Introduction

to the history of medieval boroughs

Introduction

to the history of medieval boroughs Introduction

to the history of medieval boroughs

Introduction

to the history of medieval boroughs

|

Problems of definition |

Continuity or creation? |

Wiks, burhs, and ports Planned/planted towns | Growth of self-government | Urban economy | Urban society SOURCES OF OUR KNOWLEDGE | further reading |

| Sources of our knowledge about medieval towns |

written documents | art and literature | cartography, topography, and toponymy | material culture

Our understanding of history is largely determined by what evidence of the past has survived to us, and principally by such of that evidence which is readily available and assimilable; that is, which has been published, analyzed, and interpreted by antiquarians, academics, independent scholars, or (especially in the Internet Age), unschooled members of the public. The process of publication – and I use the term in its broadest sense of communication from individuals to audiences through whatever media – sifts, summarizes, organizes, reconfigures, and speculates about the basic facts; this Web site is no different. It is a complex and highly conjectural process that can give rise to a variety of viewpoints, sometimes widely differing, on the subject-matter. Some areas of historical study are relatively focused, and so it was initially with the history of English towns, when the available evidence was confined to a limited and fairly manageable corpus of original documents produced mainly by or for the central government and from the observations, over the centuries, of local men or travellers; this pushed researchers towards study of constitutional aspects of towns, and encouraged interpretation of the nature of towns in constitutional terms. The nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw considerable efforts to survey, publish and analyze more documents from local archives, with study gradually extending beyond political history into social and economic history.

There was a strong local focus to many of the early studies of towns, sometimes driven by sentiments of civic patriotism or by the desire to show that towns were players in the greater drama of national political history, particularly the evolution of representative democracy; not a few of the earlier historians were one-time local dignitaries, representatives, civic officials, or parish clergy. These civic histories were a parallel strand to the county histories that antiquarians had long been engaged in producing. Comparative or compilatory studies, drawing information from multiple locations in order to write about urban development in general, or some cross-cutting theme applicable to towns generally, were rarer, but not entirely absent. To an extent it might be said that the study of urban history in England developed out of this interest in local history, though there were other influences – not least a growing appreciation of towns as a significant institution in the revival of 'civilized' society during the centuries that following the seeming near-collapse during the so-called Dark Ages, and of the increasingly urban character of modern society. But it was not until the mid-twentieth century that urban history emerged as a discipline in its own right, interested more in the social and economic than in the political dimensions. It was in the same period that urban archaeology started to come into its own. More recently there has been emphasis on literary studies, art history, statistical analysis, and geographical science as avenues through which we can understand the medieval town and formulate typologies of towns, while trends such as gender studies are also shaping much of the contemporary scholarly output relevant to urban society in the Middle Ages. Today urban history is necessarily an area of interdisciplinary studies, although much of the pioneering work of archival research remains a significant part of the foundation of our knowledge. And so that is an appropriate place to begin an overview of the sources from which our knowledge derives.

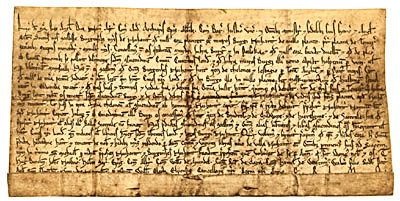

Medieval records, especially local records, compared to those of more recent centuries, tend to be either one-off products or incomplete, even fragmentary, components of what were once fuller series. The majority also are biased towards both administrative functions or preoccupations and a particular segment of urban society: the wealthier townsmen, whose existence and activities are far better attested and documented than those of their poorer neighbours; thus, for example, customs accounts, property deeds, wills, and even most records of civil courts cast a spotlight on activities involving the deployment of wealth. Despite losses from negligence, disasters, and thievery, England is quite fortunate in what has survived, while even losses are compensated for somewhat through notes or even transcripts made by antiquarians. Some towns now have almost nothing from the Middle Ages, but others remain relatively rich in their medieval archives. Yet it is not exclusively to the towns themselves we need look for documentary evidence.

