While England's cities and larger towns are not so difficult to distinguish from small towns, differentiating smaller towns from larger villages remains more problematic for today's historians [see, for example, summaries of conference papers in "Medieval Rural Settlement and Towns," Medieval Settlement Research Group Annual Report, no.8 (1993), pp.7-14]. Yardsticks such as plan form, population size, occupational and economic diversification (which, to an extent, tends to correlate to population size, except where the economy is dependent on some local industrial or occupational specialization, as at Thaxted), administrative institutions, or regulation of commerce do not suggest a huge distinction. Occupational structure within particular communities of known population size is rarely sufficiently well-documented during the medieval period to permit more than impressionistic conclusions, although the situation improves for the early post-medieval period [see, for instance, John Patten, "Village and Town: an Occupational Study", Agricultural History Review, vol.20 (1972), pp.1-16], but in conjunction with other evidence, such as the presence of a market or burgage tenure, can be indicative of a robust economy more characteristic of town than village. We should not be surprised at the difficulty in differentiating, and part of the problem is self-created and even obstructive: the analytical component of the human mind tries to understand the world around us, present and past, by segregating its manifestations into exclusive categories, often organized hierarchically – something seen as far back as the Ancient Greek philosophers – rather than perceiving the planning and planting of settlements, rural and urban, as a continuum; this compartmentalization makes it easier to manage research projects, including the present one, and analyze data, but we must always keep in mind that it creates an artificial and imperfect representation of historical reality.

Part of the challenge for historians, as regards the process of urbanization in England, is that the terms villa or villata were applied by medieval clerks somewhat indiscriminately to villages, towns, townships, and settlements in-between; villata was perhaps more likely to be used for something perceived as more than a village, though less than a borough. There has been a tendency to render such terms, in published translations of national records, as 'town', but they should not be thought of as necessarily implying enough urban attributes to warrant that translation. Some historians have preferred translations such as 'vill' or 'township', but these have problems of their own, such as differentiation from parish as an administrative unit. What these terms refer to are settlements: sometimes dispersed clusters of habitation – occasionally (where actual units of settlement in a particular territory were too small to fulfill administrative responsibilities) of artificial creation, but often a nucleus of population flanked by outlying hamlets. These could have either a rural or urban character (the historical dividing line still being hazy), but generally lacked the privileges and jurisdictional independence of boroughs, though they might be headed in that direction, and the territory designated as a vill could incorporate a borough as one of its components; they did not have their own courts, being part of some larger unit (e.g. hundred, manor, franchise) that exercised judicial jurisdiction, yet were administrative units for certain purposes, such as taxation, military service, and law enforcement through frankpledge and inquisitions – so that, besides the seigneurial bailiff, they also tended to have one or two constables appointed from the community. Occasionally, introduction of a burghal component was part of a broader scheme of village re-organization and/or repurposing of an under-utilized or unprofitable area of manorial demesne – a phenomenon more widespread than is generally recognized. Some of these multi-faceted settlements crossed over into the category of villa mercatoria – townships possessed of markets – some of which were considered important enough in 1275 to receive summonses to parliament.

