encroachments of the citizens. From early in the century there had been a number of points of contention between city and cathedral-priory. Not all of the lands given to the cathedral priory were enclosed by the cathedral precinct wall; the Prior's Fee included a number of areas within the city, whose residents (based on royal grants to the Prior) refused to contribute to taxes imposed on the city or to acknowledge any authority of city officers over them. The city tried to claim jurisdiction over the inhabitants of those areas, countering the monks' accusations with those of its own. In 1244 one issue was settled when it was agreed the Prior's tenants would contribute £20 towards the fee farm (£100 at this time). In 1249-50 the city complained that the Prior was taking "holy-day" tolls on bakers and other citizens, but the Prior successfully defended that this was a customary right. In 1256/57 the Priory's baker was killed in a quarrel with a citizen and, since he had died on the Priory grounds, the city bailiffs were denied permission to hold the inquest. The same year saw a conflict over the Prior collecting landgable, while the following year saw the bailiffs assaulted by a party of monks and their servants in a jurisdictional dispute over a piece of property.

All this came to a head in the summer of 1272 when the citizens erected a quintain (a target for lance practice) on Tombland, in a location probably chosen to annoy the monks. A quarrel broke out with servants of the Priory, who were forced to retreat, but one of the servants shot a citizen with a crossbow. After an inquest, the city coroners arrested two priory servants, following which the Prior excommunicated and interdicted the citizens. By August things had reached a state of siege, with the Priory gates closed and its servants taking potshots at citizens from behind the walls. An attempt to negotiate a peaceful settlement when the Prior refused to endorse an agreement. Instead he brought in three barges full of armed men from Yarmouth, which had its own reasons for enmity with Norwich. These and the Priory servants sallied forth into the city at night: killing one man, wounding others, robbing, looting and burning. Despatching a complaint to the king, the city authorities called for a muster of citizens in the marketplace the following morning (August 8th or 9th). An attack was then made on the Priory; one of its gates was burned down to effect an entry into the precinct and a church immediately within was looted and burned. The fire spread to other buildings, even to the cathedral (although the damage was much exaggerated in the subsequent legal proceedings); 13 defenders were killed – some in formal execution style – while others were taken off to prison, and the attack disintegrated into general plundering of cathedral treasures. It was not a total rout, however, for the following day the Prior, William de Brunham, himself killed one of his opponents.

Within a week the king was taking action, despatching commissions

to bring matters under control and ordering the sheriff and

the constable of the castle to assist the commissioners.

In September, (although in declining health) he set out for

the city in person to supervise the investigation; arriving on September

14, he subsequently placed both city and Priory under wardens. The

accused included citizens who had played leading roles in local

government. Following the trial at least 29 were hanged. A further

investigation in December reached the conclusions that the fault in

the affair lay with the Prior's violence against the city, and that

the fire in the church had been an accident of smiths employed by the

Priory; Brunham was arrested and turned over to his bishop to be tried

(but his punishment was light). In 1275 the affair was finally settled

through arbitration by the king, who set damages payable by city to

Priory at £2000, in return for which the excommunication was

lifted from the city. Arguments between the two sides continued,

however, and – although the Prior's Fee would remain a thorn

in the side of city authorities until the sixteenth century –

the king urged them to a compromise (1306), which conceded the city

much of the jurisdiction it wanted.

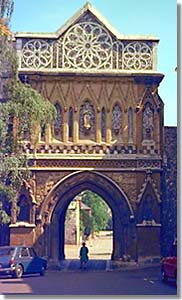

Ethelbert Gate

Ethelbert Gate

One of the two principal gates leading from Tombland into the cathedral

close (the other built ca.1420 by Sir Thomas

Erpingham), the

Ethelbert Gate

was built in the early 14th century at the cost of the citizens

as part of a settlement with the cathedral, and particularly

in recompense for the burning down of St. Ethelbert's church

during the 1272 riot. Its carving of knight versus dragon may

be an allegory on the event.

photos © S. Alsford

Encouraged by this success, the citizens immediately turned their attention to the waste-land in the borough, which belonged to the king. This land had developmental potential which represented annual rents for the city treasury. In 1307 Norwich petitioned the king for a grant of all the waste-land ... and was refused. So the citizens did what was commonly done in other boroughs and built on the land anyway, accumulating rents adding up to £9.11s.8d annually by 1329, when the royal escheator demanded these rents be handed over to the king. An appeal to the king, however, produced a decision in the citizens' favour, conceding them the waste-land.