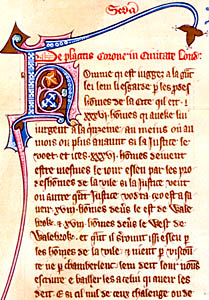

Nonetheless, it is self-evident that for the study of towns, collectively and (particularly) individually, records generated locally are, where they still exist, of pre-eminent value, in that we might reasonably expect them to reflect a local perspective on urban communities, their needs, concerns, and interests. This despite the fact that the great majority of such records were, directly or indirectly, a by-product of responsibilities and functions of agencies that played administrative roles within a community: notably, gilds, courts, and democratic assemblies. The archival history of boroughs thus largely reflects development of self-governing institutions within a community. Indeed there is little indication from within urban society of any habitual record-keeping (as opposed to ad hoc experiments) or high value placed on written records prior to the opening of the thirteenth century, when the emergence of borough self-government (among other factors) provided an impetus to the growth of lay literacy, the need for trans-generational evidence of privileges, assets, judicial transactions, and communal decisions, and the evolution of the office of a professional town clerk. One of the earliest preoccupations of community leaders was to define and identify precisely who shared in the benefits and obligations of such a community, and so membership lists – and very occasionally taxation lists – were compiled.

Since much of the administrative autonomy was initially based on the delegation of judicial jurisdiction and/or recognition of local legal customs, court rolls represent another form of early borough record, dealing mainly with civil disputes, market offences, public nuisances, and minor assaults (though coroners' inquests gave rise to records relating to homicides and felonies). Borough courts were often wide-ranging administrative institutions and their rolls could be, or become, catch-alls for additional types of records; privileges inherent in burgage tenure naturally made court sessions appropriate occasions for public declarations related to property transfers and so, in some towns, court rolls came to include registrations of transfers, mainly in the form of transcripts or abstracts of deeds, quitclaims, and wills. It was also quickly realized that, rather than relying on human memory, it was desirable to make a written record of the local customs governing offences subject to the courts, as well as intricacies of legal procedure; a number of these custumals survive to us.

Those towns unable to wrest from their overlords much judicial independence relied on gilds or public assemblies as tools for self-administration, and the proceedings of such meetings represent an alternate vehicle for the written record; in almost all of at least the larger towns, the assembly – often slimmed down to what were effectively council meetings – became increasingly the focal administrative mechanism and the main source of borough records that preserve evidence of expanding administrative activity, such as the election or appointment of officials, memoranda of renderings of account by some of those officials, formulation or amendment of local by-laws and regulations, non-judicial measures to discipline erring citizens, the provision of public services, and diplomatic correspondence resulting from relations with other authorities and communities. Practice varied much from town to town: for example, in some places assembly records were appended to, or blended with, the court rolls, while a city as large, powerful, and administratively complex as London has left us with numerous series of records from the different institutions of local government.

Financial records represent another large category, stemming from the need of local government both to assure the annual payment of its fee farm and to finance the growing number and variety of activities necessary to protect borough interests and reputation, assure public health and safety, develop and maintain the urban infrastructure, and pay the salaried administrative personnel. This gave rise to records such as accounts of revenues and expenditures, lists of tolls payable on merchandize, and property rentals; but other classes of records, such as membership lists (and records of new admissions) as well as court rolls also had a strong financial dimension; the information they contain about receipts due or paid may have been an important reason for the creation and maintenance of such records. To some students of history these kinds of record may seem mundane (and so they are), but they are closely associated with civil communities. That the most ancient written records are bureaucratic may be more than simply chance survival. For verbal language itself likely evolved not as an enabler of human communication, but as a refinement of communication aimed at improving the capacity for conceptualization, categorization, manipulation, and control of the world; that is, as a tool for planning and collaborative development – capabilities fundamental to the emergence of civilization.

The same observation about a 'dual personality' might be made of town-related records produced by higher authorities– mostly the royal government (and so found primarily among the collections of the Public Record Office, now part of England's National Archives); this duality can be seen from at least the time of the Domesday Book, long the subject of debate as to whether it was intended as a survey of estates over which the king had dominion or of revenues he could expect to receive from the same. These national records both supplement and complement local ones. They include, among the classes most heavily used by urban historians: the charters by which the king delegated administrative autonomy to towns; judicial records of criminal cases tried both locally and centrally; royal investigations into the conduct of local administration; lists of urban assessments for taxes granted by parliament; accounts of customs levied on maritime commerce; and evidence of the many areas in which royal and borough government intersected, in the form of public announcements and private messages which have been a mainstay of historians through the published calendars of, respectively, Patent Rolls and Close Rolls. That last category of enrolled communications helps us understand how the central government viewed the towns and townspeople, though some of their contents occasionally reflect the words or views of borough authorities or even individual citizens.

