Introduction to the history of medieval

boroughs

Introduction to the history of medieval

boroughs Introduction to the history of medieval

boroughs

Introduction to the history of medieval

boroughs

| The urban economy |

The purpose of townsmen in pursuing self-government was not some abstract philosophy of liberty or self-determination. Its principal thrust was towards creating conditions favouring entrepreneurial endeavour (or, on the other side of the coin, removing obstacles inhibiting such endeavour). First and foremost towns are entities within the economic fabric. This has led some historians to define towns primarily according to economic characteristics:

|

|

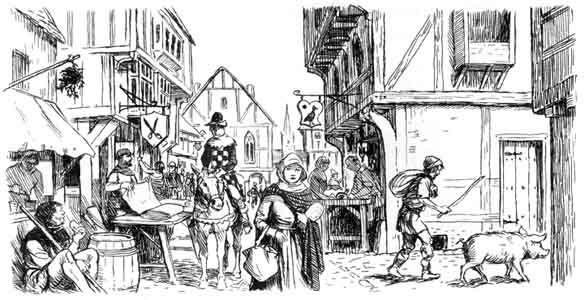

A 20th-century artist's depiction of a street scene from a 14th century English town, illustrating the retailing of goods – such as cloth or (far left) cooked foods – from stalls outside of houses, the ground-floor interior being used rather for the production of goods. On the left-hand side a tavern is indicated by the alestake projecting from above the awning. A reminder that agriculture still had a place in many medieval towns, however, is the ever-troublesome pig. |

The first of the above criteria assumes a dedicated market site at which trading is regularized, including occurring at regular and frequent intervals, rather than ad hoc situations governed by whenever travelling merchants appear on the doorstep (e.g. the early wiks), or the larger-scale commerce at fairs held once a year; the muddy area is settlements that, aside from a regular market, did not possess other characteristics considered urban. It was in southern England particularly that a network of small market centres initially prospered; only later did many fall before the competition of large towns centralizing trade.

The second and third criteria help historians distinguish towns from villages, where the community, for the most part, produced its own means of subsistence – those villagers not directly involved in agriculture undertaking supportive roles (e.g. blacksmith) – and where the villagers, or villeins, were obliged to devote part of their time and energy working the demesne land of, or performing other duties for, their manorial lord, and had limited freedom of action or movement. We know that many of the residents of towns engaged in agriculture to some degree – the common fields and pastures that are features of most towns are one piece of evidence; this was in part to furnish their own larders but also to supply the businesses of themselves or others – such as commerce in victuals, brewing and baking, or operating taverns and cook-shops. It will be noted that the definition does not require that a majority of the townspeople be in non-agricultural occupations, but nor does it try to specify what proportion might be considered significant. The numbers are less important that the fact of what is referred to as "occupational heterogeneity", that is, townsmen earning their living through a variety of activities, including agriculture, land-holding (i.e. income from rents), commerce, crafts and industry, and administrative and other professional services. The original "bourgeoisie" was not necessarily a mercantile class. Medieval townsmen in fact tended to be multi-occupational; although many had a primary source of income, they also had side-activities that earned them money.

The popular image of medieval towns (insofar as there is one!) tends to be of the industrial centres of Flanders or the great mercantile cities of Italy. In England, only London was within that kind of scale; its key location enabled it to maintain throughout the Middle Ages a leading role in commerce, even when long-distance trade was at a low ebb. However, it was not so dominant as to overpower other English towns, particularly those on the coast or with good river connections to the sea. Nonetheless, the fortunes of individual towns fluctuated with changing economic circumstances and growing competition. The coastal town Yarmouth, for instance, for a while in the fourteenth century became more prosperous than larger and otherwise more important rival Norwich; but Norwich's more central location and access to both road and river transportation routes made it more adaptable in weathering hard times, whereas Yarmouth's reliance on the sea and particularly the fishery left it vulnerable to a variety of setbacks. The competitive environment could provoke sometimes bitter struggles to suppress neighbouring markets, as in the cases of Norwich vs. Yarmouth, Yarmouth vs. Lowestoft, Ipswich vs. Harwich, and Maldon vs. Heybridge.