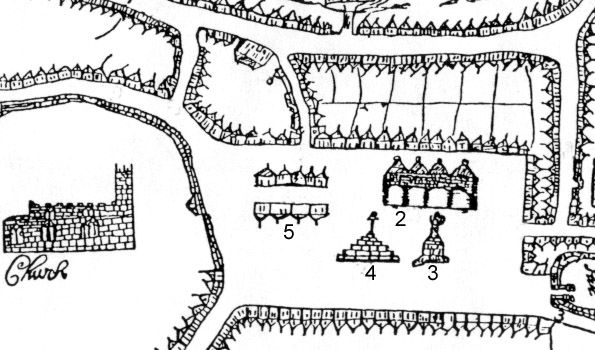

Cawood, in the North Riding of Yorkshire, provides an interesting example of a polyfocal settlement whose various units were the result of planning initiatives of probably different periods during the late eleventh and twelfth centuries [see N. Blood and C. Taylor, "Cawood: An Archiepiscopal Landscape" Yorkshire Archaeological Journal vol.62 (1994) pp. 083-102 the authors acknowledge that some of their conclusions are somewhat speculative]. Cawood was a village within Sherburn, a large pe-Conquest estate of the Archbishops of York, an area bounded by the river Aire on the south, the confluence of the rivers Wharfe and Ouse on the north and by a Roman road connecting Tadcaster (market licence 1271) and Castleton (market documented 1311) on its west side; the Ouse (which provided water transport to York) formed one boundary of Cawood. about a mile from the confluence point, and a road between Sherburn and York crossed the Ouse by ferry at Cawood. Sherburn was the original location of the episcopal residence, but a move to Cawood began at uncertain date (before 1181), and a substantial palace was built there, although Sherburn remained the site of deer park and hunting-lodge. The bishop's manor incorporated some two-thirds of Cawood, while the other third was a manor held by a local family which took its name from the village. It was the archbishops, however, who strove to capitalize on the intersection of travel routes and develop Cawood's revenue potential (from trade, rents, ferry service, and fishery rights), as well as its utility in providing not only commercial goods required for the palace but also residential plots for servants working in the palace and its precinct. The oldest area of settlement was probably that in the vicinty of the church, which still incorporates some twelfth-century fabric, having probably undergone some rebuilding as part of the overall seigneurial plan; this neighbourhood – its main feature a row of regular-sized properties along the opposite side of a road (facing the Ouse bank) to the church and with indications of a back lane – was subsequently extended along what is today Water Row, also with a single row of plots ending in a back lane; both units are suggestive of pre-planning. Another road, connecting Cawood with the nearby vill of Wistow, similarly appears to be a planned addition to the former, as does another neighbourhood adjoining the marketplace, which originally (before considerable loss to encroachment) extended to the riverside. It appears that the episcopal plan here was to enhance the role of Cawood as an inland port and market, and in 1223 Archbishop Walter de Gray (who served Henry III's minority government in official capacities) acquired a licence for a Wednesday market for Sherburn, shifted a few years later to Fridays, perhaps in consequence of a successful challenge from Scarborough; later bishops expanded the quayside facilities and had a canal dug to provide water transport between Cawood and Sherburn, in part to ship building stone from quarries at the latter, previously transported by cart at greater expense; the main approach to the palace gatehouse was via a presumed bridge across this dike, near one corner of the marketplace. The medieval market town of Cawood may be understood as the product of phases of deliberate planning and re-planning, in conjunction with the development of the episcopal palace and its grounds, at a period when many village layouts were being improved and new towns created to flesh out the commercial nework in England. Which of those phenomena Cawood exemplifies, however, is uncertain, as we do not hear of burgesses or burgage tenure there.Distinguishing between villages, townships, and towns was of only occasional concern to medieval administrators, such as when Anglo-Saxon legislation attempted to restrict trading to towns – something the Plantagenets would later try to do in Wales – or when, after the Conquest, taxation came to be applied at different rates to urban and rural communities and town representatives started to be invited to attend parliaments. Urban historians can hardly be critical of medieval writers for their failings, however, since our own preoccupation with formulating a definition that differentiates urban and rural settlements assumes there existed a clear-cut division, whereas the reality of the situation seems to have been more of a spectrum. Despite the large number of market-endowed places, across the country, that acquired names such as Newport or Newton, our focus on 'new towns', as opposed to a more inclusive term such as new settlements, risks introducing a modern bias or assumption into the way we think about such settlements. Newton is one of the most common place-names in England. As an illustration of how the name does not indicate that any of its bearers necessarily ever was, nor had hopes of being, more than a village, we may briefly consider Newton-in-Bowland in the Hodder Valley, Lancashire. There is no sign of it in Domesday and the earliest mention is not until the thirteenth century. Even by the close of the Middle Ages it was little more than a group of cottages and focused on a green surrounded by isolated farmhouses. It lay, in a thinly-populated hinterland, on a minor road that probably originated as a track for drovers or farmers to take animals or produce to market – perhaps that of Clitheroe, a day's journey south, for Newton is not known to have had a market of its own; its seigneurs were of modest status unlikely to have had market ambitions, and its economy was purely agrarian. Its nearby crossing of the Hodder was a ford, not upgraded to a bridge until the eighteenth century, and it had no church of its own during the Middle Ages. There is nothing about it that hints at urbanization.