Most such national documents involve record of some payment to the king, or the upholding, protection, or delegation of royal rights in which Crown assets were implicated. Less easy to explain are the quite large numbers of urban property deeds that have ended up in the National Archives, probably for a variety of reasons, such as that the properties were involved in legal disputes adjudicated by royal agencies, or the Crown may have acquired an interest in them, or simply that they came by a circuitous route through private collections. Modest numbers of original or enrolled deeds can be found in archives at all levels. Beyond the Public Record Office, the collection of the former Department of Manuscripts of the British Museum (now part of the British Library) and that of Oxford University's Bodleian Library are particularly notable for including numerous documents originally belonging to the corporations or citizens of towns, but which fell into the hands of private collectors in an age when corporations had little interest in old documents without day-to-day practical use and were casual about lending them out or pursuing their return; borough records have occasionally turned up in rather unlikely places, but it is hard to generalize about whether this dispersion helped or hindered the preservation of evidence of medieval towns. It seems likely that surviving records from the earliest period of borough self-government represent only a small part of what was actually produced, although both clerical and archival procedures gradually systematized.

A longer tradition of record-keeping than is found in towns existed within the Church, as the original monopolist of literacy, and in the royal government to which it furnished trained scribes and learned administrators. Church records can therefore be another source of information about towns, particularly those that came under ecclesiastical lordship. Episcopal registers provide needle-in-a-haystack research opportunities, though sometimes incorporate pertinent documents. More consistently useful are cartularies into which were copied deeds granting properties to monastic institutions, and the registers into which were copied wills and testaments receiving probate in diocesan Consistory courts, archdeaconry courts, or the Prerogative courts of Canterbury and York. Nor should we forget that chronicles were predominantly the product of members of ecclesiastical institutions, though the attention they give to towns tends to be for the most part superficial; this written genre was only slowly, and in scattered instances, adopted by medieval laymen interested in local history. Similarly, detailed descriptions of particular cities, which are much rarer, are the product of churchmen and filtered through their world-view.

Setting aside wills and deeds, medieval documents created by or (more commonly) for private persons or private use are relatively uncommon, notwithstanding the gradual spread of lay literacy. It is hard to know how much this is due to lack of preservation outside of formal archival contexts, but the number of books and manuscripts mentioned in testamentary bequests, commissioning of compilations of select public records, and the growth of schools, the legal profession, and the book trade, are among reasons to suspect that vernacular composition of memoranda or messages may have been within the capability of quite a few within the wealthier stratum of urban society towards the close of the Middle Ages. We may suspect that developing business practices would have given rise to record-keeping but little has survived, and certainly nothing to compare to the extensive business records of Italian merchant Francesco Datini – which however is an exception even for Italy and itself the result of a chance survival. The account book of London merchant Gilbert Maghfeld for the 1390s is today almost unique, but was surely not so in its own time.

More intimate documents are similarly scarcer now than they likely were once: Margery Kempe's partly autobiographical 'book' is quite exceptional in a number of regards, and correspondence between family or acquaintances stems more from the gentry (e.g. the Pastons and Stonors) than from townspeople, although the Cely Papers pertain to a mercantile family that had business premises in London – their noteworthiness itself being a comment on the want of such documentation. The Cely Papers and Maghfeld's account book owe their survival in part to having ended up in the Public Record Office, while the survival of the Kempe manuscript is perhaps even more fortuitous. Kempe's text bridges the genres of historical chronicle and creative literature; of the latter more will be said below. Despite the dearth of private archives related to medieval townspeople, the richness of some borough archives, augmented by the wide range of documentation surviving from national government sources, has made it possible to reconstruct fairly detailed biographies of a number of townsmen – to which the History of Parliament project is the most eloquent testimony – and even a few women. Prosopography, in which certain subsets of townspeople are studied collectively, has also proven a viable approach in the case of urban history.

The Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, set up in 1869, published surveys of the historical records of a small number of cities and towns, often incorporating extracts; their reports helped spur on further studies utilizing some of those records and remain of some use even today, although certain of the records they describe have since been published more fully. Several of the researchers employed by the Commission, such as Henry Harrod, John Cordy Jeaffreson, Henry Thomas Riley, and William Dunn Macray had published (or would subsequently) catalogues or transcripts of the manuscript records of particular towns. At that period there was a good deal of enthusiasm, on the part of urban corporations, local history and scholarly societies – almost every county has had its own record series – and, often under the auspices of borough authorities, individual historians for publishing medieval records in their original language; the series issued by the Early English Text Society, Selden Society, and Surtees Society, for instance, have included a number of volumes of town records, while the London and Southampton Record Societies, and the Oxford Historical Society have been even more focused on documents pertinent to urban history. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries impressive work was done by some of the great names in local or urban history – Stevenson, Cox, Hudson, Bateson, Harris, Salter, to name but a few – paving the way for landmark studies of medieval towns in general, such as those of Green, Gross, Ballard, Stephenson, and Tait. This focus on issuing transcripts of original records has all but ground to a halt today, given the unfavourable economics of print publishing and the virtual disappearance of Latin from the educational curriculum; the current trend is to publish English translations of primary sources. Large amounts of primary materials remain unpublished (and therefore at risk, notwithstanding today's improved archival practices and facilities), including some very important documents.

