History of

medieval Norwich

History of

medieval Norwich History of

medieval Norwich

History of

medieval Norwich

| Effects of the Conquest |

The first few decades following the Norman Conquest saw drastic changes in settlement patterns at Norwich, as three new features were imposed on the landscape: a castle, a cathedral, and a French quarter — the first two acting as highly visible monuments to the transfer of power, constantly reminding the inhabitants that they were now subjects of a new regime. It was important for the Normans to make such architectural statements in Norwich, for by 1065 it had become one of the most populous boroughs in the country, with 1,238 burgesses on the land jointly owned by the king and earl Gyrth Godwinson, 50 in the soke of archbishop Stigand, and 32 in that of Harold Godwinson (a former earl of East Anglia). Yet by 1086 not a few of the wealthiest townsmen (presumably of Anglo-Scandinavian lineage) had deserted the town or gone down in the world, likely one consequence of the initial Norman subjugation, retribution following the failed rebellion led by Earl Ralph in 1075, urban redevelopment initiatives, and burdensome taxes (or oppressive tax collection), and we also hear of 480 bordarii – persons living in modest circumstance – though whether this was a non-burgess class that had also existed in the Confessor's time, or was a group of former burgesses impoverished by adversities following the Conquest is uncertain. The total population of the borough in this period was likely in the range of 7,000 to 10,000 people.

| Construction of castle and cathedral |

Many burgesses were displaced when their houses were torn down (probably along with the postulated palace of the Saxon earl) to make room for the cathedral precinct and the castle and its fee, in a central location in the borough, formerly occupied by much of Saxon Conesford. Recent archaeological evidence has suggested that many if not most of the dwellings here housed poorer townspeople; and also that a couple of minor churches may also have been demolished. The castle was in existence by 1075 and may have been built within a year of William the Conqueror's victory over King Harold Godwinson – if, as seems likely, the "Guenta" where William FitzOsbern built a castle from which to take charge of the northern half of the kingdom (in the Conqueror's absence abroad) may be identified with Norwich. Its site chosen for height and for proximity to the crossroads and fords/bridges, the purpose of the castle was not so much to protect as to control the inhabitants of a town where the Conqueror's principal enemies (the Godwinsons) had held influence. An original wooden structure would have been replaced by the present stone keep, the largest then built in England, within a few decades – perhaps as early as 1095, although more likely in the early decades of the next century, following construction of a drawbridge spanning the ditch between its mound and the inner bailey.

Norwich castle keep

viewed from the far side of the (Mancroft) marketplace

still appears to impose authority over this part of the town

as it must have done eight hundred years ago.

photo © S. Alsford

Ironically, the castle became a centre of resistance to the Conqueror during the rebellion (1075) of Ralph de Guader, Earl of East Anglia and son-in-law of FitzOsbern. The earl may have been supported by the burgesses, for a larger garrison was stationed there by the king after the rebellion was put down, and Domesday reveals that 32 burgesses had fled the town, while others had been ruined by confiscations of their property. Perhaps as additional punishment of the borough, the yearly farm (a lease of the revenues due from tolls, court fines and other sources – see below) owed by the burgesses to king and earl was tripled from £30 to £90 (although the pre-1066 farm may have been antiquated, and farms were raised in most towns where castles were built). This sudden increase must have been a blow, at a time when the number of burgesses capable of contributing to the farm had decreased. Ninety-eight houses had been replaced by the castle, 201 were tenantless for other reasons, and only 665 burgesses contributed to the farm.

Further disruption occurred in 1096 when, the East Anglian episcopal see having been transferred to Norwich (a plan conceived earlier, but delayed by the rebellion), construction of a cathedral began; enough was completed by 1100/01 for the consecration to take place. Where the castle had been a case of disruption of existing settlement through imposition, the cathedral-priory was a matter of acquisition of land, piecemeal; yet it too led to the demolition of possibly entire streets of houses and of a couple of churches. The lands given by king and earl for the purpose covered much of the old borough centre in northern Conesford; they stretched eastwards from Tombland (intruding into that space) to the marshy banks of the river. While we cannot be sure that it was a conscious plan to subjugate the Anglo-Saxon burgesses, the combined positioning of castle and cathedral served to cut off southern Conesford from the other sectors of the borough; and the two major Anglo-Saxon buildings – St. Michael's and the earl's palace – were pulled down. It may also be noted that most of the original Benedictine monks were Normans, while the castle garrison were Bretons.

