A mostly rural county in south-western England, Wiltshire is best known today as a landscape peppered with ancient monuments which bear testimony to the presence, since at least the Mesolithic (though the most famous monuments are Neolithic), of settled and well-organized societies which established strongholds and communal settlements on the hills and high chalk downland – cut into by a number of river valleys, some wide, some narrow – that characterize the region. In the northern part of the county the heavy and poorly-drained clay soil of the valleys had woodland and other pasture that would come to support large numbers of sheep for dairy farming and cheese production, whilst in downland areas the well-drained soil, so long as well-manured (another product of sheep), was good for arable agriculture even before mouldboard ploughs came into widespread use across England. From a later, but still prehistoric, period settlement expanded as forested areas were cleared for farmland, except on steep valley slopes where arable agriculture was difficult; widespread trade is evidenced, and tribes formed as territorial groups. More germane to the theme of this study than the ancient monuments are the number of large estates owned by the king in medieval Wiltshire, for it is within a number of these that we discover markets.

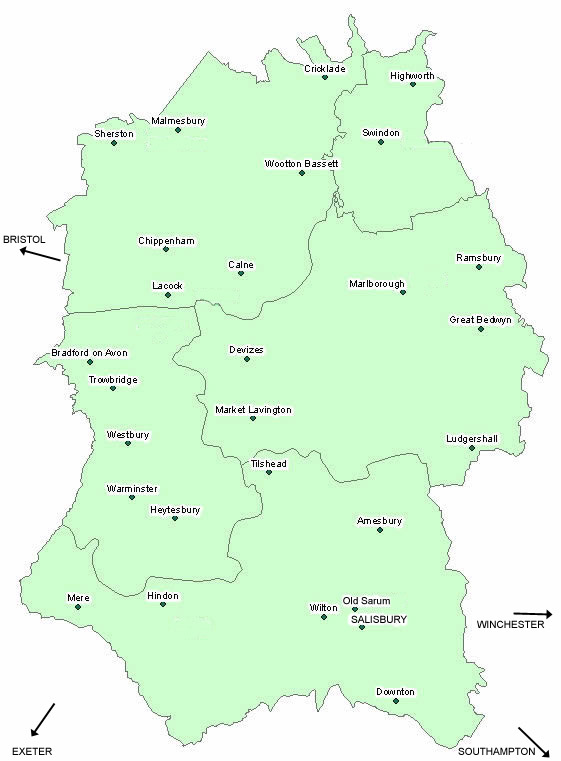

At early date the main routes of communication across southern England, and into East Anglia, took shape, such as the Ridgeway and the Icknield Way, crossing Wiltshire by means of high ground, along with numerous minor trackways. After the Romans conquered the region, they continued to use those routes, and to erect villas alongside them, but added their own, more direct, roads (even though some stretches remain conjectural), with London as the main focal point, but also with places like Mildenhall and Old Sarum – which would later be the sites of royal markets – as key junctions within what would become Wiltshire; for example, one road via Old Sarum connected London and Exeter. The Saxons in their turn continued to use the prehistoric routes and Roman roads, but also introduced new roads, many of only local significance, connecting neighbouring settlements, but others running further, through the valleys along the banks of rivers; they perceived roads as links between towns, used to carry travellers to market or on other business errands; a special royal peace came to be seen as applicable to major routes (e.g. the Foss Way, Ermine Street), which were partly Roman in origin, and the concept of the king's highway emerged. There was a reciprocal developmental influence between the route of the principal (commerce-carrying) roads and the siting of fords, bridges, and market settlements. The famous Gough Map – drawn up in an era when travelling commerce, particularly in wool and cloth, had contributed to the identification of major routes – depicts a well-developed road system across medieval England, with two of the principal roads from London crossing Wiltshire: one via Winchester and Salisbury to Exeter, the other through Marlborough and Chippenham to Bristol. There must also have been, by the late thirteenth century, adequate road connections between Salisbury and the major port at Southampton, to service long-distance traders and their packhorses.