|

|

|

Royal charters and local custumals were the foundations of borough self-government. |

|

The term 'medieval studies' gradually came into vogue over the course of the twentieth century to distinguish a multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approach to the Middle Ages from traditional historical studies reliant on archival documents; in particular (but by no means exclusively) it tends to look at works of literature, philosophy, and the fine arts as windows onto medieval society or the medieval mind. The use of such types of evidence initially aroused much concern within the orthodox mainstream on the grounds that works of art and literature are governed by their own conventions and have their own purposes and perspectives quite different from those of administrative or legalistic documentation; they are usually not intended to be literal reflections of the realities of life, but are prone to presenting stereotypes or generalized portrayals, distorting the real world in order to more effectively convey moral or ideological messages. However, if such sources are used cautiously and with awareness of their historical context, they can still provide insight into how concerns and issues of medieval society were perceived by at least some of its members (whether the creators or the intended audience), and indeed may be seen as tools that were helping shape, solidify, or reshape attitudes and perceptions.

During the Middle Ages the vast majority of what we would consider artworks (including products of fine crafts) focused on religious themes, and were mostly commissioned for ecclesiastical settings: stone carvings, roof bosses, altarpieces, wall paintings, illuminated manuscripts, stained glass, misericords, church plate and communion vessels, tomb effigies and brasses. They usually shed only a tangential light on urban society and allowance has to be made for stylization and generalization. In the Late Middle Ages artwork began to infiltrate secular settings, such as town halls, gild halls, and even houses of wealthier townsmen, in the form of tapestries, but practically none survive and textual references to them are undetailed. Illustrated books were work-intensive luxury items, often produced outside England, whose decorations and/or miniatures tend to reflect the preoccupations or interests of the churchmen or nobles who commissioned them; depictions even of Biblical scenes are sometimes set in architectural or domestic contexts familiar to the medieval artists, but may just as easily be copied from some older or foreign source rather than represent elements contemporary with the manuscript. Townspeople or urban culture received scant attention, and even landscapes were uncommon – whereas from illustrations of continental books, we have a relatively large number of depictions of mostly idealized towns, usually their exteriors. Occupational pursuits or recreational activities are more (though not very) common, but their variety is limited by those Biblical texts being illustrated, so in the secular sphere it tends to be agricultural labourers, spinsters, or musicians that we encounter. Maps – which would have been perceived as artistic renderings more than technical drawings – were rarely produced in forms intended for wide dissemination or for preservation.

Medieval England is not noted for its artistic achievement, in comparison to works produced in, say, Italy, France, Flanders, or Germany. It boasts no Lorenzetti, Fouquet, Bening, or Breughel who can provide glimpses into the everyday lives or settings of town-dwellers; nor is it the source of any series of depictions of urban history, occupations, or ideologies quite so remarkable as the stained glass at Chartres, the Sienese tavolette della Biccherna, the popularized editions of the Tacuinum Sanitatis, the illustrated translations of Jacopo da Cessole's De Ludo Scachorum, the House Book of Mendelschen Zwölfbrüderstiftung or the Augsburg Monatsbilder. Of the few manuscript miniaturists and stained glass artists identifiable by name or by style as active in England, many appear to have been immigrants trained abroad, such as Michiel van der Borch, suspected illustrator of works that include the Egerton Genesis and Fitzwarin Psalter, who migrated in the 1340s from Flanders to Norwich, where was already established a community of his Flemish compatriots engaged in weaving. Nor was there much scope for artistic creativity or licence in commissioned products, since the subject and approach of the ornamental elements were often specified in advance by the commissioner, or they might simply be copied from older models; illuminators, like carvers in stone or wood as well as like the master masons we would today consider architects, were then thought of as craftsmen rather than artists. A handful of illustrated books produced in England, such as the famous Luttrell Psalter, give some attention to secular life, though are more rural than urban in their focus. These extraordinary creations tend to get a lot of mileage, in terms of the repeated use of their illustrations by historians, and much reliance has to be placed on illustrations created in countries other than England. A modest number of isolated English artworks are also of interest to the urban historian, such as those in Ricart's Kalendar.