We may be forgiven for sometimes wondering whether the concept of a town (as understood today), as opposed to a borough, had really crystallized in England prior to the Late Middle Ages. It occasionally emerges from the shadows, such as when distinguishing cities from lesser urban places, but there are no English treatises comparable to those of the Ancient Greek philosophers which venture beyond legend or dimly-remembered history to explain the origins of towns, with the possible exception of one isolated and slightly fanciful Latin text discovered in a municipal archive, of uncertain provenance and age (though in a late medieval script), [transcribed by Smirke, " Early Historical Document among the muniments of the Town of Axbridge", Archaeological Journal, vol.23 (1866), pp.224-226]. This, although embodying grains of historical truth, perhaps does more to show insight into the growth of the market network and its association with urbanization. The unknown author – evidently some cleric of the region – who may have been generalizing from the examples of the borough of Axbridge and manor of Cheddar, calls on a local tradition regarding St. Dunstan as well as the relevant section of Domesday Book. He retrospectively argues that, through intentional provision by the Anglo-Saxon witan, boroughs were established within royal demesne manors throughout the realm to supply peripatetic Anglo-Saxon kings and their entourages with victuals during their visits, while villages were fostered in the hinterland of these boroughs to raise the produce and livestock that would become those victuals. Locally-based royal officials managed the process of acquiring the necessaries, implicitly in the same borough markets that they (explicitly) used to dispose of victuals surplus to the king's needs, with the proceeds despatched to the king's treasury.

Yet this document does nothing to differentiate between towns on the basis of scale or character, and we are hard-pressed to imagine that writers were scientific in applying different category labels to towns, or that criteria for distinguishing the categories were applied with consistency by medieval administrators. Bearing in mind the warning of Maitland, echoed by most authors of treatises on medieval English urban history since, that "no general theory will tell the story of every or any particular town" [Domesday Book and Beyond, Cambridge: University Press, 1907, p.173], we might add that no system for differentiating settlements into types will be applicable across the entire course of the Middle Ages, either in terms of validity or of reliability with regard to individual places. For instance, Manchester, having been the site of a Roman castrum and probable Mercian burh, was a manorial village about the time of Domesday (as well as a township incorporating various lesser settlements), had a burgage tenure component planted at some point between the grant of a fair in 1227 and the time when we first hear of its market (1282, though doubtless older), was upgraded to a liber burgus by charter of its lord in 1301, only to be downgraded by a judicial decision of 1359 declaring it not to qualify as a borough but only as a market town, which it remained until restored to borough status in 1838, elevated to city status in 1853, then changed to a county borough in 1889 (though allowed to retain the honorary title of city). Such is the nature of history.

A similar example, further illustrating the complexity of the situation and worth examining, may be seen in another case from the same region: Warrington (Lancs., now Ches.), a village on what was once the Northumbria-Mercia border. The boundary between the two kingdoms was the River Mersey, and Warrington would emerge at the head of its tidal extent; the river was bridged at Warrington before 1285 and probably in the early thirteenth century. Trade had likely followed the route of the river since prehistoric times, and the Romans appreciated the strategic value of the location, their settlement on the south side of the river, near a ford, acquiring an industrial character, supplying the needs of northern military forces; they may have furnished it with port facilities, though archaeology has yet to demonstrate this conclusively. As a crossing-point of the river, the site was well-served by road connections to Chester and other Roman centres in the region. Much later a Saxon burh – one of a chain guarding the border – was erected in the vicinity, its precise location now uncertain. Thanks to the bridging of the Mersey, medieval Warrington was traversed by a major north-south road connecting Shrewsbury with northern towns such as Newcastle-under-Lyme, Preston, and Wigan, while those of the salt wiches to the south and Prescot to the west were reached by other roads. These routes, and particularly the main north-south route's easy passage across the Mersey, encouraged long-distance traders to frequent Warrington, whose marketplace seems to have been at a junction of the through-road and the Prescot road, just beyond one end of the bridge.