Though not short of rivers, landlocked Wiltshire had only a few with stretches that were navigable for cargo-carrying barges, at least during parts of the Middle Ages; the erection of water-mills and weirs brought about the same obstructive problems here as in the better-watered counties along the east coast. The Thames passed through Wiltshire, but this was one of its less navigable stretches; though it has been speculated that Cricklade, situated at a crossing-point, might have served as a port for Roman Cirencester, it is uncertain whether river navigation would have supported that, though there are occasional instances of barges carrying goods to Cricklade in the post-medieval period. The Bristol Avon was probably navigable up to the early thirteenth century in its tidal reaches, from the river Severn to the Severn estuary at Avonmouth and thereby into Bristol's harbour, although the narrow and wandering route of the Avon Gorge made that part tricky for navigation; only smaller boats could get as far as Bath, or beyond to other communities serviced, such as Chippenham, Lacock, Melksham, and Sherston. The Hampshire Avon, which actually rises in, and is mostly within, Wiltshire, serviced market sites at Upavon, Amesbury. Salisbury (in whose vicinity it was joined by tributaries the Nadder, Wylye, and Bourne, which connected to the sheep-farming villages of the plains), Downton, and Fordingbridge before continuing to Christchurch (Dorset), to empty into the English Channel; again parts were navigable at times. We should bear in mind, however, that rivers were important not just for commercial transport; at Bradford, Calne and Chippenham, for example, rivers provided a natural defence and water-source that encouraged settlement and fuelled industrial activities in various ways.

It has been argued [Michael Costen and Nicholas Costen, "Trade and Exchange in Anglo-Saxon Wessex, c ad 600–780", Medieval Archaeology, vol. 60 (2016), p.3] that finds of seventh- and eighth-century coins suggest a lively and partly international commerce taking place through much of Wessex in that period, emanating from the coast and spreading up into Wiltshire, which is landlocked. Though these finds are scattered and, cumulatively, not extremely numerous – stemming from assumed losses, rather than hoards – they include clusters in or around Salisbury and Wilton and on the road between Old Sarum and Winchester, while others may indicate a route across Wiltshire, connecting Mercia with Berkshire and northern Hampshire, perhaps associated with the salt trade. A concentration in the part of the county between Warminster and Westbury, an area under royal control, might reflect a collection point for wool, the Costens speculate [Ibid., p.22], but the scattered nature of most of the finds suggest to them a widespread commerce, not reliant on any one central redistribution point but with trade routes controlled to an extent by Wessex kings through toll sites and outlets for the surplus produce of royal estates.

Legend has the invading Saxon groups establishing the kingdom of Wessex following a victory over the Romano-Britons at Old Sarum in 552, which enabled them to spread through Salisbury Plain. The future Wiltshire marked, in the next century, the western edge of Saxon domination, with Christianization underway – the first monastic houses were established, probably in the seventh century and with royal sponsorship, at places that included Bradford-on-Avon and Malmesbury, and were joined in later centuries by nunneries at Wilton and Amesbury and numbers of small churches servicing individual, mostly private, estates, as the older system of great estates and minster territories fragmented, helping give rise to the plethora of manors and parishes that became features of the post-Conquest landscape. Despite Wessex falling at least partly under the hegemony of Mercia, the ninth century saw a reversal in the relationship, expansion of Wessex into the south-west and south-east, campaigns against the Welsh, and the organization of Wessex into shires as its territory expanded, although the last may have taken place as early as the eighth – this remaining a matter of some scholarly debate [reviewed by Simon Draper, Landscape, settlement and society: Wiltshire in the first millennium AD, Durham University PhD thesis, 2004, vol.1, pp.102-03].

Wiltshire most probably acquired its name from Wilton, which was essentially the capital of Wessex and would be the county town during the Middle Ages. It featured a number of large multi-vill estates (which would later become caputs of hundreds), most still in royal hands at the time of Domesday, though a few had been granted to bishops or religious houses; they also tend to be associated with minster churches. The caput, or villa regalis of such an estate – of which an echo survives in streets named Kingsbury in a few Wiltshire towns – was the centre for estate administration, both secular and ecclesiastical (i.e. hundred and parochial) while secondary, or dependent, settlements had the task of furnishing the provisions that supported the estate's centre and general population. Although the early existence of such estates, along with their manner of formation, is debated – Draper [op. cit., p.188] argues that by the later Middle Saxon period proximity to a river crossing, or a natural spring, or a marsh-surrounded hill (as opposed to less viable marginal locations) appear key topographic determinants in the stabilization of nucleated, and perhaps even planned, settlements around royal vills or minster churches, and often the two in combination – Domesday seems to see them as significant; in Wiltshire they are practically all evidenced, post-Domesday, as locations of markets, and even those not identified in Domesday as boroughs may be suspected of having been proto-urban. In the time of Aethelstan (924-27) mints are known to have existed at Old Sarum, Malmesbury, Wilton, Cricklade, and Marlborough, with Great Bedwyn joining the list later; most of these had begun as royal estate centres. Although the Viking invasions would push Wessex to the brink of extinction, a resurgence led to the formation of England under the Wessex royal house, an association re-established under Harold Godwinson after the later Danish invasions, which included devastating assaults on Wilton and Salisbury.