By contrast, the field of medieval English literary studies – encompassing genres such as poetry, drama, biography, romances, fables and legends (some disguised as history), as well as works of allegory, mysticism or philosophy, some of which take poetic form – has proven quite fertile, not only for dedicated students but for historians generally, who increasingly call on literary references to support the evidence of pragmatic documents. Urban Tigner Holmes' Daily Living in the Twelfth Century and D.W. Robertson's Chaucer's London are classic examples of how such sources can be exploited. A further class of written works that has occasionally been mined is of manuals, treatises, and other texts produced for educational purposes. Some of those few medieval authors who have been identified passed significant parts of their lives in urban settings, the obvious example being Chaucer– study of whose works has generated virtually a discipline of its own – but also Kempe, Lydgate, Hoccleve, FitzStephen, Fitz Thedmar and Usk. While these types of textual source have their own particular challenges, in terms of determining either their reliability or their validity for the general population, they do provide colourful examples of everyday life, of attitudes, and values not to be found in official documents, and are particularly useful in giving glimpses of groups less well represented in official documents, such as women and the poor.

As already noted, maps or graphic depictions of English towns are very rare from Middle Ages; indeed, medieval maps of any kind are scarce, relative to the vast volume produced in our own time. Even the concept of geography, as a field of study, is not much in evidence, and was ill-defined, in that period. The maps that have survived to us may represent only the tip of an iceberg; yet, even if so, there is no indication of any habit of map-making, little if any evidence of a sense of the utility of maps as general reference tools, and (outside of Italy) no systematic efforts at mapping multiple locations using standardized criteria. The isolated initiatives to draw maps (or plans) seem to have been conceived less as scientific than as artistic renderings, often incorporating imaginative or symbolic elements; other graphic depictions of towns – very few of which appear in works produced in England – tend also to be sight-unseen generalizations based on features known or imagined as characteristically urban – the rendering of Canterbury shown above being a possible exception.

The very few local maps we encounter – most from the Late Middle Ages – were evidently produced for specific and restricted purposes. Urban planning projects, such as that at Winchelsea could have benefited from the production of at least some simple conceptual sketching of topographical relationships between the main elements of a planned town; but if this realization dawned on the planners and any such sketches were produced, they are likely to have been envisaged working tools with a short-term purpose, not warranting their preservation; the same may be said of the building plans occasionally mentioned in major construction contracts. By contrast, textual documentation – e.g. property surveys, rentals, official statements of urban boundaries, and laudatory descriptions (sometimes categorized as encomia) – was a widely accepted approach to describing geographical areas.

The consequence of this dearth is that medieval historians instead rely on plans, views, or maps from sixteenth to early nineteenth centuries, before much of the urban landscape was significantly altered by redevelopment. Earlier depictions – notably the series created by Speed and by Hogenberg – are somewhat generalized, but nonetheless useful and certainly well used by those studying the larger towns of the Late Middle Ages. In later, professionally drawn, maps – above all the large-scale Ordnance Survey maps of the second half of the nineteenth century – we can still discover the lines of medieval streets and property boundaries; although these sources must be interpreted with caution, the main features of most towns had still by that period changed relatively little from their medieval condition and even the town walls, which were often demolished to improve circulation of intensifying urban traffic, have tended to leave traces in the landscape.

Historians can also resort to contemporary in situ townscapes in an effort to re-imagine the medieval version; to some extent street patterns, open spaces, waterways, major military and ecclesiastical structures are vestiges of town features present in the later Middle Ages. Decay of the fabric, changes in lifestyles, tastes and behavioural patterns, and massive redevelopment in the context of industrialization in the nineteenth century and the introduction of new transportation and commercial infrastructures in the twentieth century, have resulted in substantial discontinuities – the loss of much of the medieval landscape. Yet research has revealed a surprising amount of continuity to have survived (e.g. property boundaries, lines of streets), although much of it not easily visible to the untrained eye. The urban landscape has been characterized by G.H. Martin as a palimpsest, a metaphor referring to the mechanical erasure of writing from a parchment manuscript in order to reuse it for new text, though traces of the old may remain, so that a careful observer may be able to perceive parts of the 'lost' text. Observation and analysis of the changing form of towns – topography, street layouts, buildings– on the ground, through property records, and through historical maps, together with an analytical approach (named after its principal exponent, M.R.G. Conzen) that emphasizes distinguishing within the town-plan discrete units representing different phases of development of any given town, has made urban morphology a growing area of historical study, while modern technology has encouraged a move into the areas of digital mapping and virtual reconstructions of medieval townscapes.