Their next target was the Castle Fee, an area encompassing not only the castle but an expanse of surrounding land housing many persons, under castle rather than city jurisdiction. The citizens resented this exempt jurisdiction in the midst for much the same reasons as they did that of the Prior's Fee: the lay inhabitants might profit from city liberties without being liable to the obligations of citizenship, and they might commit crimes in the city and then seek sanctuary of the Fee, where they could obtain trial from a favourably-disposed jury of their fellows. There was also the potential physical threat, exemplified during the barons' wars: in 1264 men from the castle threatened the city coroners so that they could not complete inquests, and burned down the house of a citizen.

In 1344, the citizens took advantage of the king's presence in Norwich to plead their case. Investigation revealed to Edward that the castle, whose defensive fortifications had by now had fallen into disrepair, was of no military value and that a grant of the Fee would mean only a very minor loss in revenue, since most revenues would continue to come to him through an (inevitable) increase in the city's fee farm. So in 1345, he transferred to the city all but castle, shirehouse (the seat of the county court), and their immediate enclosure. This area was not integrated with adjoining leets, but maintained an independent one, with city bailiffs replacing the sheriff in its court.

A similar series of rivalries is seen in economic affairs, as the city sought to monopolize trade and control the conditions under which it took place. The first step in the process was to obtain the right to exact tolls on merchandize passing through the city gates, as well as freedom for the citizens from paying such tolls in other boroughs. The latter was one of the grants in the 1194 charter. The former was not explicitly granted but was probably implicit in that charter's grant to Norwich of all customs valid in London. In 1305 the citizens obtained a more specific list of tolls from which they were exempt.

Naturally, the right to take tolls and the exemption from tolls elsewhere – which the king granted to many towns – worked against each other. Merchants from other towns coming to Norwich might claim to be exempt from Norwich's tolls, while Norwich merchants might face demands from towns they visited that they pay tolls there. The 1194 charter therefore granted that, should toll be illegally taken from a Norwich citizen and the offending town refuse to compensate, Norwich's reeve could exact the amount due from the goods of any merchant of the offending town found in Norwich. Again, since this was a common grant to towns, it only exacerbated the situation, leading to arguments, reprisals, and counter-reprisals. A further round of royal grants (in Norwich's case, in 1255) specified that no citizen's goods should be seized elsewhere in relation to any debt for which they were not the debtor or guarantor, except in the case where the citizen was a member of a community which has refused to give satisfaction to the legitimate claims of a creditor. This was in tune with the medieval concept of every burgess sharing in the rights and obligations of his peers. But it did not help merchants whose goods might be seized through no fault of their own. Sometimes it was probably easier to avoid arguments with the officials of other towns, and just pay the tolls demanded. But then the capitulating merchant might be fined by his own leet court, for setting a precedent prejudicial to the chartered liberties of the city. The consequence of all this was to foster feelings of hostility between towns; particularly if foreign towns were involved, there could be political repercussions not to the liking of the king. Eventually the king banned the reprisal mechanism.

Norwich's concern to regulate local trade is clearly seen in its custumal (the collection of local laws). Many of the customs were devoted to rules of fair trade: equal opportunity trading for every citizen; no trading privately outside the market, nor before the ringing of the cathedral bell for the mass of the Virgin; no citizen was to assist a non-citizen avoid paying toll (for example, by pretending the latter's merchandize was his own); payment on the spot for goods bought from country-dwellers. The bailiffs duties included regular examination of the weights and measures of taverners, brewers, and other merchants, to ensure their accuracy; none was valid unless stamped with city seals intended for that purpose.

Once the problems associated with administrative jurisdiction were settled (by 1346) and after recovery from the effects of the Black Death (with property values rising again), efforts towards strengthening control over trade were redoubled. A special tax was levied in 1378 to buy up shops and market stalls, and it was then ruled that meat and fish could be sold only from these stalls. Similarly, two quays were acquired in 1379 and designated as the only legitimate places for loading and unloading goods; incoming goods of visiting merchants had to be stored in a community-owned warehouse while in the city. A new list of tolls was drawn up. In 1384 a large building just north of the market-place was acquired; part was converted into a Common Inn, where visiting merchants had to lodge, another part into the Worsted Seld, the only place from which country weavers could sell their worsted cloth to the citizens. Norwich's wealth in the late Middle Ages was founded primarily upon the cloth industry, especially manufacture of worsteds, a fine cloth sold throughout England and exported to the continent. When an inventory of city property was made, in 1397, it was quite extensive.