The redistribution of estates following the Conquest placed almost half the county in the hands of ecclesiastical institutions, and about one-fifth remained in possession of the Crown. The new Norman elite continued the practices of its predecessors in building churches and founding monasteries, though the latter never became exceptionally numerous, and few beyond those already mentioned above were of more than local significance. Wiltshire's economy remained almost entirely based on agriculture and its derivatives: Domesday reports large numbers of mills, the production of wool for domestic use and export was a major occupation, and by the fourteenth century several towns had become notable centres of cloth manufacture. The county's inland location, bordered only by other counties, made it relatively secure, so that castle-towns are far less of a phenomenon here than in the Welsh Marches, and most castles put up in Wiltshire lost their military value relatively quickly, being mostly ruinous today. At the time of Domesday large areas were still forested and the county remained relatively lightly populated; clearing forest for farmland had made slow progress particularly where the terrain was unfavourable, and some of these areas where the Crown owned much of the land, such as in the vicinity of Chippenham and Melksham, would be designated royal forest at uncertain date (though by Norman kings, who would also import from Normandy ideas about a system of forest administration).

By the time of the Poll Tax (1377), Wiltshire's relative ranking, in terms of population, had not changed, but in terms of taxable wealth it was ranked much higher, this change attributable to good farmland, production of wool, and participation in the general growth of the cloth industry. The wool trade in Wiltshire was highly organized by the time it starts to be documented, in the early thirteenth century; very large flocks of sheep are evidenced on a number of manorial demesnes, and even at the lower end of the landholding hierarchy the cumulative number of sheep was large, perhaps because many peasants hoped that proceeds from sale of wool might enable them to purchase freedom from villeinage or to expand their landholding. Cheese-making too was a growing industry in fourteenth-century Wiltshire.

Maitland described Wiltshire and Dorset as "the classical land of small boroughs" [Domesday Book and Beyond, Cambridge: University Press, 1907, p.175]; though since his time we have come to appreciate how prevalent small towns were in most counties, Maitland was of course thinking of the eleventh century. We must also understand from Maitland's observation that there was a lack of large towns in Wiltshire. Prior to the late arrival of New Salisbury, towns of the first rank were instead in surrounding counties: Winchester, Southampton, Bath, Gloucester, Bristol, Oxford. Yet a number of estates were held by high-ranking dignitaries, secular and ecclesiastical, to whose interest in developing their revenue generation potential may be attributable evidence for markets or large-scale industrial activity at or near several estate centres, although Wiltshire mints do not seem to have been very productive.

Five towns are known in Wiltshire from the Romano-British period, but none had continuity, and present-day towns can mostly trace their antecedents to Saxon villages or burhs. On the other hand, the dispersed settlement that characterized Roman organization of the rural areas remained a prominent feature during the medieval period. Continuity of settlement, from the Romano-British period to the Middle Ages, was likeliest to occur near river crossings or springs and on ground raised slightly above surrounding marsh. Apart from during the danger period of the Scandinavian invasions, the Saxons preferred lower-lying sites, such as in valleys, often previously occupied only lightly or not at all, to the hill-forts of the pre-Roman communities; low-lying areas were less exposed to the wind, had better access to water, and were closer to soil suitable for farming. However, promontories were sometimes chosen as settlement sites, as offering a mix of natural defence, and ready access to watercourses and communication routes. That Wiltshire was already relatively well-urbanized by the Conquest meant that fewer of its towns were planted on virgin soil by the Normans – New Salisbury being an exception of some importance.