Study of the names of towns and cities (toponymy) also provide peepholes on their early history, though not necessarily their origins, as many places had different or variant names over time, some now lost to us. Many of these names originate in the periods of Anglo-Saxon or Scandinavian settlement, although a few contain older components. Some of the more common elements found in (usually the suffix) of such place-names are:

These rules are not hard and fast, however, and historians have to be careful in interpreting names, understanding them in their specific geographical context, and in seeking out the earliest renderings and historical variants; for example, -den can sometimes mean valley, rather than hill, while -ham can refer to a water-meadow; the name York means little etymologically, but earlier names of the place, Eboracum and Jorvik, help us see some of the historical development, while to understand Bristol we have to see its roots in bricg stowe which means a place of assembly by a bridge, and not give too much credence to a foundation legend formulated after the passage of time had obscured or muddied historical facts.

Likewise, the names of districts, streets and lanes, and particular features of the landscape help us understand the characteristics of medieval towns. To take a couple of the more colourful examples, Gropecunt (or Grope, Grape) Lane is a name known from quite a few towns in the Middle Ages (e.g. Oxford, Yarmouth) – though almost without exception renamed in later, more prudish times – and is suggestive of some side-street or back lane, usually not far from the most frequented part of town, where illicit or commercial sexual encounters took place; lanes that had Paradise or Silver in their name may have similar implications, although the latter term might alternatively indicate craft or market activity – at the market town of Thornbury, in Gloucestershire, for example Silver Street was earlier known as Chipping Street, while at Leicester its earlier name was Sheepmarket. At Hereford the proximity of the former Grope Lane to the marketplace reinforces the possibility it was a focus for prostitution. Ratton, or Rotten, Row, also commonly occurs (e.g. Lynn, York) and in most, but not all, cases probably points to a run-down, verminous stretch of housing inhabited by the poor; while usually encountered in more populous towns, examples are known from small towns, such as Thaxted and Nantwich, and even from villages. Toponymy is itself a branch of onomastics, under which also falls the study of the meaning and derivation of surnames. Some surnames can also give us useful information about towns, such as topographical features or occupational activities. Though surnames and their pre-hereditary equivalents, by-names, were primarily intended to facilitate differentiation between individuals – particularly in post-Conquest England, as the common Christian names became increasingly few – they could also be used to indicate relationships, whether familial, with places of origin or current residence, or within social or economic hierarchies; this development, along with a growing population and the increasing reliance on written records for administration of matters such as land tenure and taxation, helps explain why by-names gradually became hereditary (and, consequently, less reliably descriptive).

By combining evidence from cartography, archaeology, topography, and onomastics it is sometimes possible to identify the sites of medieval urban features now absent, such as demolished defences. Just as post-medieval maps and plans can be useful in identifying earlier features of the landscape, so too seventeenth and eighteenth century sketches, and as well as early photographs, preserve for us evidence of medieval houses, town gates, and other structures that have subsequently disappeared.

Little archaeological work of broad scope took place in towns until the Second World War prompted urban redevelopment. This followed a period of rather wanton destruction of the historic fabric of many towns, with little effort to document what was being swept away, when there arose (only partly out of appreciation of the value of heritage to tourism) an awareness of the need to protect historical elements of the urban landscape. The closing decades of the twentieth century saw the emergence of urban archaeology as a discipline in its own right, more widespread and systematic archaeological activity within towns, and the establishment of archaeology units within local government. Major excavations continued to rely to large degree on the limited availability of sites in consequence of urban redevelopment projects and developer funding. In a few cities, such as London, Winchester, Southampton, Ipswich, Norwich, and York, major excavation programmes have done much to elucidate the urban landscape and urban society, particularly of the periods for which written documentation is scant.

Both quantitatively and qualitatively, the best fieldwork has been conducted only during the last half-century, due in part to earlier preoccupation with Roman remains and corresponding lack of interest in the medieval world. There is still, to some extent, a bias towards archaeological investigation of the period earlier than the thirteenth century, for which textual records are scarcer; historians interested in the origins or revival of urban life in England have tended to rely that much more on archaeological evidence. For the Later Middle Ages, the combination of written records and of material remains, whether archaeological or architectural, complement, contrast, and sometimes counter-check or even contradict each other, allowing for a richer yet more balanced understanding, and wherever possible fieldwork is usually accompanied by archival research.

