a. Enfield

Enfield is today the northernmost borough of London, although in the Middle Ages was in process of developing into a small market town in Middlesex, with perhaps a few hundred scattered inhabitants at the time of Domesday, but none of them burgesses, for Enfield did not acquire borough status until after the medieval period. In 1303 the manorial lord of Enfield, husband to a daughter of Edward I, obtained royal licence for a Monday market – which might suggest pre-licence market activity taking place Sundays in or beside the churchyard – and two three-day fairs, though nothing further is heard of the market until the next century. Where these events were held is uncertain, but probably on a larger version of the present marketplace, then the village green – earlier a field that likely gave Enfield its name – between the parish church of St. Andrew (in existence by the thirteenth century, though its present fabric is a little later) to the north and the manor house on the south side; for a while the village was known as Enfield Green. That one of the fairs took place around St. Andrew's day suggests its site was close to the church. A boundary ditch on one side of the marketplace, discovered during excavations in the early 2000s, had been infilled in the early fourteenth century, as a prelude either to expansion of the village or construction of a more imposing manor-house. By 1364 we hear of houses built along the other sides of the green and encroachment continued into the centre of the site. The marketplace regained space, to its present size, in the seventeenth century, by which time butchers were prominent among the stall-holders; in 1648 we hear of 21 stalls and 90 trestles for the use of those trading in the market.

(above) Enfield's marketplace on a non-market day, allowing

an almost unobstructed view of the space allocated for the market. St. Andrew's church

can be seen beyond the trees at rear.

(below) The marketplace on market day.

Photos © S. Alsford

Certainly this green, situated on a secondary road crossing north-south routes around which early settlement gathered, became the focus of the small town after a Saturday market was established there in 1632, some years subsequent to a royal grant of a market charter (1618) and the acquisition and demolition of an encroaching building. By 1670 the new market was furnished with a market house, market cross, weigh-house, pillory, and a line of shops along one side; it then accommodated 24 butchers' stalls.

The market house in Enfield markeplace, with stalls

in place. This structure is a successor to that erected in 1632, which was

demolished some years after the market entered a period of inoperation,

to revive, as did Enfield's fortunes generally, with the advent of

the railway.

Photo © S. Alsford

Today the number of stalls is not so very much greater, though the range of goods traded rather wider and (understandably) excluding exposed meat. The church still stands at its rear, a tavern (rebuilt 1899) is in one corner of the marketplace and, diagonally opposite, what was built as a bank, superseding an inn; in the centre rises a market house erected, along traditional lines, in 1904, replacing a stone market cross which had itself superseded the earlier market house of 1632. On the other side of the road is Enfield's main row of shops, stretching out from a department store that replaced an Elizabethan palace which had itself succeeded the medieval manor house. The marketplace at Enfield remains a very well-defined and compact space, roughly square.

b. Cambridge

Cambridge developed out of a number of small nuclei of settlement most of which were located within a triangular area of land. This was bounded on one side by the River Cam, which connected to the Ouse and Nene, and was accessible to sea-going vessels into the thirteenth century, although the Nene passage was damaged by silting up; and on a second side by the line of a Roman road – an important land route between East Anglia and the Midlands – that made a diagonal approach to a crossing of the Cam, at the north end of the triangle. The crossing had been guarded by a Roman fort on the farther bank, where the Normans later erected a castle. A lesser ford lay at the south-western corner of the triangle.

The northern crossing, later known as Great Bridge, provided the name (by 875) for the place that developed into a town, through coalescence of the various village-like settlements. The Romans may have built the original bridge (or at least a fording causeway). If not, one would have been desirable as part of the posited conversions into burhs of: the area north of the river crossing by Mercia in the eighth century; an area on the south bank by Danish invaders; and the settlements still further south by Edward the Elder after his reconquest of Cambridge. Any of these burh projects could suggest the presence of a market of some importance within a region whose fertile lands would only be increased as fen reclamation gathered steam after the Conquest; though whether such a market lay north or south of the river crossing remains a matter for debate – possibly we are talking here of separate markets.