Part of the effort in controlling trade was directed at reorganizing the craft gilds. As rivals for control of trade conditions, craft gilds were at first suppressed by Norwich authorities. Besides fixing wages, prices and standards of manufacture, the gilds also deprived city courts of revenues from fines, by settling quarrels between members through internal arbitration. The 1256 royal charter included a clause outlawing gilds, and tanners, fullers, saddlers and cobblers were fined by the leet courts in the 1280s and '90s for having gilds. But by the second half of the fourteenth century it had become clear that suppression was ineffective; it gave way to a policy of recognition combined with supervision. An addition to the custumal authorized the bailiffs and city council to appoint annually a few members of each craft to act as wardens and check, several times a year, on the conduct of the city craftsmen; any fraudulent practices or defective work were to be reported to city authorities to act on. In the first half of the fifteenth century further steps were taken to control the gilds, climaxing in a lengthy set of ordinances (1449) by which gilds were to be governed.

In the area of trade, there were other rivals over which the city had less control. One source of dispute between monks and citizens was the fair rights on Tombland. The 1306 compromise mentioned above conceded the citizens first choice of which part of Tombland they would use for their stalls. The citizens also resented the Prior's right to hold a piepowder court (a speedy dispute-resolution process for travelling merchants) during the fair; in 1380 city authorities jealously ruled that any citizen taking a case to the Prior's court would be deprived of citizenship. Norwich petitioned to have its own piepowder court in 1443; although this was granted a few years later, there is no sign they ever went ahead and held one.

The Merchants of the Staple represented another independent jurisdiction, via the law-merchant. Norwich was one of a handful of staple towns (exclusive ports for the export of wool) during the reigns of Edward II and Edward III. In 1353 a royal statute set up organizations in those towns, each headed by a Mayor of the Staple, whose court had sole jurisdiction over foreign merchants and cases of debt, trespass, or breach of contract involving their members. However, since Norwich's staple organization was dominated by its own merchants, there was probably no serious conflict here.

Norwich's role as a staple was one factor in a long-standing rivalry with Great Yarmouth, which was made staple town in 1369 in place of Norwich. However, the hostility really went back to the question of which town was the port having right to exact tolls on boats using the Wensum. As early as 1257 Norwich complained that Yarmouth was stopping ships from coming upriver and forcing the merchandize on board those ships to be sold in its own market. This would mean a loss of some of the revenues Norwich needed to pay its fee farm. An argument of that nature was always guaranteed to be persuasive to the king. Renewed complaints in 1333 prompted a royal mandate to Yarmouth bailiffs to desist. By this time Yarmouth appears to have captured enough of the disputed commerce to have become wealthier than Norwich.

Rivalries such as those described above played their part in the historical process which brought Norwich to the point of incorporation. The conflicts revealed to city authorities the need to strengthen their powers, and incorporation represented the highest expression of privileges that might be attained by local government of that time. A burning sense of identity and local pride is revealed by these conflicts, as well as by general distrust of any outsider (the difference in breadth of outlook between those times and ours being illustrated by the fact that to the medieval townsmen a "foreigner" was anyone living outside the borough, while someone from parts we today would classify as foreign was termed an "alien").

The impulses towards incorporation, from the borough's point of view, were a tangled web of circumstances reacting upon themselves. Gaining control of the fee farm may have brought a degree of political independence, but it did not profit the borough financially. Decreasing revenue from tolls, as the result of royal grants of exemption, and from rents (which remained at a fixed level), in the face of mounting costs as the size of bureaucracy grew, public properties needed maintenance, and city walls were built – on top of annual payment of the fee farm as well as frequent royal taxes, made things difficult financially for the city. Traditional revenues became inadequate to meet the fee farm, and so that had to be given first call on new revenues. In 1305 the king gave the bailiffs the power to levy local taxes. It became clear that property-holding was the likeliest cure for the city's economic ills; yet the lack of a formal existence in the eyes of the law was a hindrance to this. The 1404 charter remedied that.

A reflection of the improvement of city fortunes and the crystallization of the spirit of community is seen in the development of record-keeping. Norwich's first century of independence saw the appearance only of "records of necessity": court proceedings, financial accounts, and registration of deeds to property. In the decades following the completion of the walls and acquisition of the Castle Fee we see the commencement of a Book of Memoranda (memorabilia concerning the city, later used for enrolling the names of new citizens), the drawing up of a new version of the custumal, the recording of proceedings of the city council, and the inventorying of city property. All this reflects growing self-confidence and maturity.

In many ways, the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries were the heyday of medieval Norwich (and other boroughs). We see signs of a deep satisfaction with living in urban communities, and expressions of civic patriotism and a sense of all-for-one and one-for-all. Yet, as the fourteenth century wore on, the idea of the common good was losing its hold and, partly as a result of the trend towards incorporation (which, from the king's point of view, was an attempt to impose a certain uniformity on his boroughs), new forces of self- and class interest came to the fore to undermine the notion of community in the borough.

previous |

main menu |

next |

| Created: August 29, 1998. Last update: November 2, 2014 | © Stephen Alsford, 1998-2014 |