The benefits to Norwich were that it was now an even more important centre for administration, both secular and ecclesiastical, than ever before; the cathedral brought to it "city" status. Cathedral and castle doubtless attracted more trade and industry to the borough, as well as providing buyers for the citizens' goods. The cathedral would have been a consumer of luxury goods, as well as an employer of both specialized and unspecialized labour during its lengthy construction period. However, Tombland – overshadowed by the cathedral precinct walls – began to lose its role as the focus of local trade. Wares were unloaded further upstream, on Westwyk and Coselanye banks, while the Prior began to claim fair rights on Tombland.

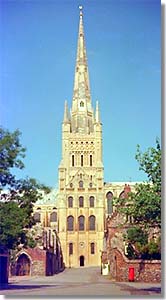

Norwich cathedral tower and spire

viewed from within the Close, looking northwards to

the south face. The cathedral took almost two hundred

years to complete; the unusually high spire was built at

the close of the Middle Ages to replace an earlier one.

photo © S. Alsford

| New settlers and their influence on Norwich |

An alternative marketplace had already presented itself, before 1086, in the French quarter established by Earl Ralph on the west side of the castle, just beyond the Great Cockey watercourse. This foundation was described as a "new town" in Domesday, and had a 6:1 ratio of French to English residents at its establishment, the number of Frenchmen in the novus burgus having risen slightly by 1086, though there were French settlers in other parts of Norwich too; although the earl took the initiative in founding this partner town, he was diplomatic enough to share lordship of it with the king on the same basis as lordship of the older part of Norwich. The new town plantation was part of a broader Norman policy of deliberate colonization of Anglo-Saxon centres (although the establishment of a separate but adjacent Norman quarter was itself uncommon). Yet we should not ignore the need to relocate some of the older residents displaced by the castle. The new town is later referred to as Newport, and still later as Man(nes)croft, which stuck. Historians have tried to interpret Mancroft in various ways. One suggestion was that it derived from magna croft, referring to the large size of the open area around which the settlers spread and on one side of which a parish church was built by the earl to serve their spiritual needs; another was that the name recalled a 'demesne croft' on which the lord planted his town, while a third suggested it a shortened form of "portmanscroft" (portman being an Anglo-Saxon term for burgess). More recently derivation from the Saxon gemaene croft, meaning communal field, has been proposed. These interpretations all share the understanding that the new settlement was planted on land not already settled – an impression only partly compromised by recent excavations, which revealed limited Late Saxon settlement and industrial activity in that vicinity – and, in essence, suburban, being outside the densely settled area and the burh enclosure; examples of Norman plantations of planned suburban settlements are known at some other English towns. The open area at the centre of Mancroft was doubtless, and probably intentionally, used for trading, and the large site of this marketplace suggests the earl's hope was to consolidate local commerce there, enticing it away from the Saxon markets at Tombland and on the Fishergate riverbank, while perhaps also taking advantage of artisanal activities established in Westwyk. It is significant that the original main access to the castle fee was on the Mancroft side – in the opposite direction to the old borough centre. Some of the land in Mancroft was held by Norman soldiers, while there is evidence of a number of houses in other parts of the town held custom-free by men associated with the castle-guard (e.g. crossbowmen, watchmen). By 1086, subsequent to Ralph's rebellion, the number of French burgesses had increased from 36 to 125, while the Anglo-Saxon population had decreased. Whether two streets, running westwards off the marketplace and parallel in their initial stretches, known as Upper Newport and Lower Newport, were part of the original foundation or later expansion is unclear, but the property plots on either side of them seem to have been a planned block of burgage tenements and at their western end, the streets converged at the location of another church.

Although we cannot dissociate the foundation, within a decade of the Conquest, with the building of the castle, Mancroft was more than an outer garrison for the castle. Part of its purpose was presumably a mechanism for provisioning the castle, and the type of settlers sought were merchants and tradesmen. Mancroft was made a borough in its own right, as its original name "Newport" indicates, with customary dues kept down to 1d. a head, to attract traders. It may well have had its own reeve and court. Its market, with a monopoly on castle business, gradually superseded Tombland and became the focus of the city. The Tolbooth established there to collect market dues would have been a preferable choice for the administration of justice to the open-air Tombland. When the rival Norman and Anglo-Saxon boroughs amalgamated into a single administration, we cannot say. Certainly we have the impression of a unified community when Norwich received its first royal charter of liberties in 1194, although there is some evidence that the new local administration (now to be chosen by the burgesses, rather than by the king) involved two or more reeves, with Normans and Anglo-Saxons sharing power.