Just before the Conquest Warrington had been a royal manor, focus of a large estate. As the principal settlement in a like-named hundred, Warrington may well have been a market centre, with market activities on some site near castle or church; several log-boats found by archaeologists in the adjacent stretch of the Mersey are testimony to river trade in the eleventh century. Domesday shows Saxon settlement on the north side of the river, with a church; nearby, a motte-and-bailey castle – the largest in the county – was constructed by at least the opening of the thirteenth century, to command the routes to the ford, though it may have been preceded by an older manor-house.

Following the Conquest, Lancashire was granted to Roger le Poitevin, a younger son of Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury. Roger le Poitevin enfeoffed Pain de Vilars in Warrington, which later passed, through marriage, to the Boteler family, taking its name from service as butler to twelfth-century Earls of Chester. William le Boteler (ca. 1165-1233) issued a charter creating a borough there, a plan that entailed development of land for residential plots, and the building of the bridge; the street leading to which was originally, and tellingly, known as Newgate (now Bridge Street). The bridge, by carrying a new route connecting northern and southern England, must have stimulated economic and population growth. Warrington's expansion, primarily along Church Street and Bridge Street, was in the area towards the bridge and away from the earlier settlement focus of castle and church. The marketplace of this planned development lay at the west end of Church Street, a stretch known subsequently as Market Gate, at a crossroads with Sankey Street; adjacent streets, named Buttermarket and Horsemarket, suggest that market activities came to extend well beyond the junction north of the bridge: we should envisage a planned expansion of the formal marketplace in the Late Middle Ages.

Although no copy of the Boteler charter has survived, we know of its tenor through allegations made by the burgesses during their legal battle with William's like-named grandson (ca. 1231-1280), whose own developmental initiatives likely included sponsorship of the foundation, at some point in the 1260s, of an Augustinian friary on marginal land somewhat north of the marketplace; the friary is indicative of the growing size and importance of Warrington as well as its urban character, the latter also seen in the occupational diversity recorded there in a survey of 1465. The charter's provisions included instituting burgage tenure, conceding freedom from certain seigneurial impositions (such as market tolls), granting rights to a fishery, and possibly a degree of self-government through control of a court having jurisdiction over the burgesses and burgages, along with revenues from that jurisdiction. Only circumstantial evidence, however, supports speculation that, influenced by the town-founding tradition of the Montgomery family, Warrington was accorded the customs of Breteuil [George Carter, "The Free Borough of Warrington in the Thirteenth Century," Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol.105 (1953) p.28], despite that the burgesses doubtless knew of their application at Preston and Newcastle.

The later William was attempting to backtrack on his grandfather's concessions; he may have desired to regain control of the lost revenue sources – Warrington's subsidy assessment in 1334 showing it prospering and on a par with the free boroughs of Wigan, Lancaster, Preston and Liverpool – or found the burgesses becoming too independent-minded or their court impinging too much on his seigneurial jurisdiction. In 1275 the burgesses – perhaps emboldened by the Botelers moving outside Warrington after the wooden structures of the castle succumbed to fire ca.1260 – took into the king's court their complaints that, contrary to their charter, William the grandson was obstructing operation of their court, that he had re-imposed tolls and other impositions from which burgage tenure had freed them, and that he obliged them to sell their fish catches to him at a price lower than market value. William, whose family was one of the more powerful in Lancashire and who had served as the county's sheriff (1259), knew how to delay proceedings through repeated non-appearances in court, and it is not clear the lawsuit was ever resolved. In the years that followed, the lords of Warrington took steps to bolster their legal position. Having already obtained in 1255 licence for a July fair at Warrington, in 1277 William obtained royal grant of a Friday market and November fair, and in 1285 his successor, yet another William, purchased a licence for a Wednesday market (probably a second market-day, rather than a substitute for the first), an extension to the July fair, and a grant of free warren for his several manors; he also obtained, in 1286, a royal grant of pontage for four years, to finance repairs to the bridge that drew commercial travellers Warrington's way. The licences were shrewd precautions and problems have been anticipated, either from the general climate of investigation in Edward I's early years, or from the incalcitrant burgesses. In 1292 he was summoned into the king's court to answer quo warranto proceedings concerning his claim to market, fair, and other liberties at Warrington and some other of his manors. He was able to defend by producing in court the charters he had received, but the king's attorney then took another tack, accusing that William and his ancestors had operated the market and fair at Warrington many years before the licences were issued – something that a jury inquisition confirmed. We may wonder whether this information had come to the king's ears from Warrington's burgesses, or whether they provided members of the inquisition jury. The matter was left for William and the king to sort out face-to-face, which probably meant he could expect to pay some additional fee to secure his privileges.