Coastal ports, such as Lynn and Yarmouth, between them had the lion's share of long-distance (whether international or coastal) trade; the involvement of their burgesses in agriculture was correspondingly lower. The residents of inland towns were, by contrast, more involved in both the production and the re-distribution of local and regional materials (notably foodstuffs and wool); their markets and fairs were some of the channels through which that produce was routed to export towns, although the prosperity of these towns probably relied more on purely regional trade. At the same time, the wide range of crafts usually present in towns meant that the local economy was not overly dependent on imports. As magnets for itinerant commerce, towns inevitably played a key role in the collection of tolls and customs.

England's wool was its single most important export, shipped abroad for making into cloth which the English then bought back. As townsmen involved in the wool trade became aware of the economic folly of this – particularly as the king sought to obtain a greater cut from the wool trade through export customs and wool taxes – they invested in developing a local cloth-making industry, beginning in the twelfth century but more intensively in the Late Middle Ages. In most towns where this happened, the industry eclipsed even the leather-making trades that were very important to medieval society. A large number of townspeople were employed in one aspect or other of the cloth industry. Both industry and trade underwent fluctuations during the Late Middle Ages, varying so considerably from place to place that any generalization is difficult; the cloth industry in particular locations might be affected by factors such as competition from lesser towns or from rural areas (as well as from the continental cloth-making centres), technological changes, the growth of craft gilds and corresponding attempts by urban authorities to suppress or control them, as well as more general problems such as changes in trade routes, both locally and internationally, or the silting of local harbours.

|

Drawing based on a English manuscript illustration of ca.1400, touching upon aspects of the economic system. In the foreground a packhorse, loaded with merchandize, is driven towards an inn (with welcoming hostess); a network of inns across the country was important for commerce. The building at lower right, with hanging sign indicating it some kind of commercial or industrial establishment, may represent a craft workshop that produced some of the goods being transported by the horse. At rear right, the artist has depicted a walled town, location of major marketplaces for goods, while at left stands a castle or fortifed manor-house – residence of aristocracy who were consumers of luxury goods imported by merchants. The packhorse reflects the role of land-based transportation in the economy, while the ships and boats represent the importance of water transportation. |

Economic fortunes were equally tied up with the political and social troubles of late medieval England. The population expansion and opening up of new farmland that contributed to urban prosperity in the tenth and eleventh centuries had now reached its limits; there was no more good agricultural land to bring under the plough, and in fact the ecological and competitive balances had swung in the opposite direction to start a process of environmental degradation. Together with adverse climatic conditions, the result was a number of bad harvests and famines in the first half of the fourteenth century. An atmosphere of social malaise and economic instability was created, thanks to factors such as:

Similar instability abroad, both economic and political, affecting markets for English goods, also had a part to play.

In this atmosphere some towns declined while others did fairly well – the situation is so complex that historians still do not understand it well. Although townspeople's standard of living seems to have improved, many urban governments were complaining of a troubled local economy and financial difficulty in meeting public obligations (such as the maintenance of town walls or payment of the fee farm). That difficulty may have been partly a consequence of reduction in the local tax base after the plague, yet a growth in public services and other responsibilities of local government that put ever greater demand on the municipal budget. Nor should we ignore that what represented hard times to some townsmen, meant opportunity for others; plague, for instance, purged the ranks of the urban merchant class and created openings for new men, while armies at war provided good business for some craftsmen and merchants such as victuallers of York, while a select number of merchants were beneficiaries of royal favouritism or illicit profits from customs administration.

Despite the difficulty with generalizing when individual towns' fortunes varied so considerably, on the whole the Late Middle Ages was not a period of further urban growth. Far fewer new towns were created, existing towns did not grow much beyond their established boundaries, while in some the populated areas shrank(e.g. Winchelsea). But many towns – particularly those well-established and with diversified economies – were resilient enough to either weather the storm or to prosper at the expense of smaller towns or market centres, some of which went under. This ebb and flow of fortune, whether of individuals or collectives, is of course fundamental to the way we conceive and perceive history; as the 'father of history', Herodotus, felt able to conclude (and Plato subsequently to develop into a more sweeping thesis) from traditions about the preceding age:

"the cities which were formerly great have most of them become insignificant; and such as are at present powerful, were weak in the olden time.... human happiness never continues long in one stay."

previous |

main menu |

next |

| Created: April 5, 1999. Last update: January 6, 2018 | © Stephen Alsford, 1999-2018 |