However, by this time the cultural difference had dulled. Commercial intercourse, common ambitions (such as self-government), and common hatreds (such as against the Jews), helped forge Normans and Anglo-Scandinavians into one community. Despite Mancroft's rise and Conesford's decline, the character of the borough owed as much, if not more, to Anglo-Saxon than to Norman culture. A study of the customary laws of the borough shows little indisputable influence of French legal precedents. The burgesses resisted Norman innovations such as trial by combat or ordeal, or murdrum (a fine for an unsolved murder), obtaining exemptions from these in their first charter. The Anglo-Saxon preference for compurgation, as proof of guilt or innocence, persisted and only gradually gave way to trial by jury. That assizes of mort d'ancestor and novel disseisin were inoperative in towns was, however, a reflection more of the essentially mercantile interests of burgesses, rather than a cultural matter. And the abolition of the Anglo-Saxon miskenning (invalidation of a case in which pleading was not carried out according to strict formula) shows that the burgesses were not averse to discarding old custom when it hampered them.

On the other hand, there were some important consequences to Norwich from the Norman Conquest. The local authority of the sheriff (a king's man) was enhanced at the expense of the earl, particularly by making him constable of the castle. It was aversion to his government, in part, that motivated the burgesses to seek self-rule. More important was the stimulus the effects of the Conquest gave to trade, although these did were not fully realized until the twelfth century, and Anglo-Saxon and Norman had equal roles in this.

Nor must we ignore the less direct stimulus of the settlement of Jews in English boroughs, mainly from the time of William Rufus on (although an Isaac was living in Mancroft in 1086). Norwich was probably one of the earlier destinations of Jewish settlers – who came principally from northern France and the Rhineland – being a county town with a royal castle. A Jewish community there is evidenced in the mid-twelfth century chronicle of Thomas of Monmouth; the building of a synagogue in the reign of Henry II furthered the development of a Jewish quarter in Norwich. It was located at the castle entrance, on the route leading thence to the market. This placement gave it immediate access to the protection offered by the king (whose chattels the Jews were in law) and proximity to the place of business. Their principal business was money-lending, most others being closed to them. They had no role in city government, not being given citizenship (which involved the taking of Christian oaths), and this in turn disadvantaged them in commercial activities. Nor was membership in craft gilds open to them, again because of the religious aspects. On the other hand, Christian dictates made Jews the source of the necessary financial backing for commercial ventures; if they charged a high price for this service, it was because of the risks from unpaid debts and absorption of much of their profits by the king (in the form of heavy fines). The Abbey of St. Edmunds and the sheriff of Norfolk (William de Caineto) were among heavy debtors to Norwich Jews in time of Henry II.

Resentment at this state of indebtedness, combined with the burgess' instinctive antipathy towards any newcomer, fuelled by religious tension, resulted in aggression. The massacre of Jews in 1190, in Norwich as elsewhere, was in part "a new way to pay old debts", by getting rid of creditors. It was in fact at Norwich that the first accusation of ritual murder of a Christian by Jews was used as an excuse for hostility, and where a burgess community first meditated wholesale massacre of Jews (1144). Thanks largely to the protection of king, sheriff and castle, the Jewish community prospered in the face of adversity, such as:

St. Peter Mancroft

built by the earl to serve his new borough as

parish church; rebuilt on a magnificent scale

in the first half of the 15th century by the city's

merchants in gratitude for their prosperity. The

western tower, illuminated at night, illustrates

the imposing scale (note the castle in the background).

photo © S. Alsford

The growing prosperity of the city, as the leading market centre of one of the most populous areas of the country, is reflected in a number of things. The mint was still in operation. We hear of two minters by name, but there were certainly more in the city; the bishop himself was allowed to have one, and we hear of six in 1235, when the city's minting privilege was withdrawn. Hatred of the Jews for living off the needs of traders itself is a sign of flourishing commerce. Apart from beggars there is little indication of poverty, once the city had recovered from the adverse effects of the Conquest's aftermath; people seem to have had 3d. for masses, offerings or candles. Of course, the records tend not to pay much attention to the poor, nor are they as likely to leave much evidence in archaeological remains, although more recent excavations at Norwich have uncovered some dwellings of artisans and labourers. Houses of the wealthier citizens are more in evidence; they clustered particularly along the line of the river and around the marketplace. Reclamation of the marshy river banks was underway, and the population was expanding in the twelfth century in those areas as well as along streets in the southern end of town.