But the burgesses took the opportunity of having William in court to renew their complaints against him. In denying the burgesses' right to hold their own court, he challenged them to show that they had a mayor or a common seal, which were at that period starting to become indicators that helped define the existence of a burgess community; this may have been an attempt at obfuscation, but it is conceivable that both parties' claims had some merit and that what was in contention was actually dedicated sessions of the manorial court, held to address matters specific to the burgesses. A jury inquisition on the complaints was forestalled by the burgesses failing to pursue their prosecution. This was evidently because the parties had reached an out-of-court settlement, part of which is documented in a charter issued by William Boteler a few weeks later. Therein he relinquished or imposed limits on a number of seigneurial rights that were presumably a main source of resentment, his concessions including: exemption from toll in Warrington's markets and fairs, no matter where held in the town; the right to use their own measures, so long as conforming to the king's standards; limitation of fines for trespassing strays to compensation for damage they caused to fields or meadows, these to be assessed only by creditable residents; quittance of payment of pannage for pigs that did not forage beyond Warrington; freedom from having to take oaths against their will (this presumably being related to service as jurors or manorial officials); assessment of the amount of manorial court amercements only by free residents of the vill, in full court; abolition of feudal fees related to transfer of tenements; and the exclusive right of the freeholders to choose each year those officials who would administer the assizes of bread and ale [an in-depth but not entirely reliable analysis of the charter terms was attempted by William Beamont, Annals of the Lords of Warrington, Chetham Society, vol.86 (1872), pt.1, pp. 102-13].

These constraints on seigneurial authority did not define a borough, and the charter was careful to avoid using that term, or 'burgesses', in its text; in that sense it was perhaps a retrogressive step for the burgesses, but it remedied specific bones of contention. Nor did it give any acknowledgement of a court through which the burgesses administered their own affairs. Renunciation of such a court must have been part of the burgesses' concessions in the settlement, although this was not specified in writing until 1300, when the free tenants and community of Warrington quitclaimed to William Boteler the "burgess court of Warrington" [A. Ballard and J. Tait, British Borough Charters 1216-1307, Cambridge: University Press, 1923,p.183], and validated the quitclaim by appending their common seal, which they had perhaps had made to bolster their status claims. The reason for the delay between the two known documents of the settlement may have been that the burgesses wanted a waiting period during which the Botelers, who had reneged on the earlier charter, would prove they could live up to the terms of their new charter; we may note that the quitclaim was issued exactly eight years after the seigneurial charter, suggesting a pre-arranged aspect of the settlement.

Whether Warrington's lords continued to respect their charter, after the quitclaim had been handed over, is harder to say. We continue to hear, from time to time, of burgesses and twelvepenny burgages at Warrington, though rights associated with burgage tenure had been undermined somewhat by the settlement and by Boteler's efforts to regain seisin of some of Warrington's burgages, so that they could be re-leased on terms more favourable to him. By the mid-fifteenth century, many residential properties in Warrington, even those flanking the marketplace, were held on terms involving both a higher money rent and limited labour services (mainly at harvest time); burgages (a few ruinous and even more tenantless) are then still well in evidence, but record was also kept of plots that had never been let at burgage and therefore gave the holders no related privileges, and no tenants are referred to as burgesses [William Beamont, ed. Warrington in 1465, as Described in a Contemporary Rent Roll, Chetham Society, vol.17 (1849), passim].

The example of Warrington shows that what constituted a borough in the Middle Ages was not a matter of universal agreement and that the process of urbanization was not irrevocable but could be quite fragile in small towns, particularly when a manorial lord felt his financial interests were better served by attempting to turn back the hands of the clock. Yet at the same time it helps draw a line between chartered free boroughs and quasi-independent market towns where burgage tenure was in effect for some tenants, but their lives were still tied, to a degree, to the manorial system. To the latter, it seems, free market access and removal of constraints on economic self-determination were more important than the legal and institutional freedoms that nurtured the larger and self-governing boroughs.