Domesday acknowledges only Wilton, the county town, and Malmesbury as boroughs, but in a number of other places the presence of burgesses or the right of the king to the 'third penny' of revenues hints at a different story. While these may have been indicators of borough status in an age when the term 'borough' was not closely defined, in the Late Middle Ages the term acquired more technical definition, so that a place (such as Manchester) with burgesses and burgages might be accorded by the courts the status of market town, yet denied that of borough. However, our concern here is primarily with an earlier period. While early monasteries attracted settlements that gradually became urban, notably Wilton and Malmesbury, more of the county's towns took form, prior to the Conquest, as burhs. The close grouping of Wilton, Old Sarum and Salisbury suggests a dispersed urban function, with the hill-fort of Sarum serving for royal residence, Salisbury as the location of a minster church, and Wilton as the collection point for taxes. Cricklade had also developed clear urban features before the Conquest. Several royal manors developed an urban character after the time of Domesday: Amesbury, Bedwyn, Calne, Chippenham, Tilshead, Warminster, and Westbury. Being a royal manor was of course not a guaranteed route to urbanization; Melksham for instance never, during the Middle Ages, progressed beyond the status of manorial market. Similarly there are quite a few places in Wiltshire whose names incorporate elements derived from 'burh', but not all went on to become towns. Tilshead on the other hand, is perhaps more symptomatic of the economic development of Wiltshire as a whole, since it reflects the growth of sheep farming in the Late Saxon period, an activity that necessitated points for collection and redistribution, both of wool and of the animals themselves, something that also helps explain Marlborough's importance.

By the time of the hundredal enquiries of the mid-thirteenth century the Crown had granted away over two-thirds of the 38 hundreds of Wiltshire, once in royal hands; the alienated hundreds were about evenly divided between the ecclesiastical and lay tenants. It is unsurprising to find the bishops of Salisbury as major players in the urban development of the county. Richard le Poer (bishop 1102-39, though prevented from coming into office until 1107) in particular is found associated with a number of Wiltshire towns (Devizes, Malmesbury, Marlborough, Old Sarum). A Norman priest whose early career saw him acting as steward for William of Normandy's youngest son, Henry, the latter upon becoming king appointed Roger as first his chancellor then (in effect, if not in name) his justiciar, before promoting him to the bishopric, after which Roger continued to act as Henry's first minister and as regent during his absences abroad. Though not an especially learned ecclesiastic, he was a very capable bureaucrat with an exceptional understanding of financial administration, introducing a system of accounts auditing that became the Exchequer, and also a prodigious builder. His abilities were matched by the power he accumulated and the growth of concern about his ambitions, and would eventually lead to his downfall when King Stephen came to fear he placed self-interest before loyalty. Richard Poore (bishop 1217-25)) is not known to be related to Roger, despite their common surname, but he followed in similar footsteps, in that he combined royal service with his episcopal duties, though he was educated (at Paris) and came to a less disastrous end. He was the founder of several markets and planner of New Salisbury. Episcopal towns perhaps had an advantage over those under secular seigneurs, in that bishops' duties meant they were more often on hand to provide the king with guidance and support, rather than travelling around to different estates in various counties or being overseas on military service; this support could be important when inter-urban trade disputes arose, particularly if the bishop had influence at the king's court.

Most settlements in Wiltshire that would later be considered towns were already established by 1100 and had some features associated with the definition of 'urban'; perhaps the majority had developed from what were royal estate centres by the Middle Saxon period. By the close of the thirteenth century there were around sixty places that might be considered towns, if we apply only the criterion of the presence of a market. The importance of sheep farming in the county does much to explain how Wiltshire could support so many; there was a need for collecting centres and events through which wool and pells could be more conveniently acquired by the merchants who would ship much of it overseas, a commerce that was a key foundation of the growth of the English economy in the Middle Ages. The wool trade stimulated the development of the native cloth-making industry, initially to meet local needs but by the time of Edward III to fuel increasing exports, and this in turn stimulated even greater efforts in wool production and organization of the wool trade. Wiltshire at first contributed mainly a coarse cloth, known as burel, to this trade, but subsequently expanded into products of middling quality. Fulling mills are documented in the county at around the same time they appeared elsewhere in England. Salisbury was the major centre within the county for both manufacture and marketing of cloth; taxation data from 1334 shows it contributing almost as much as all the other taxation boroughs of the county combined, while the 1377 tax data indicates a population larger than the total in all other Wiltshire boroughs; it well outclassed the ancient capital of Wilton.

By the close of the Middle Ages more centres of the cloth industry had emerged – though not all can be considered urban – such as Bradford-on-Avon, Devizes, Trowbridge, Westbury, and Castle Coombe. The last's prospects took a leap forward in the early fifteenth century, thanks in large part to the seigneurial policies of Sir John Fastolf, who obtained control of the estate through his marriage. He renewed a market and fair licence originally obtained by Lord Badlesmere in 1315, purchased for his tenants, some of whom were clothiers, royal privileges that freed them from certain financial obligations, provided housing for cloth workers who wished to relocate to Castle Combe, had two new fulling mills built, and for over two decades spent large sums on locally-made cloth as uniforms for the troops he raised for the war in France; this boom did not outlast his death, when his late wife's family resumed control of the estate.