It is conceivable that the early focus of settlement in the Anglo-Saxon period – or at least the residence of the administrators and thegns – lay on the north side of the river, but this focus gradually shifted southwards, to that area better served by water and land routes for developing the commercial potential of the town [aspects of the debate are argued by Mary Lobel in the Cambridge fascicle of volume 2 (1975) of the Historic Towns series, and by Jeremy Haslam in "The development and topography of Saxon Cambridge," Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society, vol.72 (1984)]. The construction of the castle (1079) disrupted the northern area and obscured some of the evidence for modern investigators. However, the post-Conquest borough developed within the triangular area, through which ran one main road (today Trumpington Street) along which at fairly regular intervals had been built churches at the corners of intersections with lesser streets, serving the various settlements. By the time of Domesday, Cambridge had been divided into ten administrative wards (possibly a legacy of Danish rule), though whether they were located on both sides of the river, or all within the burh fortifications, is uncertain. They are suspected of having later helped shape the parishes.

Views down onto Cambridge's marketplace, from the tower of St. Mary the Great.

(above) A general view, with shops at rear in sixteenth and seventeenth century buildings,

and the Guildhall on the right-hand side of the marketplace.

(below) Part of

the marketplace, the fountain at lower right marking its centre.

Photos © S. Alsford

The marketplace was set at a central point along this main street, within a gravel terrace raised out of the marshy ground around the river; archaeology has confirmed that the most densely settled part of Cambridge in the Late Saxon period was that between the marketplace and St. Benet's church to its south, although the market ward – on Market Hill then as it still is today – was probably served by the church of St. Edward, on one side of the marketplace. Note that, despite its name, the marketplace is not on an elevated site; 'hill' here derives from a use of that term to refer to a public meeting place. Through the Late Middle Ages Cambridge retained its role as an important regional market centre, although competition from Lynn, through which most of Cambridge's international trade was channelled by mid-thirteenth century, and drains on borough jurisdiction and revenues by the university that appeared in the early thirteenth century and grew in size and influence at the expense of the burgess community, interfered with any prospects of it becoming a major player in international trade.

A market cross was erected at some point in the Late Middle Ages, but pulled down in 1786; the marketplace was paved in 1613 and the following year a fountain head was installed as part of the water-distribution system known as Hobson's Conduit, replacing some kind of earlier water-source, mentioned in 1429. At that period the area between the cross and fountain was for vendors of fruit, herbs, and vegetables, and the opposite side of the cross was allocated to sellers of milk; other areas were assigned to fishmongers, and to butchers (in front of the Guildhall, for Guildhall Street was earlier known as Butchery Row). Vendors of grain, butter and poultry were placed on the north side of the marketplace, and there was a separate row for cookshops, possibly along the eastern side. This differentiation was the case in the Middle Ages too, an ordinance of 1377 having specified the various locations; rows named after other particular trades are known from records, although their precise location is uncertain.

Civic administration seems always to have been based in buildings located beside the marketplace. The new Guildhall built in 1386-87 (probably adjoining and superseding a building called the Tolbooth, which thereafter may have been used as a gaol, in addition to continuing its medieval role in collecting market tolls and other revenues that had been put towards the city's fee farm) was designed as a two-storey structure with an arcaded ground floor open on three sides, to accommodate market stalls; court sessions were held and other administrative business dealt with on the upper floor. That butchers, fishmongers, and tanners were selling in the marketplace on a regular basis is indicated by a local ordinance prohibiting them from setting up stalls there on days other than the official market day (Saturday).