Intrusive investigation (excavation) has increasingly been supplemented or even superseded by non-intrusive methods of study, including aerial surveying of landscapes and systematic recording of above-ground architectural remains, both those visible from the street and those hidden within – for although most domestic facades and interior layouts have naturally been subject to much post-medieval remodelling, there have been quite a few rediscoveries of medieval frameworks, ceiling support structures, or cellars entombed within modernized houses. The growth in public interest and government support for the identification and restoration of heritage buildings is doing much to protect and highlight what now remains, and a handful – notably Barley Hall in York and Dragon Hall in Norwich – have even been turned into interpretive centres to show aspects of life in a medieval town, while a few others have been rescued from destruction to be preserved in open air museums.

For the most part, textual, artistic, and material culture resources speak to different dimensions of medieval urban history, although they can be used in conjunction very effectively, and we must also recognize that artworks and archival documents are artifacts whose physical composition, structure, and design also have something to say about the people or society that produced them. Archaeology has generated important evidence on matters such as on settlement patterns and density, the growth of individual towns, town walls, land uses, industrial and commercial activities, domestic conditions, burial practices, diet and health of town-dwellers. That is, about the urban fabric and its history and about the quality of life of those who lived there. In the process it, along with the discovery of hoards, has brought to light elements of the material culture of urban society, most of it visually unspectacular in comparison to the works of art that are mainly associated with ecclesiastical settings (see above) or the finely crafted possessions of the nobility, yet invaluable in showing us everyday objects, some of which may be mentioned but are rarely described in testaments or inventories and infrequently depicted in medieval art. Nor must we forget to acknowledge experimental archaeology, through which historical insight is sought by attempting to replicate medieval structures, objects, or experiences and using the process and its products to test assumptions or hypotheses.

Objects found by archaeologists tend of course to be those made from more durable materials – metals, ceramics, stone, bone – but perishable materials sometimes survive, at least in part, in the right conditions, and so, across multiple sites, we end up with a wide range of products objectifying various aspects of daily life and medieval culture. Beside fragments of building materials, food remnants and industrial debris, the more common small finds typically uncovered on urban sites are illustrative of domesticity (e.g. mortars, locks and keys, cutlery, vessels for storing, cooking, or serving food,), occupational and other economic activities (grindstones, spindle whorls, tools, commercial weights, fish hooks, construction hardware, imported pottery, seal matrixes), clothing accessories (buckles, clasps, jewellery) and other personal items (mirrors, combs, toys, weaponry), and travel (components of horse harness, spurs, pilgrims' badges – markers of visits to distant shrines). Another common find is coins, numismatics being an ancillary area of urban studies that is particularly useful for the Anglo-Saxon and Norman periods, when towns were the preferred location for minting; the volume of coins identifiable with each mint can be used to suggest a ranking of the larger towns, and changes in relative importance over time.

Objects made of organic materials, such as wood, leather, and cloth, have survived far less well, but there are occasional finds of items such as shoes, portable flasks (of leather), or wooden buckets and spades, for example; many other partially wooden or leather objects can be inferred from remaining metal components. Furniture, furnishings, and clothing once belonging to lay townspeople have rarely – in England, at least – outlasted the wear and tear or the neglect and risks spanning many centuries, though some have chanced to survived when consciously preserved or stored away in a forgotten corner; for evidence of these goods, however, we rely more on artwork.

It is not clear whether medieval townspeople had much sense of material heritage, though they evidently were desirous to pass along certain possessions (such as books, tableware of precious metals, jewellery) to their descendants – though whether because of such objects' utility, socio-economic value, or sentimental attachment of their owners is harder to say; such luxury items represented a form of financial investment. Compared to the inmates of today's consumer society, medieval men and women can be thought less materialistic; yet townspeople came increasingly to share with their betters the desire to display, and if possible exaggerate, their socio-economic status through their costume, ornamentation, and the design and decoration of their homes. Some recent examples of viewing medieval society through the prism of its material history are David Hinton's Gold and Gilt, Pots and Pins: Possessions and people in Medieval Britain (Oxford University Press, 2005), and Ottaway and Rogers' Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Medieval York (Council for British Archaeology, 2003).

As Iain McGilchrist notes: "Every realm of academic endeavour is now subject to an explosion of information that renders those few who can still truly call themselves experts, experts on less and less." [The master and his emissary: The divided brain and the making of the Western world, Yale University Press, 2009, p. 3] Medieval urban history might appear to the novice student a confined area of study, but this is far from true. Today our knowledge of it is expanding increasingly less through the pioneering work of individual researchers and more through collaborative projects undertaken by multi-disciplinary teams from multiple institutions, and occasionally multiple countries, just as, during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, progress owed much to the coordinating or sponsoring initiatives of governments at different levels and of private associations of scholars.