Another sign of the flourishing local economy is that over 130 trades and occupations can be identified in Norwich from records of the thirteenth century, and archaeology evidences considerable industrial diversity in the two centuries following the Conquest, such as copper working, bell casting, horn working, lime burning, and chalk mining. The leather industry was particularly important in Norwich in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, first with the skinners and later the tanners. On the other hand the pottery industry so prominent in the late Anglo-Saxon period had largely disappeared by the mid-twelfth century. On the rise instead, and to become centrally important in the long run, was the cloth trade and weaving – the latter associated with the Flemings, who settled in greater numbers in the Norwich region in the reigns of the Conqueror and his sons. Attempting to explain the capture by siege of Norwich in 1174, a French chronicler pointed out that many burgesses were weavers, not warriors. Like the Jews, Flemings were disliked by the other burgesses (particularly for trying to establish a monopolistic trade gild), despite the prosperity they brought to Norwich.

International trade continues to be evidenced with Scandinavia, Germany and the Low Countries. The extension of markets in Normandy and the lower Rhineland in the century following the Conquest was beneficial particularly to towns on the east coast. The Anarchy of the first half of the twelfth century left Norfolk relatively untouched, so that the century was one of general stability, conducive to commercial activity. The establishment of a shrine to St. William (the boy supposedly murdered by Jews) also helped attract more trade.

| The fee farm |

It was this prosperity that gave the citizens the resources to acquire a certain measure of administrative independence. In 1065 the king was the principal, but not the only, lord of Norwich. The private sokes of Stigand and Harold, however, gradually disappeared when cathedral, castle and Mancroft were raised on the sites of the sokes. The king still shared his lordship with the earl, who took the "third penny" of all dues until at least 1191; but that was probably his only surviving right in the borough, the sheriff having absorbed the earl's administrative duties. One of those chief duties was the collection of royal revenues from the boroughs. A popular method of doing this was to "farm" it: to negotiate a lump sum to be paid at the Exchequer in London. If revenues failed to meet the sum in any year, the sheriff had to make up the difference from his own purse. Naturally, he attempted the reverse: to collect more revenues than the negotiated sum, so that he could keep the surplus. Since large sums were often paid for shrieval office, we may guess that the profit was good, and there is evidence of various types of extortion. Often the sheriff made his profit by sub-leasing his farming rights to other individuals.

The burgesses were anxious to rid themselves of this drain on their income, by taking the farm into their own hands. Yet Norwich did not achieve this until 1194, although the burgesses were wealthy enough to have together afforded the money gift necessary to persuade the king to grant them the farm. Perhaps the Anglo-Saxon and Norman communities were still too much at odds to work in unison. More likely it was simply a case that Henry II, fearing that to give the boroughs too much power over their own affairs might lead to emulation of the continental communes, only experimented with grants of the farm to boroughs; his charter granted to Norwich circa 1158 went no further than recognizing unspecified local customs that the citizens claimed to be theirs by tradition. His sons Richard and John, on the other hand, had more pressing needs for money and were more amenable to selling to towns the privileges they wanted.

The burgesses paid 200 marks for taking the farm out of the hands of the sheriff (this in addition to the actual amount of the farm itself, which was £108). Historians have debated whether grant of fee farm automatically involved the right of the burgesses to elect their own officer to take responsibility for collecting the farm and accounting for it at the Exchequer. In Norwich's case, the 1194 charter clearly makes the association: after confirming to the citizens all their traditional liberties, in return for render to the king of the fee farm, by the hand of the prepositus (literally the "foremost" member of the community, usually translated as "reeve" or "bailiff"), the charter continues that the citizens may elect annually their own reeves (with the proviso that those elected be acceptable to the king). This represents the beginning of self-government in Norwich.

previous |

main menu |

next |

| Created: August 29, 1998. Last update: August 20, 2019 | © Stephen Alsford, 1998-2019 |