Photo © S. Alsford

Looking across the centre of Cambridge's marketplace, past

the fountain, towards St. Mary the Great. This photo reflects the dual character

of Cambridge, as on the one hand a town with economic functions and as the base

for an ecclesiastical centre of learning known as a university. Although the location

of St. Edward's makes it likely to have been the church originally associated with

the marketplace, today is it Great St. Mary's which overshadows the market. First

heard of in 1205, presentation to its living was passed from king to university in 1342

and it was often used by the university for congregations and other purposes, as well

as for meetings between university and borough leaders. The present structure dates

from late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Lack of space in the marketplace became increasingly apparent as the economy grew. In 1346 an attempt was made to prohibit traders from setting up stalls on ecclesiastical properties or on sidewalks. It was not until a fire in 1849 removed structures between the market and Great St. Mary's that there became possible the expansion of the marketplace from its original site, which covered the east and south sides of the current market square. The fountain now in the marketplace was a replacement in 1855 for that of Hobson's Conduit, which itself superseded some kind of public water source whose presence is evidenced in 1429.

Today Cambridge's central market is open daily, and there are over a hundred stall sites available for rental, divided into seven main rows, all surrounding the central fountain. Basic stall structures are supplied by the municipality, stall-holders having limited rights in making alterations to the stalls. The function of the stalls is restricted to trading, and trading is restricted to the boundaries of the stalls – no hawking (carrying about of goods for sale) is permitted in the marketplace.

c. Norwich

Tradition, topographical evidence, and archaeology all support the belief that Tombland was the site of market activity in the pre-Conquest town. The Norman colony introduced after the Conquest was provided with its own marketplace – first mentioned ca. 1096 (but not in Domesday) and implicit in the name Newport that became attached to the planted settlement. This gradually acquired pre-eminence, thanks in part to the immigration of French merchants and craftsmen with continental trading connections and to the proximity of the castle garrison, which would have been a source of business. But it was also also due to a shift away from the old centre of urban activity, as the building of the castle and cathedral displaced residential areas adjacent to the Saxon marketplace; this led to Tombland being transferred to the jurisdiction of the bishop and prior (who thereafter used it for a reduced market and an annual fair), with part of it possibly being absorbed into the cathedral-monastery precinct.

View from the castle parapet towards the marketplace, with the present-day City Hall at rear,

the medieval Guildhall at right and St. Peter's Mancroft church at left.

Photo © S. Alsford

The surrounds of the modern successor of the Mancroft market, developed over the course of the next century or two, still retain many of the landmarks that would have been seen by late medieval shoppers. To the east of the marketplace looms the castle keep atop its mound. To its south the cemetery and church of St. Peter's Mancroft, which was likely built in conjunction with the establishment of the marketplace and acquired prominence among the city churches as the market gained importance and attracted many of the leading merchants to live in the parish. On the north side the old Guildhall is the late medieval replacement for an earlier administrative building. The east and west sides (the former interposing between market and castle) were less lined with residential/commercial buildings than later became the case, but shops – some starting life as little more than sheds – were already beginning to ring the market stalls, and each side of the marketplace was serviced by at least one tavern. Today the western flank is taken up with the City Hall which in 1938 superseded the Guildhall as the base of civic administration. The marketplace sloped gently downwards, west to east, towards the Great Cockey, a north-south stream which had been groomed since before the Conquest into a water source for community needs, and which may have supplied water for market uses, although there was also a well in the marketplace.

The size of the area occupied by medieval Norwich's market reflected both the importance of the city and the size of its population, which had roughly tripled between about 1050 and 1300, as well as the wide range of industries established there, many of whose products were sold in the marketplace, alongside foodstuffs; it seems to have been the aim of city authorities to centralize all market activities in one large location, although this did not prove practicable and horses and pigs were sold in other locations, as were timber and dyes (chiefly woad and madder). Norwich's is still one of the largest open air markets in the United Kingdom.