The Historical Manuscripts Commission and scholarly societies have not been the only sources of series pertinent to urban history. That commission's work fed into and was followed by the even more ambitious programme of the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England, inventorying the topographical, archaeological, and architectural built heritage of many counties, with a few volumes dedicated to particular towns and cities. Neither commission was able to complete its work, but their reports remain of much value to historians. Other examples include the Historic Towns series produced in the late nineteenth century under the general editorship of Freeman and Hunt, which aimed to make local histories of the more important towns available to the general public, while the more substantial Victoria County History series (productive in a slightly sputtering fashion throughout the twentieth century and still continuing its mammoth task today) incorporates more scholarly accounts of the history of numerous towns. One of the VCH contributors, Mary Lobel, went on to oversee the Atlas of Historic Towns series, which combined detailed maps of English towns, as they were in the past, with accounts of their development over time by combining documentary, archaeological, cartographic and topographic information; its work covered a dozen cities before there was a hiatus, but the Historic Towns Trust is now active in producing further volumes and maps. More recently English Heritage's Extensive Urban Survey programme has generated a large number of reports – mostly on smaller towns (predominantly in southern and western counties) not previously paid much attention – that combine archaeological, topographical and documentary information to produce summaries of historical development; but this too seems to have faltered, in the economic downturn, short of its mark, whilst the products from an Intensive Urban Survey programme (looking at 35 cities and larger towns and initially taking the form of archaeological databases) have not, insofar as completed at all, been made widely available.

For much of the twentieth century the majority of urban studies dealt with specific individual towns (and those mostly the larger ones), largely in isolation, for it is a challenging enough task to examine and analyze the primary documentation relating to a single town, in cases where the town has a well-preserved archive. There is today, however, a greater trend to view them in the context of their regions, the nation, or even comparatively with continental cities. Some make the assumption that common problems tend to call forth common solutions. Given the gaps in evidence for indvidual towns, a comparative approach can provide helpful insights. But it runs the risk of focusing unduly on similarities (or presumed similarities) between towns, at the expense of understanding the significance of differences or unique circumstances.

Some of our information is second-hand; that is, it comes not from the original documents, but from copies, extracts or summaries of them made by antiquarians. Even though we must read the interpretations of antiquarians with caution, their number included some very learned persons, and today's urban historian owes them a great debt, particularly in cases where they have recorded transcripts of, or notes on, documents whose the originals are now lost to us. The unscientific work of amateur archaeologists can similarly be useful, in the absence of better information. All information, however, whatever its source, is unavoidably coloured by the world-view, preoccupations, or agenda of the author or interpreter.

The various sources of our knowledge, briefly reviewed above, can be used in conjunction and/or provide us with a means of testing each other – seeking confirmation or contradiction. Some sources crystallize information at one point in time (e.g. maps, surnames), and do not reveal change. The latter requires a series of snapshots, such as archaeological layers, maps of different periods, or record series such as financial accounts or court rolls. Understanding and visualizing the medieval urban landscape and society is both science and art. It involves data processing, detective work, wisdom, and imagination. The availability of remote sensing and spatial technologies has, in recent years, provided new vistas for topographers, cartographers, and archaeologists, while digital media have opened new avenues for the dissemination of images, transcripts, or translations of textual records.

In the final resort though, it is hard to paint a confident picture of medieval English townsmen or townswomen. Documents intended to express personal feelings, hopes, desires, ambitions etc. being rather scarce, human emotions, values, and attitudes have largely to be extracted with much caution from literature (that dealing with courtly love, for instance, being a very imperfect reflection of reality), or inferred from documentary sources not intended to record such matters: such as, for example, from normative literature (texts stating how people should conduct their lives and affairs), or from legal records (evidencing how people have acted contrary to public, or at least governmental, expectations). Working within such constraints and with limited sources of evidence is the lot of all who study medieval history; we seek to know our ancestors through the marks they have made on the world, the fingerprints they have left on time: that is, their voices frozen in ink, perceptions of their environment mediated through art, their material works, the landscapes they inhabited, the technologies, techniques, strategies and rituals they applied to living life, individually and communally.

previous |

main menu |

next |

| Created: January 2, 2013. Last update: June 19, 2021 | © Stephen Alsford, 2013-2021 |