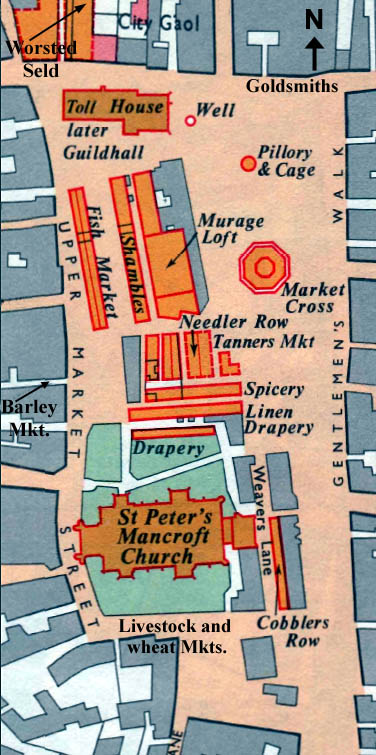

Plan of the marketplace ca. 1789, but showing major features in

the Late Middle Ages. Many of the buildings (shown in grey) represent post-medieval

encroachments or stalls that had transformed into permanent shops/residences.

Sampled ( and modified by me) from a city map produced for

Historic Towns: Norwich, London: Historic Towns Trust, 1975.

Although crowded and heterogeneous in its facilities, the Mancroft marketplace shows, behind its development over the course of several centuries, some signs of conscious organizational efforts to prevent it becoming a free-for-all, a process that must have been complicated by the fact that the marketplace was made up of separate lots of land, rented out by private owners and periodically changing hands. Despite this, it became possible to reserve specific areas of the market for particular types of commodities, creating logical groupings that must have made things easier both for shoppers and market supervision.

Within the central area we can discern a layout arranged in three main blocks, each comprising multiple rows of stalls. Leather goods and, increasingly, textiles were the leading manufactures of Norwich around the beginning of the fourteenth century; the finishing of 'white' cloth was the main thrust, but by the close of the century weaving was gaining ground. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries roughly a third of the immigrants who took up citizenship were cloth-workers. Traders in those products likewise consumed a large amount of marketplace space.

The central block was divided between leather-dressers and needlers, the latter one manifestation of another significant local industry: the manufacture of metal wares, especially smaller items. Tanners, mixed in with some shoemakers, occupied a good-sized area on the east side of these stalls, facing, on the eastern boundary of the marketplace – much later known as Gentlemen's Walk because of the fashionable shops that became established there – stalls or shops of hosiers (makers of leather leggings, who met stiff competition in the fourteenth century from tailors offering woollen hose), saddlers, and more shoemakers. While shoes were often custom-made for individual clients, the demand for this item of clothing was sufficiently strong that a few common sizes could be produced in volume in anticipation of sales. One of the streets connecting the marketplace to the castle bailey was known at different times as Saddlegate and Bridlesmith's Row, while the stretch of the market associated with hosiers ended at the corner of another such street, named Hosiergate. On the opposite (west) side of the block was located the bread market, with a myriad of small traders displaying basketfuls of their goods.

The block at the southern end of the main market area, north of St. Peter Mancroft, was allocated to stalls of cloth-dealers. These were grouped according to the type of cloth in which they traded: dealers in worsted (a regional product), linendrapers (who purchased unfinished linen from country weavers and then dyed it ready for sale), and drapers (who dealt in native woollen broadcloth, and some probably also in imported cloths). There may also have been some skinners stalls in the direction of the tanners' market. Two rows of stalls in the drapery were lost when the churchyard expanded in 1368/69 to accommodate graves of victims of plague and famine; some of those stalls may have been relocated to the west side of the churchyard, but the post-plague drop in population had left many stalls vacant. We hear of a Weaver's Lane on the east side of the church, but here seem to have been more shoemakers (strictly, cobblers) in the medieval period.

At this period, between the central and the southern blocks, as a kind of buffer zone, were positioned stalls of mercers and spicers. The open area just south of St. Peter Mancroft was used for sale of cattle, sheep, poultry, and wheat; barley, which produced a cheaper kind of bread, was sold in a spot just off the western side of the marketplace.

The northernmost block also evidences the metal-working industry, with a row for ironmongers on its east side; nearby, at the corner of Hosiergate, cutlers were located and, along the north-eastern edge of the marketplace, goldsmiths shops, while the hatters had a presence further west on that boundary, behind the Guildhall site. But the main thrust of the northern block was to accommodate fishmongers and butchers, doubtless grouped together (and away from the Cockey side of the marketplace) because of the stench and detritus that was part and parcel of their work.

The northwest corner, between the stalls and the Common Inn (just north of which stood the Worsted Seld), was designated the vegetable market, though most of it was consumed when the Guildhall was built. There, and in a large swathe of open space along the eastern side of the marketplace (known as Nether Row, or the Lower Market), were found petty traders, mostly from the countryside, selling produce and foodstuffs. Some presumably sold from the backs of their carts or brought with them boards and trestles to erect temporary stalls, while others must have laid their wares out on the ground or sold them from baskets; for which privilege they paid a small fee, lower than stallage.

View between two rows of stalls in Norwich market. The slope of the ground

is apparent.

Photo © S. Alsford

In the aftermath of the worst outbreaks of plague and their adverse economic effects – as part of a more general policy, pragmatic and successful, to revive the city's fortunes, protect its merchants from outside competition, exert more control over prices and standards related to the foodstuff trades, and facilitate collection of the tax revenues that trade generated – the city authorities, with proceeds from a special levy on residents, bought up market stalls from which meat, poultry, fish, and wool were sold. They then required that those commodities be sold only from these stalls, rented from the city, with leases no longer than three years, so that rents (which proved a source of steady income for many years) could be adjusted periodically.

The decades that followed saw the acquisition of land on the northern edge of the marketplace for facilities to host visiting traders and centralize the sale of worsted cloth by outsiders; and in 1411, as work on the Guildhall – England's largest civic government building outside London – was being completed, a new market cross was put up. A generation later work was begun on rebuilding St. Peter's church on a scale echoing that of the Guildhall on the other side of the marketplace; it was completed about 1455. These book-end monuments must have created an impression, on visiting traders, of the wealth and authority of the mercantile elite that dominated Norwich society.

The Tollhouse that preceded the Guildhall indicates, through its name, the initial purpose of that building erected at one end of the marketplace. Around 1300 the Murage Loft was built for collection of this newly-granted source of tolls; it seems to have taken the form of a superstructure erected over stalls assigned to sellers of wool, located in a spot between the rows assigned to ironmongers and needlers. As other governmental functions absorbed space in the Tollhouse – part of the motivation to build the larger Guildhall – the Murage Loft became the point for collection of city tolls generally. Stocks, pillory, and a 'cage' – all for punishing market offenders in a way that involved public humiliation – were located in the north-eastern corner of the marketplace, not far from the Tollhouse, seat of the court that would impose such punishments.

The rows of 'stalls' of Norwich's market today are so elaborate,

enclosed, and not readily moveable that they have become, essentially, shops.

The modern and medieval Guildhalls are seen at rear.

Photo © S. Alsford

The present market, with its parallel and evenly-spaced rows of contiguous and standardized stalls (roughly 190 in all), the outcome of redesigns over the course of the last century, presents a much more consistent appearance than its medieval counterpart would have. By the close of the Middle Ages the market must have appeared to onlookers as a congested jumble of stalls of widely varying sizes, stalls in the process of becoming shops, shops in the process of becoming houses, and transient vendors who had brought goods into the city by cart or packhorse, or simply in baskets on their backs.

Yet even the modern market echoes the transition that characterized most medieval urban marketplaces: what once were rows of simple stalls have become enclosed and secured booths constructed in units each housing four businesses – a small step away from being permanent shops – and whose roofing and awnings of uniform style (though varied colours), when viewed from above, give a sense that the market as a whole appears almost a single indoor facility.